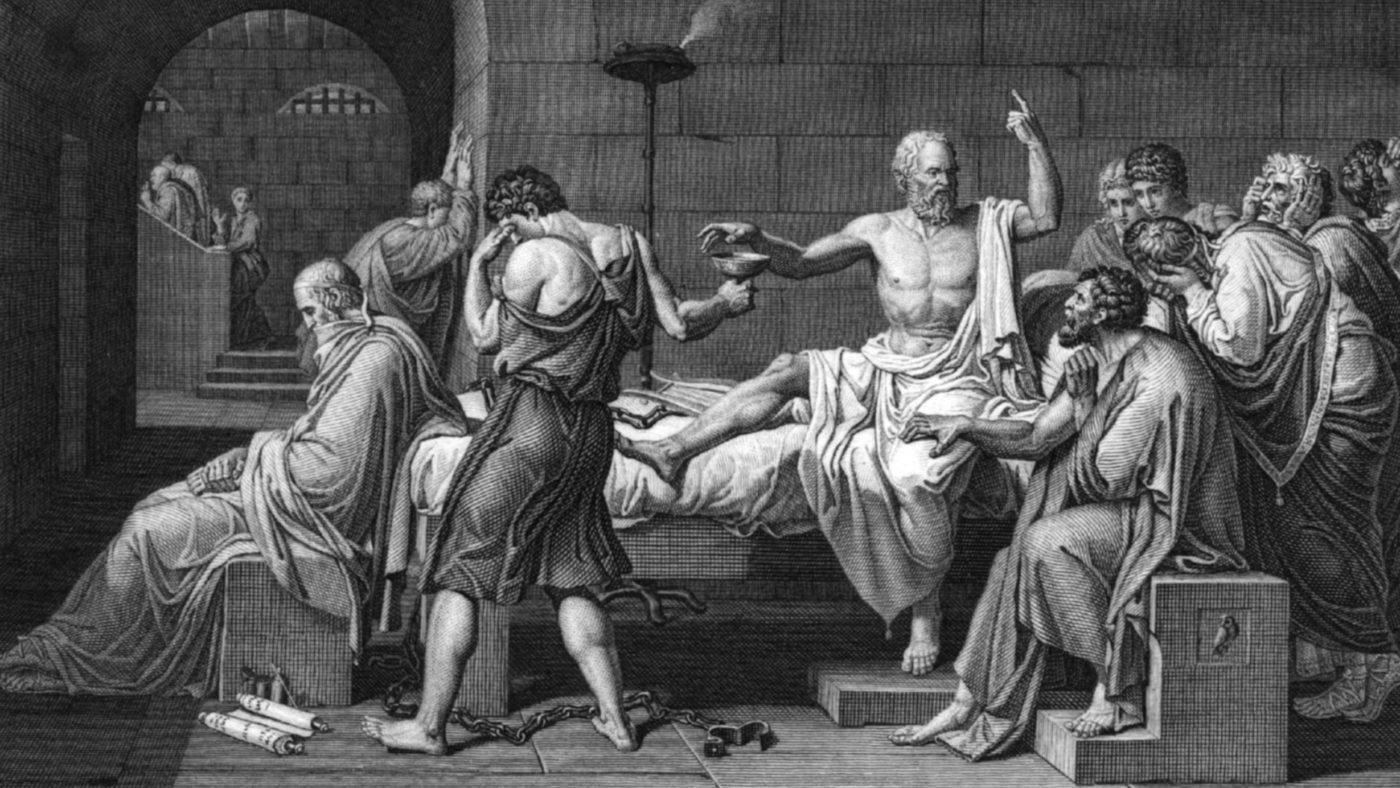

For over two thousand years political philosophers have grappled with the concept and nature of ‘political responsibility’. In Plato’s Crito, in which he narrates one of Socrates’ final conversations before his execution, he describes how Socrates declares that he cannot go along with the escape plan that Crito and other of his friends have arranged. Crito is amazed and asks why not. Socrates tells him that as an Athenian citizen he has “agreements and commitments” to Athens, and he cannot escape them. Fleeing would be to “mistreat” his friends, his country, and the laws of Athens. And rather than ignore his moral duty he stays and drinks the hemlock.

