Ukraine is back in the news. The country’s conflict with Russia, which has been ongoing since 2014, is heating up again. There is a real possibility that Russian dictator Vladimir Putin will try to grab even more Ukrainian territory in the months to come. The Russians are suffering from an economic downturn caused by Western sanctions and a fall in the price of commodities, and Putin might try to shore up electoral enthusiasm for his party by appeals to nationalism. To make matters even more interesting, the dictator appears to have unleashed an army of hackers to wreak havoc on the U.S. presidential election and The New York Times reports that Donald Trump’s campaign chief, Paul Manafort, may have pocketed up to $12 million from the pro-Russian party of the exiled Ukrainian president Viktor Yanukovych. So, what are Americans to make of Ukraine’s predicament?

Ukraine is vulnerable to Russia’s territorial expansionism – the former has already lost Crimea to the latter – because it is poor and cannot adequately defend itself from its much better-armed eastern neighbor. There are two possible ways in which Ukraine could improve its fortunes. First, it could find a foreign sponsor willing to supply Ukraine with intelligence, sophisticated weaponry and even military advisors. Normally, the United States would fit the bill. After fifteen years of uninterrupted conflict that has cost thousands of American lives and near-bankrupted the U.S. treasury, however, Americans are increasingly weary of lengthy and costly foreign commitments. To make matters more complicated, Americans need Russian cooperation in dealing with the civil war in Syria, the nuclear deal with Iran, as well as a slew of global issues from counter-terrorism to non-proliferation of weapons of mass destruction.

No doubt, Ukrainians will be hoping that the upcoming presidential contest is won by the neo-conservative stalwart Hillary Clinton rather than Manafort’s mercurial ward, Donald Trump. Clinton, who was humiliated by the failure of her Russia “reset,” might salivate at the prospect of giving Putin a black eye, but that is only of limited help to Ukraine. The United States needs Russian cooperation, such as it is, more than it needs to secure Ukraine’s territorial integrity. Sooner or later, Clinton will be forced to negotiate with the Russians in the same way that George W Bush and Barrack Obama did. From the Ukrainian perspective, a Trump presidency would be even worse. Trump’s pro-Russian statements and nonchalant approach toward serious policy deliberations, both foreign and domestic, makes him unpredictable and, therefore, unreliable to America’s foreign dependents.

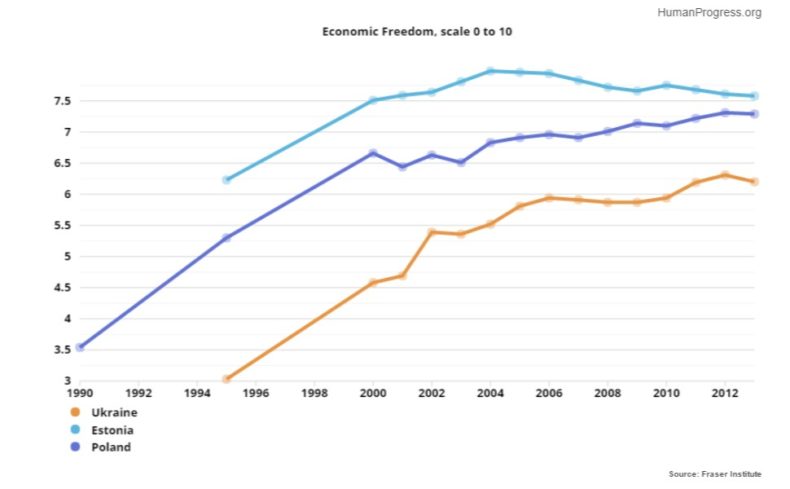

Either way, Ukrainians would be well advised not to put too much stock in American help to keep Russia at bay. Instead, they should look to their own resources. And here Ukraine has a lot of work to do. Ukraine has failed to comprehensively reform its communist-era economy after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991. Unlike Poland, a similarly poor and highly regulated economy in the late 1980s, and Estonia, a fellow ex-Soviet nation, Ukraine’s economic reforms started quite late and were, at best, half-hearted. Today, Ukraine’s economic freedom is similar to that of Ghana and Burkina Faso.

