I never put too much faith in surveys, but I was heartened to see one published today suggesting that Britons are more favourably disposed to the rich than people in France, Germany and even the United States. Moreover the survey suggests that millennials, for all their flirtation with Corbynmania, are more supportive than any other age group.

These findings go against the belief that the rich are widely resented. I have been struck, in researching for a forthcoming book, just how academics and politicians have swallowed this line. Not just those on the left, either: we recently had the weird spectacle of a Conservative minister. Caroline Nokes, asserting that no one should get a salary of more than £1 million a year.

Perhaps this is a rogue survey. But there are certainly grounds for scepticism about many of the charges against the rich. The vast majority of those on the Sunday Times Rich List last year are self-made entrepreneurs rather than scions of old money. And whatever shenanigans some of them may get up to in order to minimise tax liability, collectively they pay a heck of a lot towards our never-ending government spending spree. Individuals such as Sir James Dyson (£128m) and families such as Bet365 owners Denise, John and Peter Coates (£156m) are amongst the highest taxpayers, while the top 1 per cent collectively pay 28 per cent of all income tax and substantial proportions of other taxes. In the absence of the super-rich the rest of us would have to pay substantially more in tax to sustain the levels of government spending we’ve become used to.

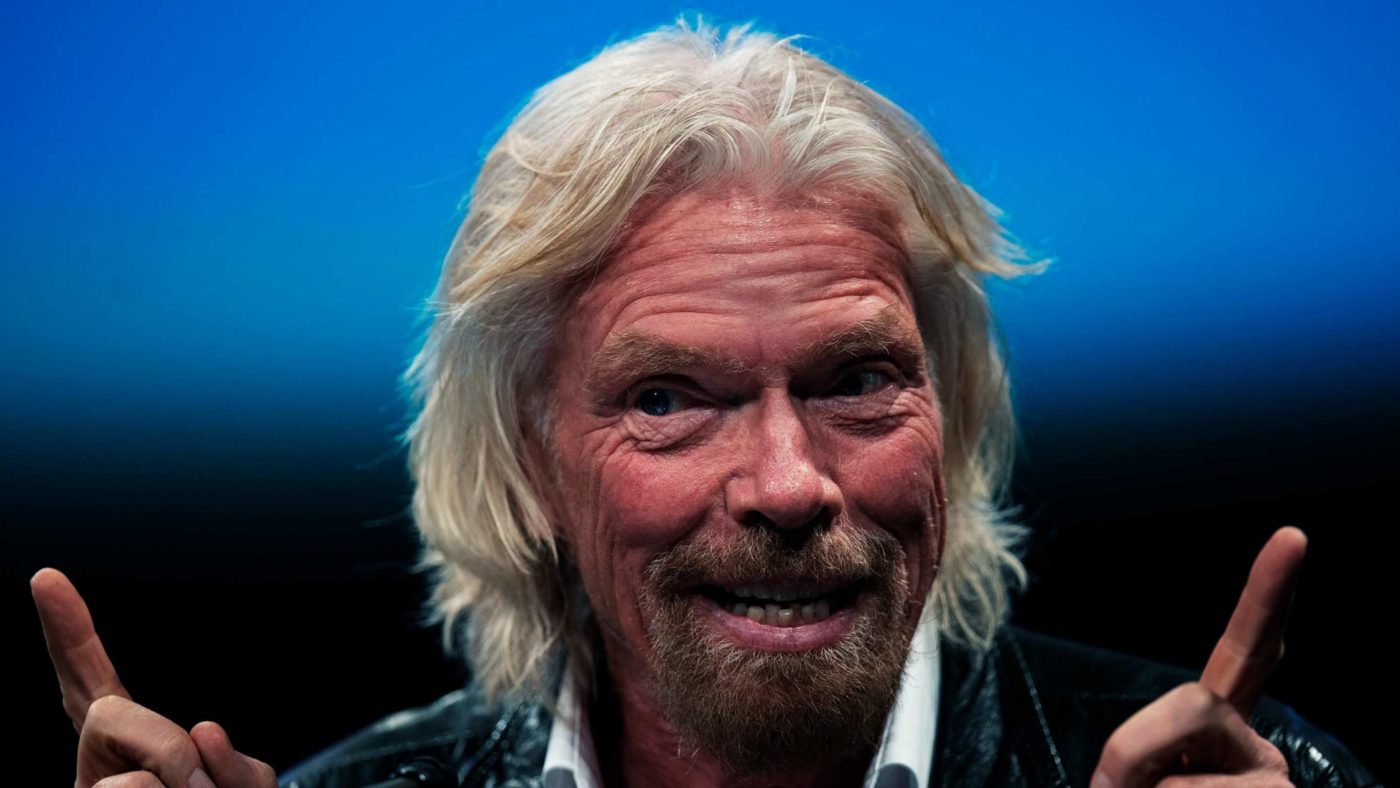

Tax is not the only contribution made by the rich to wider society. Independent sources of wealth enable investment in fanciful new technologies (think Richard Branson and Elon Musk) to which no government funding – and precious little outside investment – would ever be given. Charities and educational institutions (think David and Claudia Harding’s £100 million to Cambridge a couple of weeks ago) are obvious beneficiaries, as is research. The Wellcome Trust (set up by Sir Henry Wellcome from the spoils of what we would now call Big Pharma) is our biggest private funder of medical research.

In order to get rich, most people will need to accumulate wealth from high incomes, so Nokes-style restrictions would limit the chances of future generations doing so and ensure an ever-greater concentration of power in state hands. Current high earners include footballers and actors and YouTubers (Dan TDM made £14m last year). But politicians’ hostility is mainly directed against high earners in positions of responsibility. There are now effective upper limits on what can be paid to people in public sector jobs or in universities (where any salaries over £150,000 have to be approved by the Office for Students). And of course there are company CEOs.