That’s certainly an extreme example of political responsibility, but like much that Plato wrote, the heightened nature of the example he gives us presents all the more clearly the issue that he wants us to contemplate. What Plato’s Socrates outlines is basically an Ancient version of the Social Contract – by which citizens ought to demonstrate moral courage in pursuit of political responsibility.

It’s a great idea, and Socrates’ extreme stance is admirable. For if moral courage is defined as doing the right thing even at the risk of inconvenience, ridicule, punishment, loss of security or social status, then Socrates had it in spades.

But if citizens are required to show moral courage and political responsibility, what about politicians themselves? How does political responsibility govern their choices? And what does moral courage look like for them?

In answering that question it’s easier to describe what moral cowardice looks like. I have just seen the cover of a Danish newspaper which features photographs of David Cameron, Boris Johnson and Nigel Farage, each sipping from a mug or a pint glass, with the caption “BREXIT? NOT OUR PROBLEM!” That says it all. The unpleasant fact is that our politicians seem more estranged than ever from the concepts of moral courage and political responsibility. Those principles have been replaced by self-interest and power games, and never has the description of politicians as “unaccountable elites” seemed more accurate.

Of course, the image of politicians as a bunch of self-serving egomaniacs is not new. The opening scene of Shakespeare’s Coriolanus has the irate “First Citizen” responding to the assertion that politicians “care for” the people with the following tirade: “Care for us! True, indeed! They ne’er cared for us yet: suffer us to famish, and their storehouses crammed with grain; make edicts for usury, to support usurers; repeal daily any wholesome act established against the rich, and provide more piercing statutes daily to chain up and restrain the poor. If the wars eat us not up, they will; and there’s all the love they bear us.”

Three centuries later it seems that a significant number of the British population feel exactly the same.

The referendum result was a furious demand to be listened to. For millions of voters at both ends of the political spectrum, whose votes in the last General Election didn’t seem to count, and who feel willfully ignored by their so-called representatives in Parliament, it was pretty much the British version of the storming of the Bastille. We’ve all heard the post-referendum interviews with people saying they weren’t really voting to leave the EU, but that they ticked the “Leave the European Union” box in order to send a message to politicians. They were given this one opportunity to have a voice and they seized it. They roared, and Brexit is the result.

In the military, “desertion” is a serious offence and carries a custodial sentence. Now, I’m not saying that we should lock politicians up who don’t stick around when they going gets tough, but the fact that the British military – who take the concepts of courage, integrity and loyalty more seriously than most – take such a strong line on responsibility and duty should tell us something.

Should politicians be allowed to throw the towel in as soon as things start to go against them? Do the people who create a “mess” have a moral duty to stick around and clear that mess up? I think they do.

David Cameron would probably claim that he had a duty to resign following the referendum result, but I would like to question the reliability of the moral compass he’s using. I’d go further and say there’s a good case for saying he ought to have remained in post until the people who elected him had given their permission for him to resign. What would have happened if he’d gone back to the Conservative Party and asked for permission to resign? Would they have felt that he had a duty to see Brexit through?

And Boris Johnson and Michael Gove: I am sure I’m not alone in feeling that having careered around the country trumpeting the case for leaving the EU so loudly from that bus, they have a duty to behave soberly and responsibly in the aftermath of the result, rather than indulge in personal power politics and party squabbles. As for Nigel Farage, well, in response to his resigning as Leader of UKIP while continuing to take his salary and claim expenses as an MEP, I can only quote A.D.M. Walker who, in his 1998 paper about political obligation offered the maxim that “The person who benefits from X has an obligation of gratitude not to act contrary to X‘s interests.” Well, quite.

Of course there are plenty of decent, loyal, and courageous politicians left who have a strong sense of duty to the people they represent. And it’s to them that we’ll be turning when the deserters have all finished deserting and the dust has settled on our post-Brexit reality. We need these politicians to show moral courage and determination. We need them to stick it out and serve our best interests in the process. The events of the past two weeks have thrown some extraordinary challenges before them and now more than ever we need our leaders to stand firm and see us through. It’s not as if we’re asking them to drink hemlock after all.