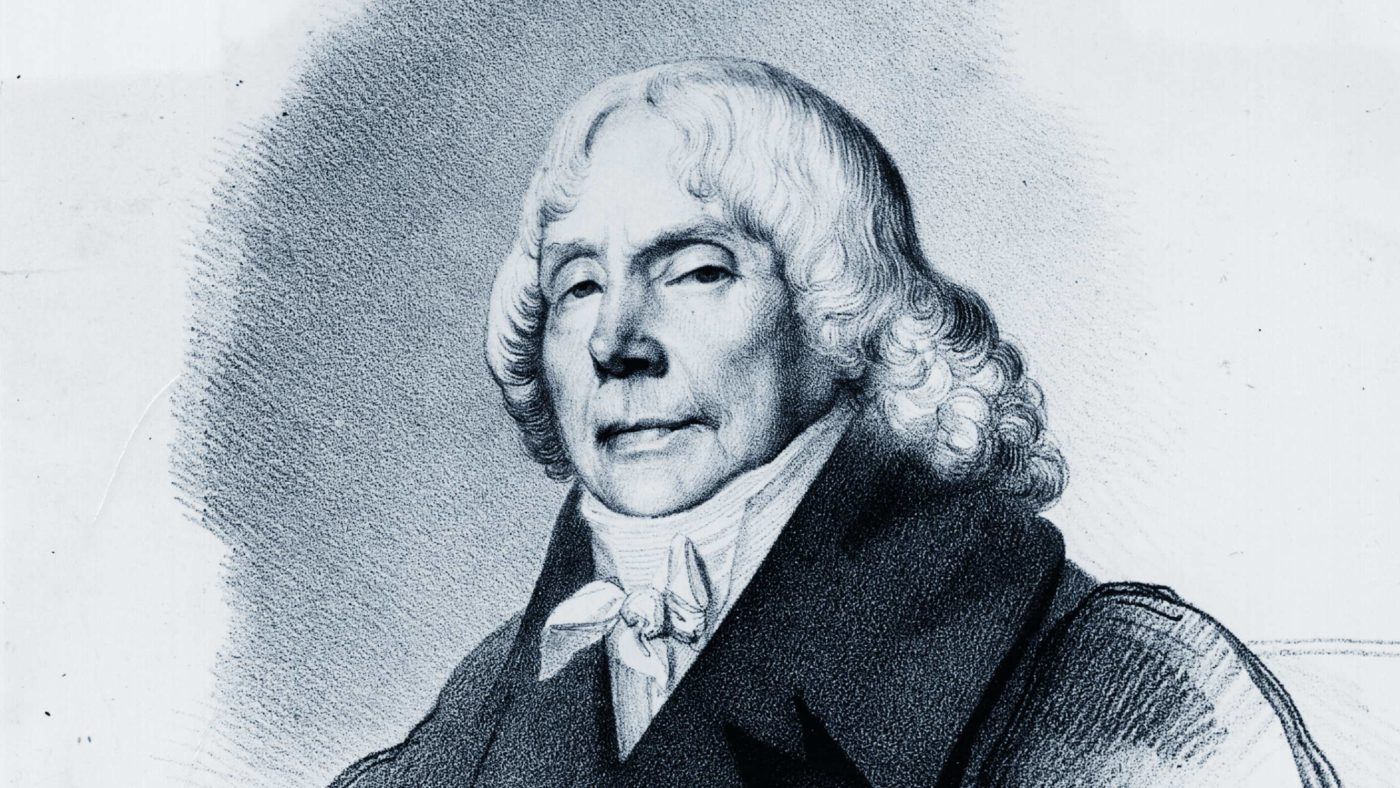

One of the great historical biographies is of the French statesman Talleyrand, by Duff Cooper. It used to be compulsory reading for smart political thinkers, reflecting, from the safety of the sun lounger, on adapting their philosophy to reality.

Charles-Maurice, Prince de Talleyrand was a wily cove, serving five different regimes from the French Revolution onwards. By the end of his life he had developed a political theory based around the ancient, shifting concept of “legitimacy”. Talleyrand reinterpreted it as a modern liberal doctrine, based on the democratic consent of the nation. It is now also the key to stopping Brexit degenerating further into an unseemly mess and potentially taking the Tory party down with it.

Duff Cooper (who, incidentally, is David Cameron’s great-great uncle, but don’t let that put you off) shows us Talleyrand in action. In 1814 Napoleon had surrendered and the only option to stop France descending into chaos was to restore the corpulent Bourbon King Louis XVIII to the throne. Talleyrand knew this wasn’t going to work unless Louis was forced to make compromises.

