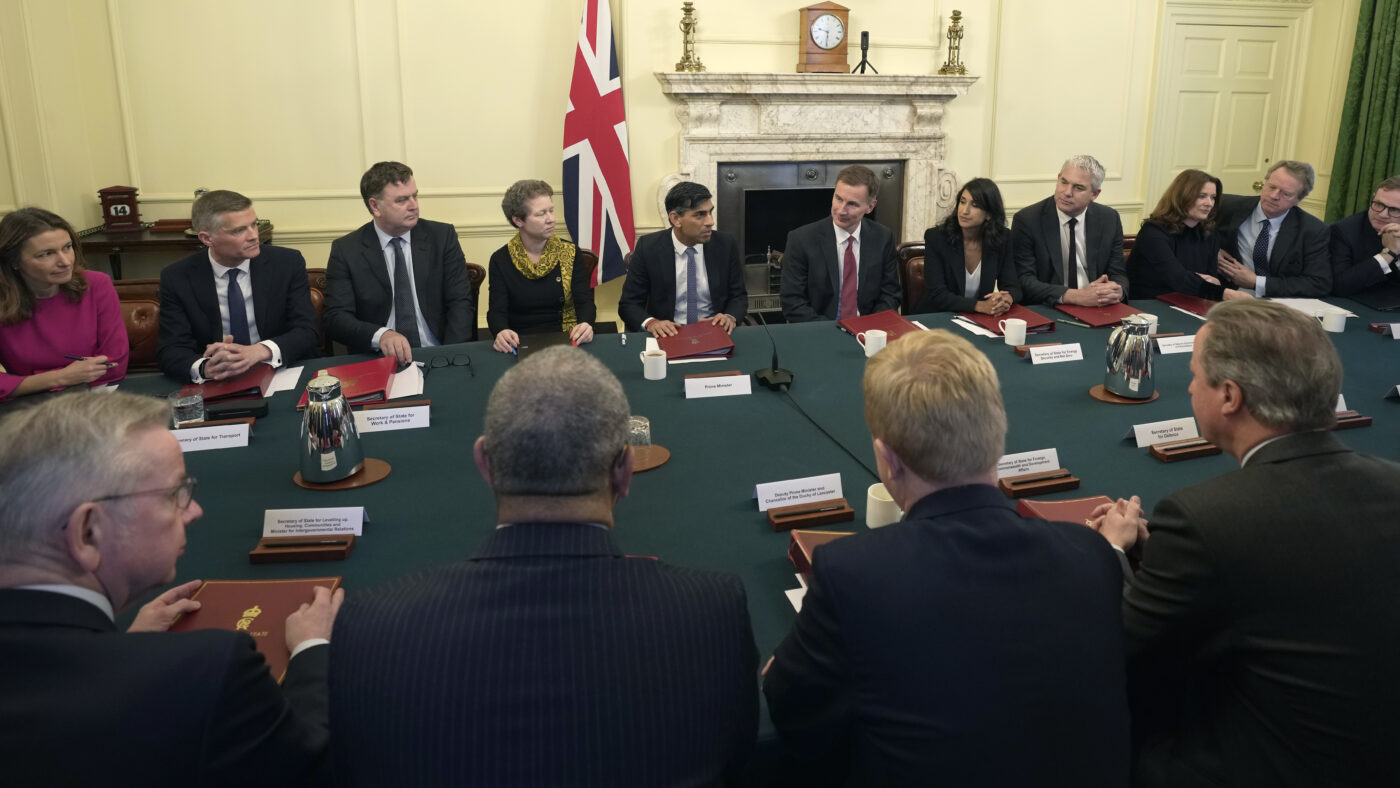

Rishi Sunak finally has a Cabinet cast in his own image. The question is, will it do him any good in the face of a 20-point poll deficit and an in-tray of intractable problems his government shows no sign of solving or even, in some cases, much interest in?

It will obviously help to have dismissed Suella Braverman. Whatever your view of the former Home Secretary and her politics, the principle of collective responsibility is essential to even minimally-effective government.

