A lot has changed since the snap general election was announced on April 17th. While the Conservative Party started the campaign with a lead of more than 20 points over Labour, some opinion polls now have them with as little as a three percentage point edge.

A landslide victory now looks far from certain, which will be significant and detrimental in terms of the Brexit negotiations.

Especially given the hubris suggested by EU leaders’ public pronouncements when it comes to their negotiating position. For example, Jean-Claude Juncker seems content with the talks failing.

Such pronouncements, if taken at face value, suggest confidence on the EU negotiating side, and perhaps indifference to the outcome of the general election and its consequences for the Brexit negotiations.

Yet there are many reasons to believe that this may be a bluff. The EU faces a series of existential threats that imply significant trouble ahead, potentially weakening their hand in the upcoming negotiations and making it more likely they will seek a reasonable agreement with Britain. A large majority for Theresa May would no doubt make this even more likely.

So, what are the key existential challenges for the EU?

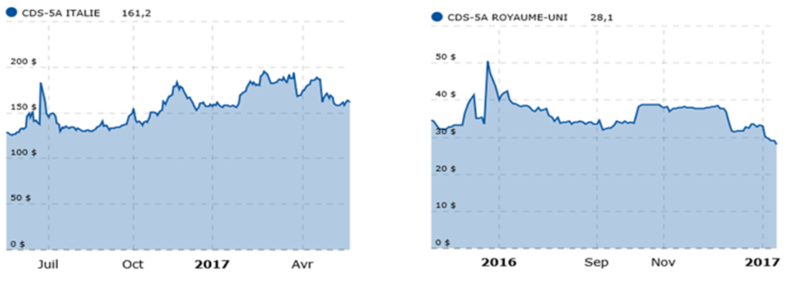

Well, Italy and Greece remain major economic trouble spots. Italy’s debt pile is over 130 per cent of GDP and its GDP per capita has actually fallen over the last 18 years. Its banking system remains precarious, with bank stocks plummeting over the past year. Markets have become increasingly concerned about an Italian sovereign default (incidentally, the opposite is true for the UK).

Left: Italian Credit Default Swaps. Right: UK CDS.

Greece’s fiscal position continues to be unsustainable with a debt to GDP ratio of 180 per cent. And things may even get worse. Around 90 per cent of its fiscal consolidation has come from higher taxes rather than spending restraint, leading to the measures inevitably being recessionary. The thorny issue of debt relief has also yet to be resolved. The IMF is continuing to refuse to put its resources into the bailout agreement, and any further debt relief measures will be a difficult sell to the creditor countries.

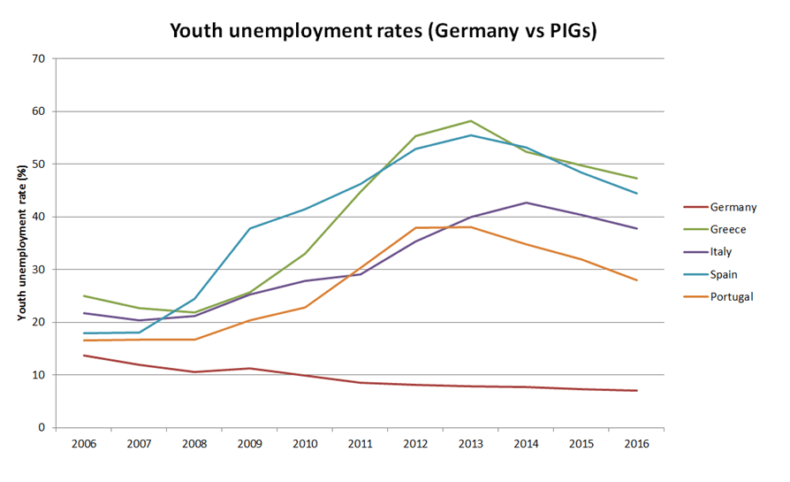

The contradictions of monetary union will also be hard, if not impossible, to solve. According to the European Commission’s own analysis, monetary union has had limitations and downsides in terms of increased unemployment and social hardship in many of the periphery economies. Earlier this year, Mervyn King – former Governor of the Bank of England – perceptively remarked that it is “questionable whether people are willing to tolerate low growth and high unemployment indefinitely”.

