The first instalment in CapX’s series on the battle of economic ideas and public opinion looked at attitudes towards abstract ideas like capitalism and socialism. This week we focus on a more specific battleground: attitudes to business.

Rightly or wrongly, people associate business with capitalism. In many cases they may even treat the two as synonymous. And so attitudes to business are, to an extent, a reflection of attitudes to the economy more generally. But, as our polling reveals, peoples views are more nuanced than they are generally given credit for.

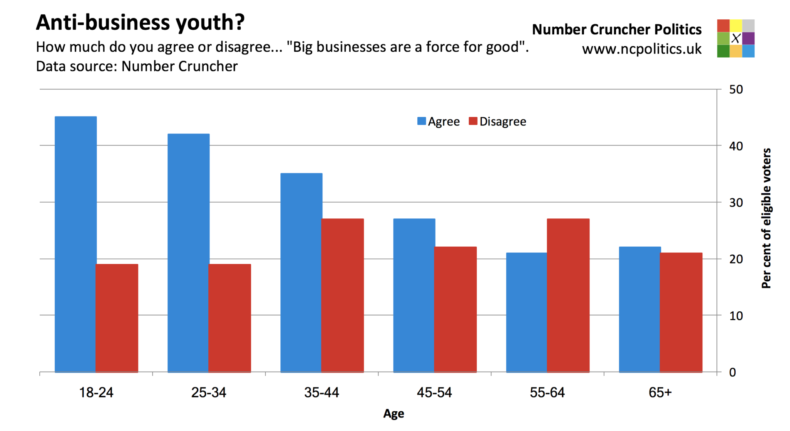

The Number Cruncher poll tested three statements relating to business. Respondents were likelier to agree (30 per cent) than disagree (23 per cent) that “Big businesses are a force for good”. But almost half were on the fence, with 41 per cent saying they neither agree nor disagree, and six per cent unsure.

As was the case with our questions on capitalism and socialism, the party effect is clear and significant, but Conservative voters were less likely to agree, and Labour voters less likely to disagree, than might be expected.

What was not expected is the difference by age. The proportion disagreeing that big business is a force for good varied little across age groups, considering the margin of error that would be expected from subsamples of between 100 and 200 respondents each.

But millennials were significantly likelier than pensioners to agree (and less likely to be neutral). Fully 44 per cent of under-35s see big business as a force for good, as compared with precisely half that proportion (22 per cent) of over-65s.

As is well known, Tories tend to be older than Labour supporters, meaning that if we control for the party effect, by looking at the age effect within each party’s support, the pattern becomes stronger still.

It is interesting to consider the possible explanations for this age pattern, which runs counter to prevailing political stereotype of left-wing younger generations. There are no obvious clues in the data.

It’s conceivable that, for example, younger adults associate big business, either in name or in concept, with technology and things they like, while their elders associate them with things they don’t like, such as the closure of traditional high street shops and post offices, but that is no more than a theory.

It is also that people who came of age in the era of globalisation have known nothing else. That, though, doesn’t fit well with the higher proportions who neither agree nor disagree within the older age groups.

Might people look at big business through the prism of Brexit, resulting in supposedly left-leaning but solidly pro-EU youngers counterintuitively siding with pro-EU big business? It would appear not, because if that were the case, we would expect there also to be a big difference between Remainers and Leavers, whereas in the event there was almost none. This, then, is something of a puzzle.

We then probed agreement or disagreement with the comparative statement “we should worry more about big business than big government”. Thirty-four per cent agreed, 18 per cent disagreed. Again, almost half (49 per cent) didn’t indicate a leaning either way. And unlike the first question, there were no clear patterns in terms of demographics or politics.

So the British public is neither uniformly friendly nor uniformly hostile to big business. But with relatively few don’t knows – far fewer than on party voting intention for example – the balance of public opinion doesn’t seem to be indifference either.

Instead it seems that a plurality of the electorate sees some ways in which big business is a force for good and other ways in which it is not.

That isn’t entirely surprising; few would sincerely claim that there is either nothing bad or nothing good about big business (or for that matter, anything). But it is nevertheless an important reminder that not everything is irredeemably polarised.

What about one of the central tenets of free-market economics, that of competition between businesses? On this, there was no competition.

Two-thirds (67 per cent) agreed that “all businesses should be exposed to competition”. Five per cent disagreed, with far fewer (22 per cent) neither agreeing nor disagreeing than on the first two questions.

As with the second question, there was relatively little variation between the answers from different groups. Younger respondents weren’t as likely as older respondents to back competition (54 per cent of under-25s, compared with over 70 per cent in each of the four over-45 age groups) but a majority in every age group did.

Big business often gets a bad press, which may well contribute to the perception that it’s widely seen as a force for ill. But as is the case on so many topics, public opinion is nuanced, and when you ask a representative sample of the public, including the millions who aren’t strongly political, many are genuinely on the fence.

And the assumption that millennials are particularly unimpressed simply isn’t backed up by the data.