“I thought the British accepted election results”.

This comment, made to me last year, unprompted, by a Lebanese friend (Hi, Aamir!) I hadn’t seen for 20 years did two things. First, it focused my mind even more intently — if that were possible — on the job of covering Brexit for various outlets. Secondly, it alarmed me. “In my part of the world,” he continued, “when people don’t accept election results, well, then there is war”.

“This is Britain,” I said limply. “We don’t do that anymore”. Meanwhile, 400,000 marched through the streets because they wanted to reverse the 2016 EU Referendum. “That,” he said — pointing out the window at a throng of people with loudhailers, face paint, EU flags, and a spirit of general bonhomie — “does not look like acceptance. And it does not look British”.

My father made a related observation while watching footage of Lady Diana’s funeral: “Those people do not look British. What happened to the British?”

Before you leap to conclusions, miss, and break your neck, this was not a comment on immigration or diversity in either case. Both Lady Di’s funeral and the big People’s Vote marches were, like Extinction Rebellion protests, whiter than my Dad’s native Aberdeenshire. It was a reflection on national character, which appeared to be retreating from the emotional restraint that Britons developed in response to the religious “enthusiasm” of the Civil War.

Political historian Stephen Davies — perhaps fortuitously — started his career as a specialist in the Early Modern period, and this scholarly background gives his new book, The Economics and Politics of Brexit: The Realignment of British Public Life additional salience. He gets why at least some people in the world’s oldest democracy with the first recognisably modern party system (around since 1671) now behave like Aamir’s compatriots. I sent him a copy of the book and he said he had to ensure he read it without a pencil in hand or he would end up “underlining every sentence”.

Davies developed the political realignment thesis one sees everywhere these days, and it’s unfortunate he often isn’t credited for it. Long before the likes of Rob Ford, Eric Kaufmann, or Matthew Goodwin appeared, Davies was warning that technocratic, expert governance was “politically exhausted” and what gets called “the global rules-based order” is about to pass its use-by date, let alone its sell-by date.

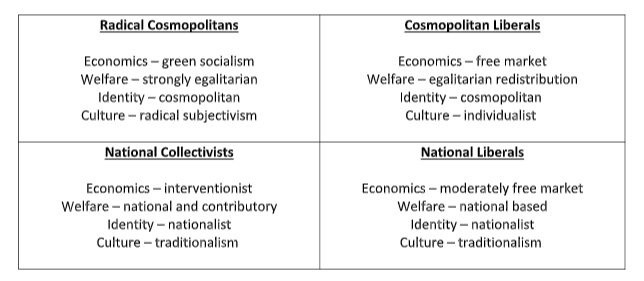

Brexit, Davies argues, was a catalyst for the realignment now nearly complete. As in chemistry, it speeded up the reaction without itself being consumed by it. “The question is not so much that of social conservatism versus social liberalism,” he says. “Instead the key issue is that of identity, and in particular the tension between globalism and cosmopolitanism on one hand and nationalism and ethnic or cultural particularism on the other”. In parallel, economics has become a second-order concern.

Key to grasping this insight is that Brexit is a consequence of the realignment, not its cause. Davies is a materialist. This means divisions of opinion across society are not only or even primarily a matter of what the great and the good believe and are not derived from popular culture but emerge instead out of real conflicts of interest and everyday life experience. He does not think “politics is downstream from culture”, or — to the extent that it is — this happens only when those purporting to represent majorities do not adequately exercise their power.

He is adamant that the UK electorate is both more right-wing and more left-wing — if one draws on the old alignment — than widely realised. Large majorities support Tory policies on restricting immigration, funding defence, and “Laura Norder” while being socially conservative on the newest rights campaign — transgender issues. The 2017 iteration of “Corbynomics”, meanwhile — renationalising rail, putting workers on company boards, and redistribution “from the few to the many” — is popular. A political party that combined what Goodwin calls “national populism” with (mild) Corbynomics would make bank.

Davies documents how survey after survey shows a large majority of the (pre-December 2019) British electorate agreeing with the statement “Parliament does not represent or listen to people like me”, and that this is particularly acute among those inhabiting the bottom left quadrant in his realigned version of the famous “political compass” diagram.

It was National Collectivists who left Labour between 2005 and 2019, finally doing so in sufficient numbers last December to collapse the “Red Wall”. The party to which they lent their votes, meanwhile, had rapidly planted itself in the National Liberal corner. “The history of the Conservative Party means this should not have been a surprise to anyone,” Davies observes drily.

In its long and successful existence, it has had many ideologies and positions and has shown great willingness to change and discard these as the occasion requires. The core principle that has persisted is simply that there are many things in life more important than politics and therefore the scope of politics should be restricted. To that end, the main goal of the party has always been to win elections and hold power, no matter what. Holding office is an end in itself, because it keeps the other lot (who do want to use politics to change the world) out of office and stops them doing things”. [p 204]

This ideological flexibility meant they were able to scoop up large numbers of Cosmopolitan Liberals as well — those who voted Remain but find socialist economics and “woke” identity politics deeply irritating. That said, Davies also points out that it’s easier to unite the nationalists in the bottom half of his political compass than it is to unite the cosmopolitans in the top half.

Anyone with eyes can see the extremity with which Wokies persecute liberal leftists and centrists, sometimes accompanied by even grimmer nastiness than is directed at Tories. Given the form cultural traditionalism takes in the UK — it doesn’t revolve around issues like abortion, gun laws, or same-sex marriage, for example — it’s also harder to accuse Nationalists here of bigotry or racism and make the claim stick. They want immigration controlled at the national level. Very few of them want it stopped altogether. They’re cool with gay marriage. They just don’t want trans women playing women’s rugby.

Like my friend Aamir, Davies is critical of the behaviour from Remain “elites”, particularly their willingness to entertain conspiracy theories, turn Parliament into a global laughing stock, and reject election results.

In doing so he takes care to draw a distinction between the great bulk of the 48% who voted Remain and the die-hard People’s Vote types who he estimates (based on polling data) to be about 20% of that number. He makes a compelling case that many Remain voters in both the Radical Cosmopolitan and Liberal Cosmopolitan quadrants simply did not (and do not) know any National Collectivists socially. Their only awareness of such people is what amounts to a thumbnail sketch of Ken Loach’s filmography: “poor wee bastard has to work down pit” to “no pit for poor wee bastard to work down”. He is right to observe that, while this isn’t about to turn the UK into Lebanon, it is seriously unhealthy.

The echoes of the realignment he documents are all around us, reverberating with ever greater intensity thanks to Covid-19, Black Lives Matter protests, and now wrangling over HMGov abrogating the Northern Irish bits of the Withdrawal Agreement. Never mind that what the UK has done is small beans compared to, say, Australia’s wholesale demolition of the 1951 Refugee Convention.

It represents the UK’s first serious assault in decades on the notion that international legal abstractions should override political decisions and the wishes of electoral majorities. Davies suspects the role and power of the judiciary and the human rights legislation beloved of many people in the top left quadrant has a good chance of being the defining issue over the next decade.

The prospect of yet more of these tussles will doubtless fill many people with dread. Mind you, if you’re into ideology, the Great Realignment is like Christmas Morning. UK politics will not lack for excitement or debate.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.