Appearing on the Today programme last week, Radosław Sikorski, a former Polish foreign minister and close political ally of current EU Council President Donald Tusk, said: “The fact is that Britain is 15 per cent of the European Economy. If there is a disruption to 15 per cent of Europe’s trade, they can live with that, whereas for Britain, Europe is 47 per cent of your economy, so the disruption to you will be much greater.”

Sikorski is actually confusing shares of economies with share of exports but his point still stands. In proportional terms, the EU means more to the UK than vice versa. Were the EU and UK to impose trade embargoes on each other, the UK economy would be devastated, while the EU as a whole would fare better (although some EU member states would be affected far more than others).

But Mr Sikorski’s choice of words – “they can live with that” – downplays the huge suffering that a disruption to 15 per cent of Europe’s exports would cause. It is language loaded with intimidation. It is to play politics with people livelihoods. It is, to steal a phrase from Remainers, using people as bargaining chips.

The UK’s Office of National Statistics (ONS) reported in 2016 that exports of UK goods and services to its EU neighbours stood at around £240 billion, while exports from the rest of the EU to the UK were valued at around £310 billion. It seems a fair assumption then that a larger number of EU jobs are reliant on trade with the UK than vice versa. A reduction in trade between the two sides could cause more job losses on the continent; a reduction in tax-takes on the continent; a bigger strain on public services on the continent.

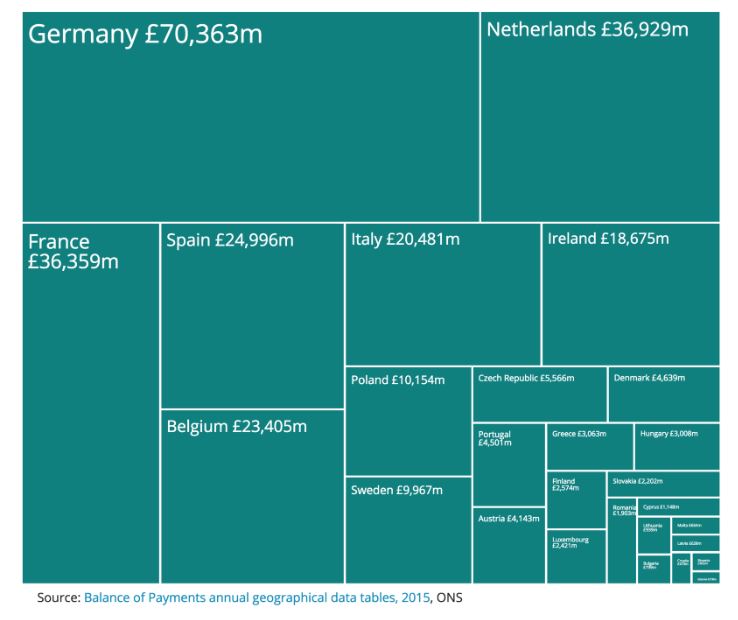

This ONS graphic of where EU trade to the UK in 2015 originated gives a good indication of those in Europe that will suffer most if the EU and UK cannot strike a trade deal by March 2019:

Interestingly, of the six founding members of the EU that enjoy a privileged status in Brussels, five were in the top six exporters to the UK in 2015. It is also worth pointing out that the five largest EU members states were all in the top 8 exporters to the UK in 2015.

This means that the EU’s big guns have the most to lose from a no deal Brexit. And so once negotiations are taken out of the European Commission’s hands and placed back in the Council, under the control of EU member states, reason and pragmatism are likely to trump the more dogmatic approach that currently prevails.

Some have already voiced their grave concerns. Belgium’s economy minister Kris Peeters said on Friday that “The potential impact for our country could well be catastrophic,” adding that “According to our calculations […] Belgium would lose 42,000 jobs, Britain 526,000 and the EU as a whole not less than 1,200,000.”

A recent study by Dutch bank Rabobank found that without a Brexit deal in 2019, every working Dutchman could be as much as £3,500 worse off because of the close trading relationship between the two countries. In a statement issues shortly after the referendum, France’s National Association of Food Industries warned that the consequences of no deal for France’s agricultural industry could be calamitous.

For the EU’s most fervent supporters, however, the priority isn’t the economic sense of a reasonable deal with the UK. Instead they are interested in using Brexit to stamp out Euroscepticism in other member states.

Not only is such a plan irresponsible, it is likely to backfire. Voters are not naive. If it becomes widely understood that leaving the EU need not be detrimental to a country, but that the EU feels it must impose additional arbitrary penalties to cause visible suffering, the case for EU membership starts to look rather flimsy.

If , as has been argued by the pro-EU lobby throughout my life , leaving the EU is such a suicidal decision, why would European leaders feel the need to double-down on the expected suffering? Why would they want to sacrifice their own voters’ jobs just to make the point, badly, that leaving the EU will hurt UK prosperity.

To hear from Brussels that the UK must suffer is very worrying indeed. To hear senior political figures state that the EU can live with the disruption to 15 per cent of its exports is ludicrous. The member states most affected by this reality will never accept such a scenario.

This rhetoric forms part of a drawn out piece of political theatre that was conceived by the EU when it decided, unilaterally, that Brexit negotiations should be split into two. Hopefully it won’t be long until they move on to the only subject that really matters to people’s livelihoods in all this: the post-Brexit trading relationship.

And this – not punishing the UK – is precisely what the EU should also be focusing all its efforts on.