In 1999, we were going to colonise Mars, in 2001, we’d be bound for Jupiter, and in 2005, we’d have miners on Mercury. These predictions come from the golden age of science fiction – respectively, Ray Bradbury’s The Martian Chronicles, Kubrick’s 2001 A Space Odyssey and Isaac Asimov’s Runaround – but the future ain’t what it used it be. We’ve made slow progress conquering the stars, and back on earth, we’re facing an identity crisis.

Last week, 21-year-old Brielle Asero hit fame on TikTok for a tearful video about working a 9-5 job. Needless to say, online satirists had a field day, but Brielle – a clever, idealistic graduate – is asking important questions. What’s the point? What is she working towards, what comes next? It’s a story about a lack of a story, and whilst it’s from the US, it strikes a chord in the UK. A July Ipsos Mori poll found that 75% of us thought that Britain was becoming a worse place to live, and ONS polling in 2019 found that 33% of adults thought the country’s best days were behind us. In the ONS study, those that thought the country was on a negative spiral were more likely to report lower personal well-being, which in turn becomes an economic issue because unhappy people are less productive. Brielle is a symptom of a policy problem. By most metrics she’s very privileged – but she doesn’t have a narrative. Saddled with crippling student debt, her link between work and a better tomorrow isn’t clear. Her parents will almost certainly have had better lives than she will.

A glut of policy work has been done on Britain’s sluggish economy – and it looks more like a Vauxhall Astra chugging along in the slow lane than a rocket heading to the moon. But when we look at the countries overtaking Britain, they have something beyond economics in common – and that’s strong narratives. In 2021, India became the world’s fifth largest economy, while Poland is predicted to have better living conditions than the UK by 2030. And while both countries have lower living standards than we do today, teenagers in these growing economies will be better off than that of their parents. And that’s a powerful story.