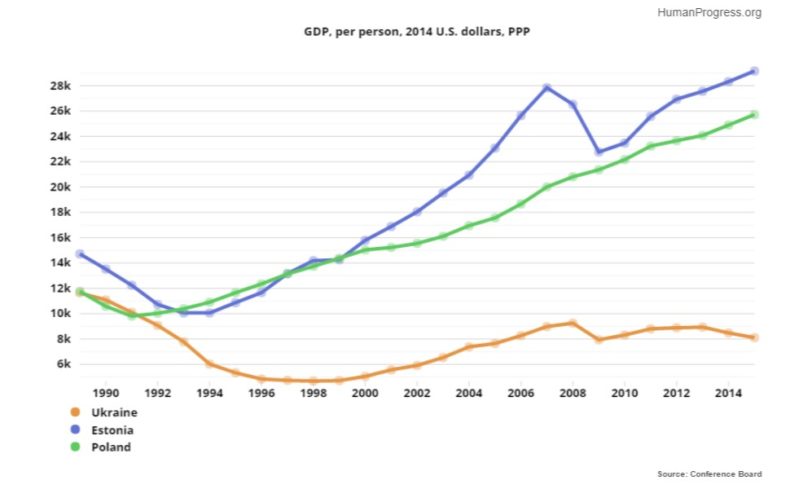

That Ukraine is an economic basket case may be attested to by its per capita income adjusted for inflation and purchasing power parity, which has declined by 30 percent since 1989. Contrast that with Poland, which was as poor as Ukraine in 1989, but which has clocked in a respectable 119 percent increase. Estonia saw its average income rise by 98 percent between 1989 and 2015.

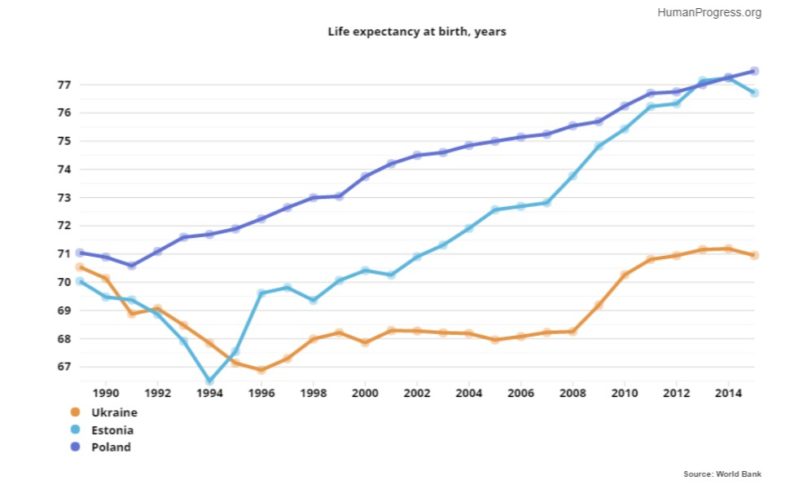

Life expectancy, which is the best indicator of human wellbeing in any given country, tells a similar story. With growing incomes, Estonia and Poland saw their life expectancy increase by 13 percent and 15 percent respectively. Ukrainian life expectancy rose by paltry 4 percent between 1989 and 2015.