Tsar Alexander of Russia sought Talleyrand’s counsel. Talleyrand advised that Europe’s new order must be based on the new principle of legitimacy. To those who protested that there was little enthusiasm for restoring the Bourbons, Talleyrand said that the existing Napoleonic Legislative Counsel must itself invite Louis to take the throne. To the consternation of monarchists, he recommended that the tricolour should continue to be the flag of France.

A new constitution was drafted under Talleyrand’s guidance. The second article read: “The French people freely call to the throne of France Louis…”. The restoration of Louis was thus achieved and order restored, but only via the explicit repudiation of an absolute monarchy, instead rooting it in popular consent.

Louis proved politically inept and when Napoleon briefly returned the following year, it was by no means a given that the Bourbon monarchy would survive. Talleyrand advised that Louis should not enter France in the company of foreign troops, lest his legitimacy be questioned again.

In a memorandum to Louis, he wrote: “The spirit of the times in which we live demands that in great civilised states supreme power should only be exercised with the consent of bodies drawn from the heart of the society that it governs.”

What relevance, you might ask, does all of this have to the Brexit debate? The answer is that all sides should, for a moment, put aside their demands and start from the position: “How do we achieve a legitimate outcome, which will be practical and be widely accepted?”

Furthermore, the test for legitimacy is not opinion polls or even a second referendum as Vince Cable and Tony Blair – the absolute monarchists of our age – suggest. It is a deal which will be consented to by “bodies drawn from the heart of the society that it governs”. That essentially means institutions, especially Parliaments across Britain and Europe.

If you start from this proposition several truths leap out:

First, the election has changed everything. Britain now has a Parliament which has voted to implement Brexit, but with varying interpretations and degrees of enthusiasm. Abandoning Brexit – which would require not only repudiating the referendum but reversing the Article 50 legislation passed by both the Commons and the Lords – is impossible. It would not pass. There would be uproar.

Equally, inflicting a swift and radical brand of Brexit, crushing the hopes and feelings of the 48 per cent who voted to Remain, is also now unworkable. Since the election, that too would fail to get through Parliament and also lack legitimacy.

Second, any deal must plainly be legitimate to our European partners. To that end, the rhetoric and positioning of some Brexiteers, including latecomers such as Theresa May, is obviously counter-productive. The EU is indeed a nascent Federal State, built on a set of values, which are “drawn from the heart of the society that it governs”. Only by deferring to those values and celebrating collaboration and mutuality will we ever get an acceptable deal. This requires a change of tone and language as much as substance.

Third, while the Prime Minister possesses one component of legitimacy – legal authority – she now lacks two others: moral and popular authority. Put this deficiency together with the previous two points, and it seems abundantly obvious that, in the first instance, only a transitional Brexit which is soft in tone and limited in scope will ever be agreed to by the EU and also get through our own Parliament.

Brexit is not a single event, but a process. Whether it is a success or not depends on numerous actions we take over many years. The majority of those actions are not going to be taken either by Mrs May and her increasingly shambolic Government or by the gerontocratic revolutionaries who lead the Labour Party. There is consequently simply no point in either side falling out with each other over short-term issues.

The challenge is therefore similar to the one France faced in 1814. How do we get through the next few years without tumbling over a cliff edge when the Article 50 deadline nears, thereby triggering an economic or political crisis? If you start with the assumption that the principle of legitimacy is the key, then the answer has to be cobbling together a transitional deal. Only a transitional deal will be acceptable to all sides and only a transitional deal will stave off a disaster. We can revise it later, in a more radical direction, if necessary.

Some say that such a transition should emulate Norway, inside the single market, but outside the EU. Well, maybe. It has its attractions. But Norway effectively runs something called the European Free Trade Area which governs its members’ relationship with the EU. Has anybody asked them if we can join? Surely, from their point of view, having the flatulent British elephant climbing in their neat Nordic rowing boat is not a terribly attractive prospect.

My guess is that a deal more like the Swiss relationship with the EU, which is outside the EEA but inside EFTA and governed by a series of bespoke bilateral agreements with the EU largely outside the scope of the European Court of Justice (including on free movement), is more preferable. But frankly, it matters less what this temporary transition deal is, merely that there is one. The spectacle of the Cabinet falling out in public over Brexit strategy is too embarrassing and too awful to contemplate.

Once Ministers have decided on the nature of a transitional agreement they should then stop squabbling and get on with executing and communicating the policy, so it is “drawn from the heart of the society that it governs”. I am sure Talleyrand would advise this is the only legitimate course.