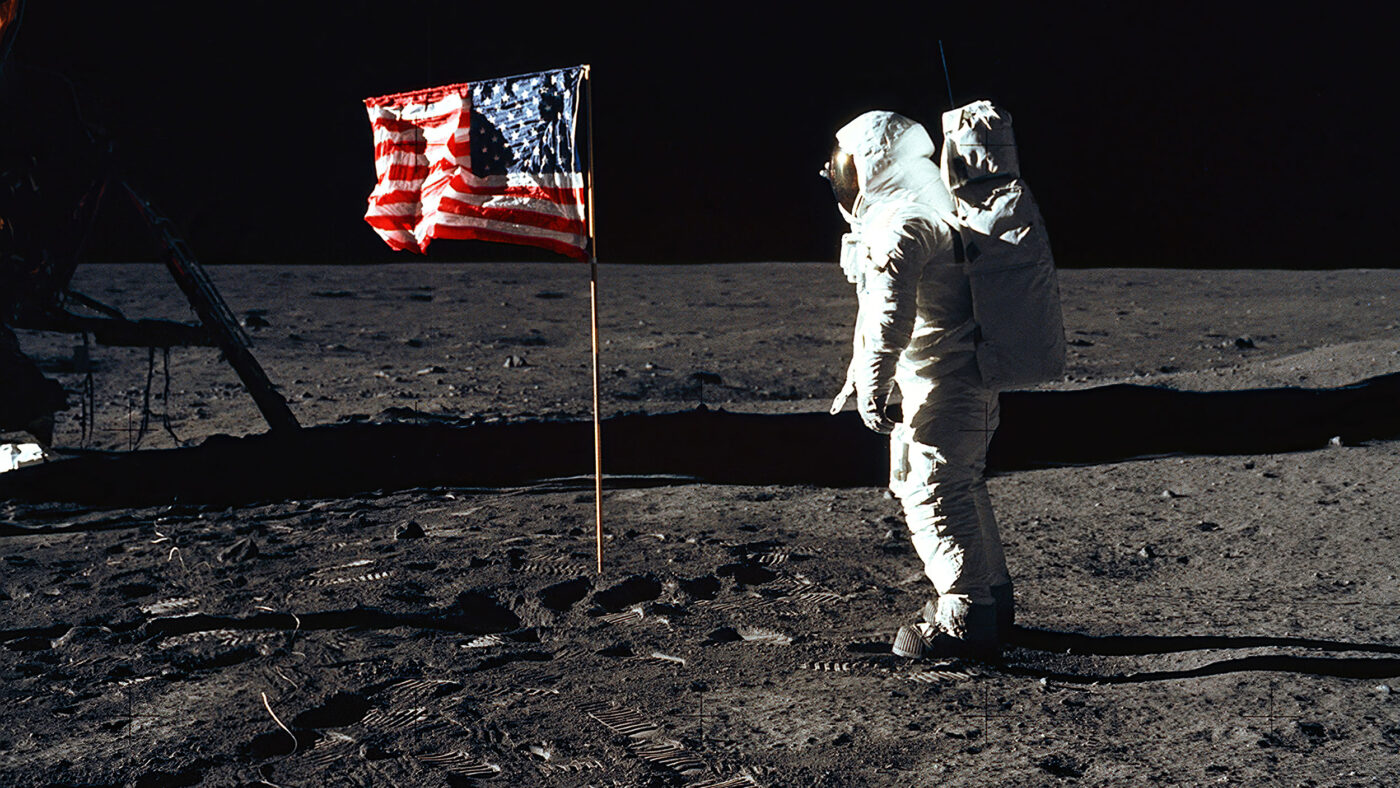

Back in the days of the Space Race, the West had a story. That’s why the writers of the science fiction golden age – who weren’t all optimists – took if for granted that we would conquer the stars. There was a hero – the United States. A villain – the Soviet Union. A conflict – to be the first to reach the moon. And a narrative – democracy or communism, the good guys vs the bad. That narrative taps our primal human instincts: a story of heroes and villains and an opportunity to play a part in it. There’s a story about President Kennedy visiting NASA and meeting a janitor who explained his job as ‘putting a man on the moon’.

It’s a powerful tool for behavioural change, whether organic or artificial. We see it in advertising. Marketing for most non-essential products sells a dream to get you to buy a product. Become fit and confident by buying the new sports shoes; socialise with friends on a summer evening by buying the drink. We see it in politics. The word ‘slogan’ comes to English from Gaelic, a combination of ‘slaugh’ (army) and ‘gaim’ (shout). Translating it literally as ‘war cry’ gives the litmus test for political success. ‘Yes We Can!’, ‘Take Back Control!’, or ‘Make America Great Again!’, could all be shouted by a Highlander charging into battle. These slogans do two things – they offer a dream and they call for the speaker to participate in it. The political campaigns that sell products rather than dreams fail: ‘the strength and experience to make change happen’ (Hillary Clinton) or ‘strong and stable government’ (Theresa May). You can’t imagine the Highlander shouting them, and that’s why they don’t work.

And these narratives don’t just influence behaviour, they buck trends. Party membership has plummeted across Europe since the 1960s, but Jeremy Corbyn made Labour’s membership more than double. In Italy, Beppe Grillo took the Five Star Movement from an online group of ’40 friends’ to 33% of the vote in the 2018 elections. Interviews with Momentum or Five Star supporters previous apolitical people now talking about excitement and hope. They’d never been involved in politics before but Corbyn and Grillo had offered a dream and a war cry: join the underdog and fight to change the world. While neither of these leaders succeeded in taking their parties into power – their underdog narratives failing to survive contact with reality – their careers do demonstrate the capacity of messages to engage people in politics.

We can see that raw power in the story of another comedian – Volodymyr Zelensky, like Grillo, was elected on an anti-establishment ticket. Like Grillo, the underdog narrative didn’t sustain his popularity, and his domestic approval ratings plummeted to 12% once in office. But unlike Grillo, the plot changed again. Russia invaded Ukraine, Zelensky became the hero in the underdog fight once more and his approval ratings shot back up.

However rational we think we are, humans are hard-wired to respond to dreams and belonging, motivated by slogans and stories and symbols. On paper, religious belief has declined in the UK, with ‘no religion’ rising from 15% to 37% in 20 years. But in 2020 the slogan ‘Stay Home, Protect the NHS, Save Live’ leveraged two things: it gave us opportunities to become heroes by saving lives, and made us feel powerful by protecting something sacred (the NHS). Rainbows sprung up across the countryside like roadside shrines and much of the country followed the instruction with religious zeal.

Brielle’s story and recent history demonstrate two things. First, when people face a narrative vacuum even when conditions are good, it impacts happiness. That then damages productivity and creates a downward spiral. The second is that narrative vacuums are detrimental because we’re wired to need stories and symbols. If we can’t find those things, particularly in a time of crisis, we’re likely to turn to the next best thing, such as exalting the NHS to a national religion. However, while they offer policy positions, neither Rishi Sunak or Keir Starmer are providing a gripping, optimistic narrative. Articulating a clear character arc should be a top priority for any government.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.