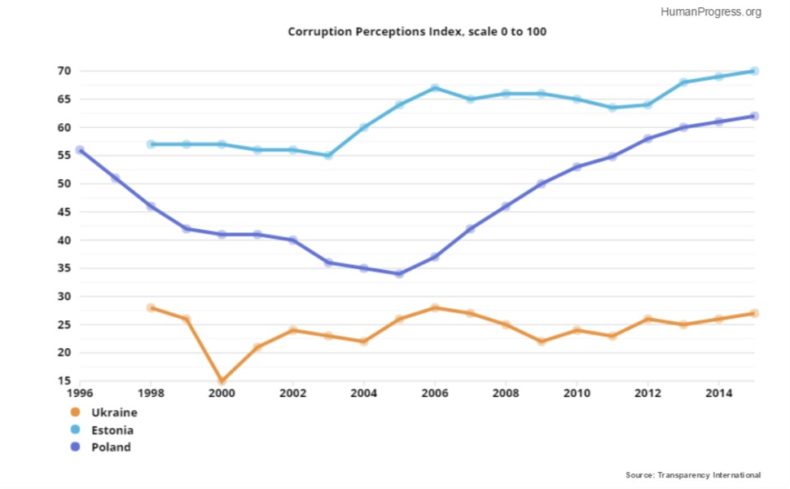

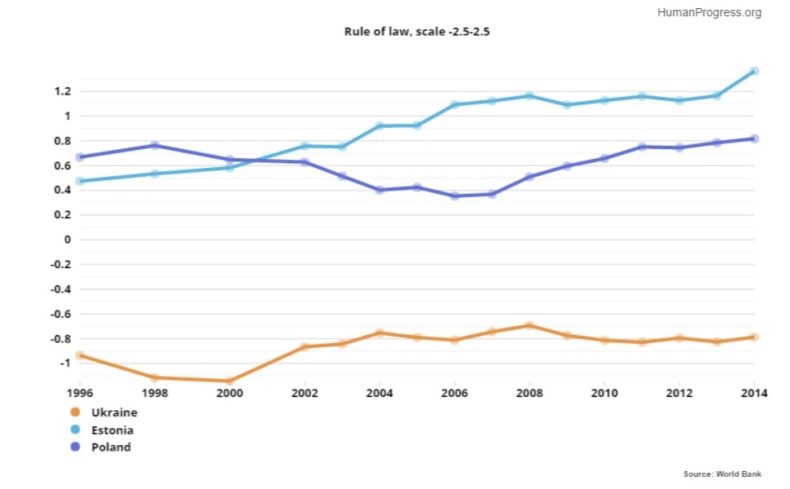

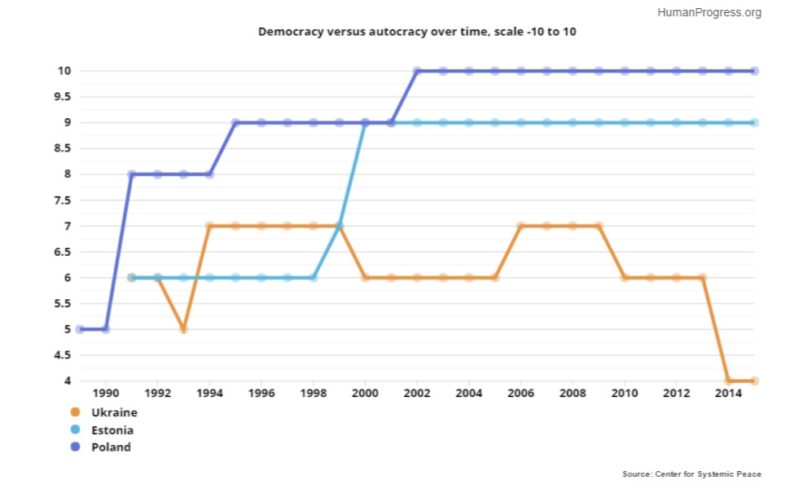

State control of the economy proved to be a breeding ground for corruption – with politically connected “industrialists” snatching the most profitable companies in return for financial donations to their political masters. (Note that the Corruption Perception Index and World Bank’s rule of law indicator start only in the mid-1990s, by which time Poland and Estonia already undertook many economic and political reforms.)

The incestuous relationship between Ukraine’s businessmen and politicians has retarded institutional development in the country. Today, the rule of law and democracy lag behind most other ex-communist nations, including Poland and Estonia.

Ukraine needs to disentangle its political system from its economy. The only way to achieve that is an extensive process of privatization of Ukraine’s enterprises, which should be sold off to the highest – and preferably Western – bidders. Proceeds from privatization could be used to revamp Ukraine’s ailing military and make Russian imperialism more costly. Western countries will be compelled to protect their firms’ investments in Ukraine through diplomatic pressure on Russia. Moreover, Western managers will bring much higher standards of transparency and accountability to Ukraine thus improving that country’s overall business environment. Finally, Western managers will be much less likely to offer bribes to Ukrainian politicians and that, in turn, will have a positive effect on the development of Ukraine’s institutions. Economic freedom, in short, is the only way in which Ukraine’s economy can be reinvigorated, its politics cleansed, its military rearmed and its territorial integrity preserved.