Why should we care about freedom of expression? In the real world of distraction and opportunity, the issue can seem abstract, and therefore unimportant. It’s a question to which we might just respond: “I can think what I want, can’t I?”, or, “You’re not seriously suggesting I can’t have my say?” Too often we continue on, oblivious until abstract fears become reality.

In 1917, a boy witnessed a crime: a policeman “being dragged off, pale and struggling, by a mob, obviously to his death”. In the 1990s, the boy — whose name was Isaiah Berlin, and who had become one of the greatest thinkers of the twentieth century — described the event as “a terrible sight that I have never forgotten”. It was clearly a formative experience, not least because he is best known for his defence of freedom and opposition to totalitarianism.

I was reminded of this famous tale from Berlin’s childhood while reading Conservative MP Kemi Badenoch’s new paper for Freer, the political initiative that I direct.

Kemi has written a compelling and thoughtful defence of free expression that — like Berlin’s — is backed-up by personal experience from her childhood in Nigeria. As well as memories of riots taking place following a state-sanctioned unlawful killing, she describes witnessing a lynch mob beating a man to death on the street.

Not everyone has had such experiences. And not everyone who has had them has gone on to stand up publicly against the suppressive political systems under which these things most easily take place. Not everyone who has seen suppression — whether by the state or the mob — goes on to fight for freedom. Or even to believe in its importance. Barbarous experiences remind us of our obligations to respect one another, but depending on those experiences, alone, for moral backup, is a risky approach.

Being free to express ourselves — to speak freely, to think freely, to act freely — is a fundamental right, conferred upon us by dint of our shared humanity. Recognition of this is a crucial ingredient of a good society. And awareness of these things should be some of the most natural thoughts we possess.

In any society, however, the right to freedom comes with qualifications. With rights come obligations, and, to live together peacefully, we must accept some rules and limits.

When thinking about this, John Stuart Mill’s “harm principle” — that “the only purpose for which power can be rightfully exercised over any member of a civilised community, against his will, is to prevent harm to others” — always seems like a good place to start. Yet, many questions still arise, not least, what might constitute “harm”.

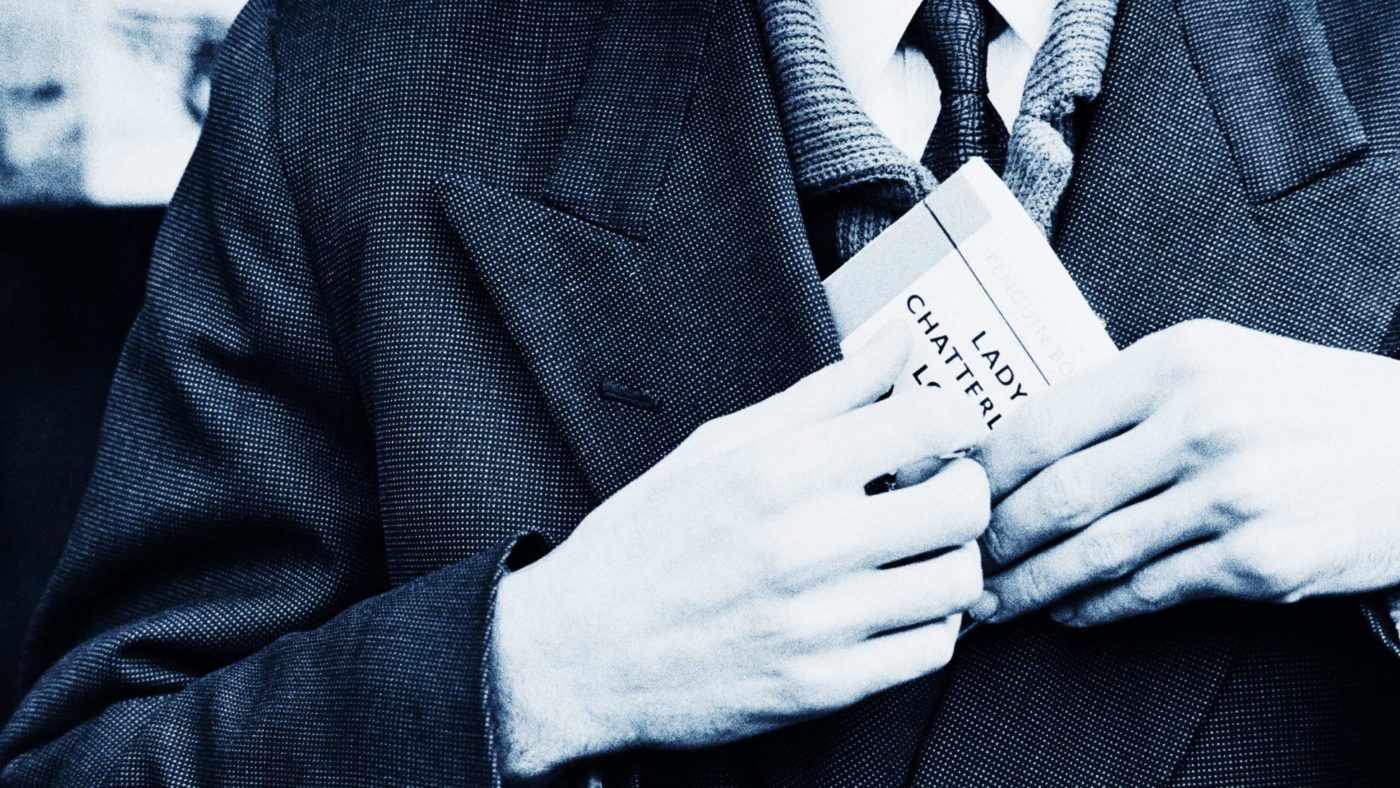

As Kemi points out in her Freer paper, necessary qualifications to free speech are in need of reassessment “throughout the ages”. After all, it’s been a long time since Mill deliberated where to strike a justified societal balance between freedom and security. There was no internet back then, and there was no Twitter. And it’s taken centuries to get where we are in terms of access to news and comment: the Daily Telegraph, for instance, was founded only four years before Mill wrote On Liberty. Kemi’s paper addresses how we might begin to think about this topic in an age in which “virtual lynch mobs […] are congregating to intimidate people of all walks of life”.

Half the battle is working out where we need to focus our attention. Choosing not to invite a particular speaker to an event is not usually a suppression of free speech. Whereas banning someone, or preventing them from speaking at an event at which they’ve been invited to do so, often is.

Similarly, there are differences between private events and public events, between private spaces and public spaces, and between those things that are a matter for law and those that aren’t. Free speech is not an issue just for the state or for lawyers. Supporting such freedoms is a public good, and it’s an issue for us all.

It’s too often forgotten that thinking something is wrong is not the same as thinking it should be against the law. And it should not be the case that we choose to behave well just because the law instructs us to. I don’t refrain from bearbaiting just because it’s illegal. And I can choose not to call you offensive names without there being a law against it.

Taking away our choice not to be offensive, however, not only reduces our need for personal responsibility, it also brings subjectivity into law making and enforcement — something which is already a problem regarding the determination of hate crimes.

It can sound hyperbolic to talk of fundamental ideals on which our liberal country is based. It can seem over the top to suggest that such ideals are at risk. After all, people aren’t being killed on our streets by lynch mobs, are they? But that is exactly why we need to learn from people who, like Berlin and Badenoch, know what suppression of free expression looks like. They have used the experiences they have suffered to strengthen their arguments, and recognise the need to ask some hard questions about our society and how free we truly are.