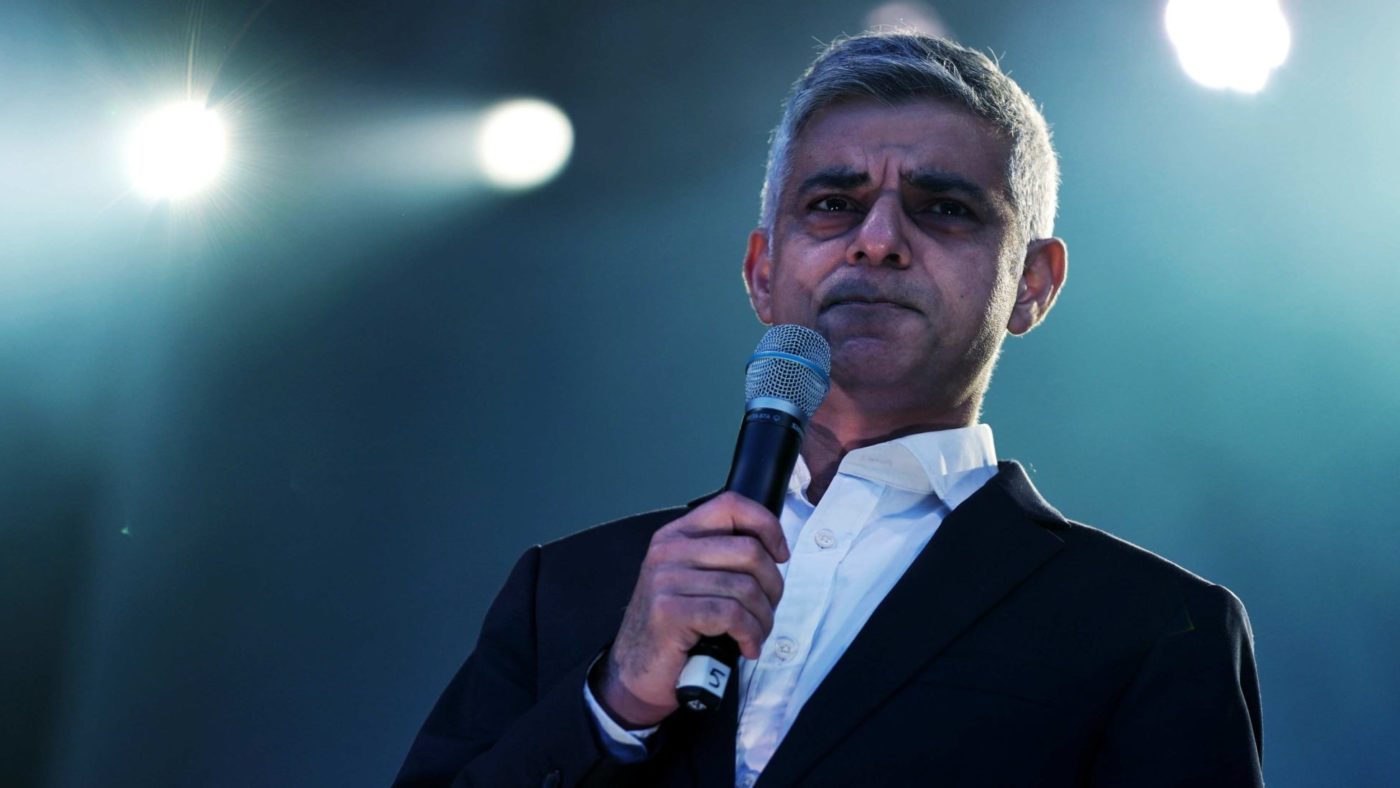

Sadiq Khan has a record that would embarrass even Justin Bieber.

The ‘greatest’ hits London has suffered since his election in 2016 include:

- Robbery up 73%

- Street muggings up 56%

- Homicides up 34%

Not everything is up of course. Transport reliability is down, TFL’s budget has tanked after some very effective self-sabotage, while rates of house building and tree planting are shameful.

But the most damning statistic of all remains the number of murders in the capital: 149 last year, the highest figure since 2008, with knife crime at an historic high. It’s on this miserable record that Khan should be judged in the Mayoral election come May 7th.

Passing the bucks

As Mayor, Sadiq Khan is never more active than when blaming other people for his own failings: he stuffs cotton wool into his ears and points zealously at government cuts to policing in the hope we absolve him of any blame for the bloodshed that has plagued London under his watch.

Of course, the causes of crime are myriad and complex, and not all factors – such as say, family breakdown – are (or even should be) within Khan’s remit. But much as he might wish he weren’t, Khan is not just Mayor of London, he is the Police and Crime Commissioner for the city, the man tasked by law to come up with a plan. And the plan, if we can call it that, has not worked.

For all his complaints about funding, the Mayor controls an £18bn budget. He decides where it goes. And while we’re told there is not enough money for police officers, curiously there does seem to be enough money to increase the number of press officers plastering his name across the city.