Yes, the Conservative Party is a broad church, and there is often some utility in having people from different wings of it with some licence to sound off. But that is a difficult balancing act for a loyal minister, not a licence for mutiny.

Thanks to Braverman’s interventions on rough sleeping and ‘hate marches’, the past two weeks – in which the main story could have been Labour’s divisions over Gaza – have instead been dominated by stories about Tory splits as her Cabinet colleagues repeatedly distanced themselves from her comments.

He will be better off without that. Yes, some of her supporters are threatening to ‘raise hell’, according to media reports. But with such a thin King’s Speech, there isn’t an awful lot to threaten in legislative terms.

Meanwhile it’s hard to imagine many MPs following Andrea Jenkyns’ lead and sending in a letter to Sir Graham Brady, for one simple reason: who on earth is the challenger who wants to try and seize the crown now, with the party heading for a crushing defeat in 12 months’ time?

Braverman’s dismissal set the tone for the rest of the reshuffle, which has been broadly taken as a shift back towards the party’s liberal wing (or ‘the centre ground’, as the holders of these sometimes unpopular positions insist on calling it).

The decision to bring back David Cameron – which surely did its job of being the story and stealing the former Home Secretary’s headlines – is a fascinating one for several reasons, not least that this will be the first time a former Prime Minister has served in a subsequent government since the 1970-74 parliament.

But it could also be intended as a big signal to voters in the so-called ‘Blue Wall’ – traditional Conservative seats in the South which are now more vulnerable than they have been in a generation – that the government is on their side.

That’s a gamble. As some have pointed out, there is also a chance that Cameron will alienate many of the voters won over to the party in 2017 and 2019, in the wake of Brexit, and who thought they weren’t voting for the ‘same old Tories’. It also sits very oddly with Sunak’s bold talk in Manchester about rejecting 30 years of a broken consensus.

Yet if CCHQ is planning on fighting a defensive election with limited resources, focusing on middle-class voters who have drifted away from the party since the referendum is probably a sensible decision.

If the realignment is real – and despite the fact it may appear to unwind next year, I think it is – then the Red Wall will be in play for the Tories at future elections, even if they’re routed there now. The factors which have alienated those voters from Labour won’t have gone away, and having broken the habit of lifelong loyalty those constituencies will be receptive to future pitches from a revived Conservative Party.

On the other hand, any seat they lose in the Blue Wall could be lost for a generation. The Liberal Democrats are very good at getting thoroughly entrenched once they capture a constituency; it took them entering government, and finally having to take ownership of unpopular national decisions, for the Conservatives to win back those areas like the South West they lost in the 1990s.

Meanwhile, the worsening housing crisis in London means the capital is continuing to radiate angry voters into the capital’s commuter belt. Over the next ten years we may see many more shire strongholds go the way of Brighton and Canterbury, both now in the Labour column – especially if Sir Keir Starmer makes good on his promise to relax Green Belt restrictions and build thousands of homes in all those marginals.

There’s only one wrinkle in this analysis. If Sunak’s intention with the reshuffle was a pivot towards a Blue Wall-facing strategy, why has he made Richard Holden the new Party Chairman? Holden currently sits for North West Durham (formerly home to Laura Pidcock, the Corbynite), and is part of the 2019 intake.

Even if he ends up safely ensconced somewhere else following the boundary review, he is surely unlikely to sign off on a campaign strategy that writes off so many of his colleagues who were first elected under Johnson. We’ll have to see how those tensions play out.

Ultimately though, the reshuffle in itself is unlikely to make more than a marginal difference to the election – and perhaps, if you’re feeling cynical, to the next year of government. Even the most able minister can only be effective if they have a clear programme, backing from the top, and sufficient time (i.e. years) to get to grips with their brief.

In recent years, the Conservatives, riven by so many changes of leader and direction, have proven totally incapable of creating those conditions for success. Now there is no longer sufficient time for this government to replicate the success that, for example, Michael Gove and Nick Gibb had at the Department for Education, even if the personnel and the plan were there. And there isn’t much evidence of either.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.