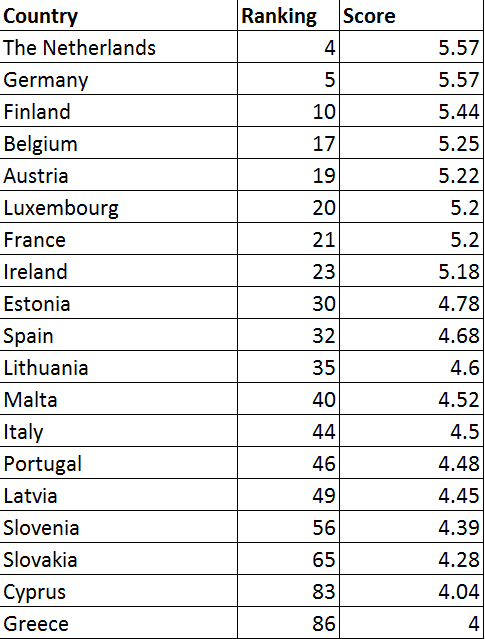

Competitiveness of Eurozone countries (world rankings)

Many argue that a fiscal union is needed to solve the large competitiveness gaps within the Eurozone. The Netherlands is judged as the fourth most competitive country in the world against Greece’s ranking of 86th, for example.

But this proposal is far from a silver bullet. The introduction of Eurobonds, which is effectively a mechanism of pooling economic risk across the Eurozone, has been hugely unpopular in many European countries. Imposing a broader fiscal union would be a difficult pill for the populations of creditor countries to swallow. Furthermore, fiscal union could, in fact, make the Eurozone’s problems worse by simply masking the competitiveness problems of struggling member states.

Public Opinion on Eurobonds

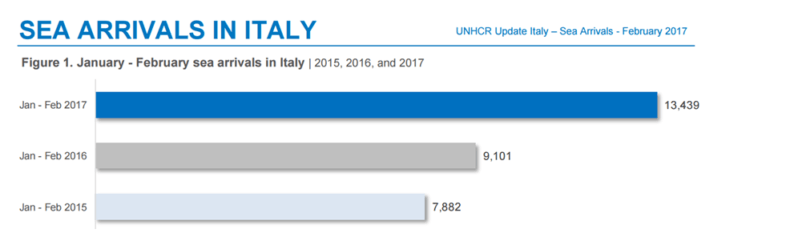

Europe’s external border could also pose challenges over the coming years. The EU-Turkey migrant deal could be at risk, following President Erdogan’s success in the Turkish referendum earlier this year. Moreover, the undocumented arrivals are still continuing at an unprecedented rate into Italy, with arrivals at the beginning of this year being higher than the equivalent figures for 2015 and 2016.

According to Eurobarometer, immigration is now viewed as the largest problem facing the EU and is at its second highest level that has ever been recorded. The “open door” policy pursued by Angela Merkel has, in particular, created enormous tensions with the Visegrad group of countries. Their refusal to accept migrant quotas has led the EU to formally set up infringement proceedings against Hungary and President Emmanuel Macron has previously said that he would seek sanctions against Poland.

Far from Euroscepticism being simply a British phenomenon, all of these factors are leading to an explosion of anti-EU sentiment on the continent. In fact, rising Eurosceptism poses an existential threat to the EU, according to Jyrki Katainen who is poised to become the next European President.

Of course, many might argue that these existential threats will make the EU close ranks and insist on a bad deal for Britain. Indeed, in the short term, senior EU officials and European politicians are likely to take this view, demanding that the so-called “divorce bill” is agreed before post-Brexit trade negotiations can be agreed.

But in the longer term, there is likely to be a realisation that a “no deal” with the UK risks exacerbating the EU’s existential challenges, rather than reducing the risks associated with them. No deal would no doubt have consequences for the EU’s financial stability, lead to a significant rationing of resources and have a huge impact on many of its exporting industries. Some EU countries would also be affected more than others, which in itself could lead to increasing tensions within the bloc.

There has been much scepticism about Britain’s negotiating hand, both in the British press and on the continent. Yet there appears to be far less scrutiny about the EU’s negotiating position, which faces, perhaps, long-term ineradicable existential challenges. The European Commission has currently set out a clear negotiating position, but how well this stands up to its inherent long-term tensions remains to be seen. The opposite is true for the UK Government, which will – in all likelihood – benefit from an increased majority after 8 June.

That is, of course, if Theresa May is successful in achieving this in a week’s time.

This article is based on a Centre for Policy Studies report, “The External Challenges Facing the EU”