So far the current government has confined itself mainly to placing requirements on large listed companies to publish pay ratios, and for remuneration schemes to be voted on by shareholders. But there are signs that it may take matters further (for instance by ‘encouraging’ unlisted companies to accept the Wates report proposal that they copy the listed sector). And the Opposition is suggesting a far tougher regime, with maximum 20-1 ratios between the highest and lowest paid in renationalised utilities and major outsourcing firms, plus worker representation on company boards across the economy.

Much of this enthusiasm for private sector intervention is based on the belief that CEO pay bears no relation to company performance, that there are excessive ‘rewards for failure’, and that pay-setting is rigged by unrepresentative remuneration committees. Careful research indicates that these claims are greatly exaggerated.

Another argument often adduced is that CEOs of large complex firms have little influence over the workings of their organisations, and largely play a figurehead role for which they do not deserve high pay. This is, however, not what investors seem to believe. Tidjane Thiam was in the news again last week, as he is being touted as a replacement for Christine Lagarde at the IMF. When he moved from Prudential to Credit Suisse in 2015, Prudential’s share price fell by 3.1 per cent, knocking £1.3 billion off the firm’s value. Credit Suisse’s shares rose by 7.8 per cent, adding £2 billion to the company’s value.

Whatever the strengths and weaknesses of some CEOs, a rigid application of pay ratios or pay caps would have undesirable side-effects. Currently 40 per cent of FTSE-100 CEOs are non-UK nationals: we have one of the most open systems of recruitment in the world. Restrictions on pay would remove this source of competitive advantage. It would squeeze the pay of middle-managers and technical experts within companies, not just top management. And in an environment where companies with high pay ratios are named and shamed, some businesses might increase their flexibility on top pay by reducing recruitment at the bottom, or outsourcing low-paid work. This would not benefit those at the bottom of the ladder.

In the long run, too, it seems likely that restrictions on pay of CEOs would lead to wider restrictions on pay and on wealth, as “whataboutery” would become a blood sport amongst the political classes. Why should a busy CEO responsible for billions of pounds of investment and hundreds of thousands of jobs, be paid a fraction of the earnings of, say, Simon Cowell (£35m last year)?

Most policy interventions, however misguided, usually have the intention of benefiting some group or other. Restrictions on pay and wealth have no direct benefit to anyone. If our millennials are indeed sensible enough to see this, and prefer channelling Peter Mandelson (famously ‘intensely relaxed about people getting filthy rich’) rather than Caroline Nokes, it’s great news. But given our current crop of virtue-signalling politicians I’m not that hopeful.