Khan has presided over a flabby bureaucracy, bloated on self-satisfaction and more intent on banning Tube ads and pushing for a second Brexit referendum than dealing with the real problems Londoners face. He has not been asleep at the wheel so much as staring at himself in the rear-view mirror. All the while crime ramps up, victims multiply, and the fabric of a city frays.

There was a tacit recognition of this in 2018 when Khan belatedly adopted the public health approach to crime which had proved so successful in Glasgow and New York – and which so many had been calling for. Central to this plan was the establishment of a Violence Reduction Unit (which, for all the moaning about funding, the Government pumped £35m into). But unlike the leaders in Glasgow and New York, who gripped the issue like a vice, Khan has shown all the grip of an amoeba. The Violence Reduction Unit Partnership Reference Group has been going 18 months. It has met 8 times. All the while, the homicide rate has continued to rise.

The experience of other regions in the country that have struggled with cuts to policing underlines how poor Khan’s record is. While London’s homicide rate leapt 10% between 2018-19, the next biggest police force, West Midlands police, reported a near 20% fall in homicides over the same period, while the crime rate has fallen in Greater Manchester by 4.4% under the leadership of Andy Burnham. Other Mayors are getting a grip, but this is Sadiq Khan: the Mayor who can’t.

But it’s not just on public safety that Sadiq has used his Minus touch – on transport, tube reliability has fallen while TFL (which is run by the Mayor) has sunk to record levels of debt, with an operating deficit of almost £1bn a year. When Khan came to power Crossrail was on time and on budget. Under his leadership costs have spiralled and Crossrail been delayed, the Northern Line extension delayed, the Bakerloo line extension delayed, station upgrades from Holborn to Camden delayed, and London’s commuters – you guessed it – delayed, with disruptions due to faulty stock up 30%. That stock could have been invested in, but one of the reasons TFL doesn’t have any money is because the Mayor starved them of it, freezing fares on one-way tickets in a populist move that looks a lot better on a billboard than a balance sheet.

No wonder Khan didn’t so much as mention crime or transport when he launched his re-election campaign this week. It was odd, however, that he wanted us to focus on housing, given that his record on that front – 116,000 homes promised in 2016, less than 20,000 delivered nearly 4 years later – is also embarrassingly bad.

His new answer to the housing crisis though is a remarkably unifying one: Khan’s plan to introduce rent controls achieves the rare feat of uniting both the left and right in condemnation. This policy has failed in virtually every city it’s been tried, and risks freezing rents in a London where, if you’re a nurse or teacher, the average rent is 105% of your salary. As Assar Lindbeck, the economist who chaired the Nobel Prize committee for years reportedly put it, rent controls are ‘the best way to destroy a city, other than bombing’. So, something to look forward to then.

Bubble of Virtue

In short, this is a politician who has shown the kind of rank incompetence that would see him kicked out of a job in any other walk of life. That he has even a chance of running the UK’s largest city for another four years should be galling to Londoners. And yet judging from the early opinion polls, it’s not, with Khan sitting fairly comfortably ahead of his main rivals, Independent Rory Stewart and Conservative Shaun Bailey whose route to victory depends on one of them moving early into a decisive second place and hoovering up a majority of second preference votes. This lead could of course be a reflection of the fairly limp Conservative campaign, or Stewart’s lack of party machine, but there’s something else at play too.

Khan seems to exist in an impregnable bubble of virtue that no number of stabbings can burst. This is partly because he appeals to London’s sense of itself. The fact a diverse, left-leaning city elected a left-wing Muslim mayor, the son of a bus driver, who grandstands against Brexit (despite having no say over the matter) makes London feel superficially good about itself. For Khan, as his manifesto makes clear, it’s not about policy it’s about personality, it’s about leveraging his identity to signify a set of vague, almost unchallengeable values that are meant to be ‘London’s values’. Detail doesn’t matter to his strategy, what matters are things like he is ‘leading the fight against Brexit’. Who cares if that question has in fact been settled? In London it’s a socially virtuous (and ultimately vacuous) thing to say, which shows certain type of voter that he’s in the same bubble as they are – he gets you, and that matters.

And then there’s his trump card. Khan’s well-publicised spats with the US President are an underpriced source of political strength in this race. For many, Trump’s animosity signals Khan’s virtue, and implies a vote for Khan is a vote against Trump and what he represents.

Indeed the best thing that could happen to the Stewart of Bailey campaign would be for the US President to send some flak their way. Such are the times we live in.

Re-making the world

Despite this bubble of virtue, it’s clear what a second term of Sadiq would mean for Londoners: wasted money, wasted hours and wasted lives.

But it also means something less quantifiable and more insidious for London itself – wasted opportunity.

We are living through a period of profound change for global cities in the West, with devolution at home and collaboration abroad on a new metropolitan agenda still taking shape. From Seattle to Gdansk, Madrid to New York, cities are remodelling the relationship between citizen and state, and are strengthening ties between each other in an attempt to mitigate the effects of global withdrawal, driven by more protectionist national governments. The opportunity is there for London not just to shape the agenda but to lead, if only the Mayor could see it.

Sadly, in Sadiq Khan, we have a mayor who can’t.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.