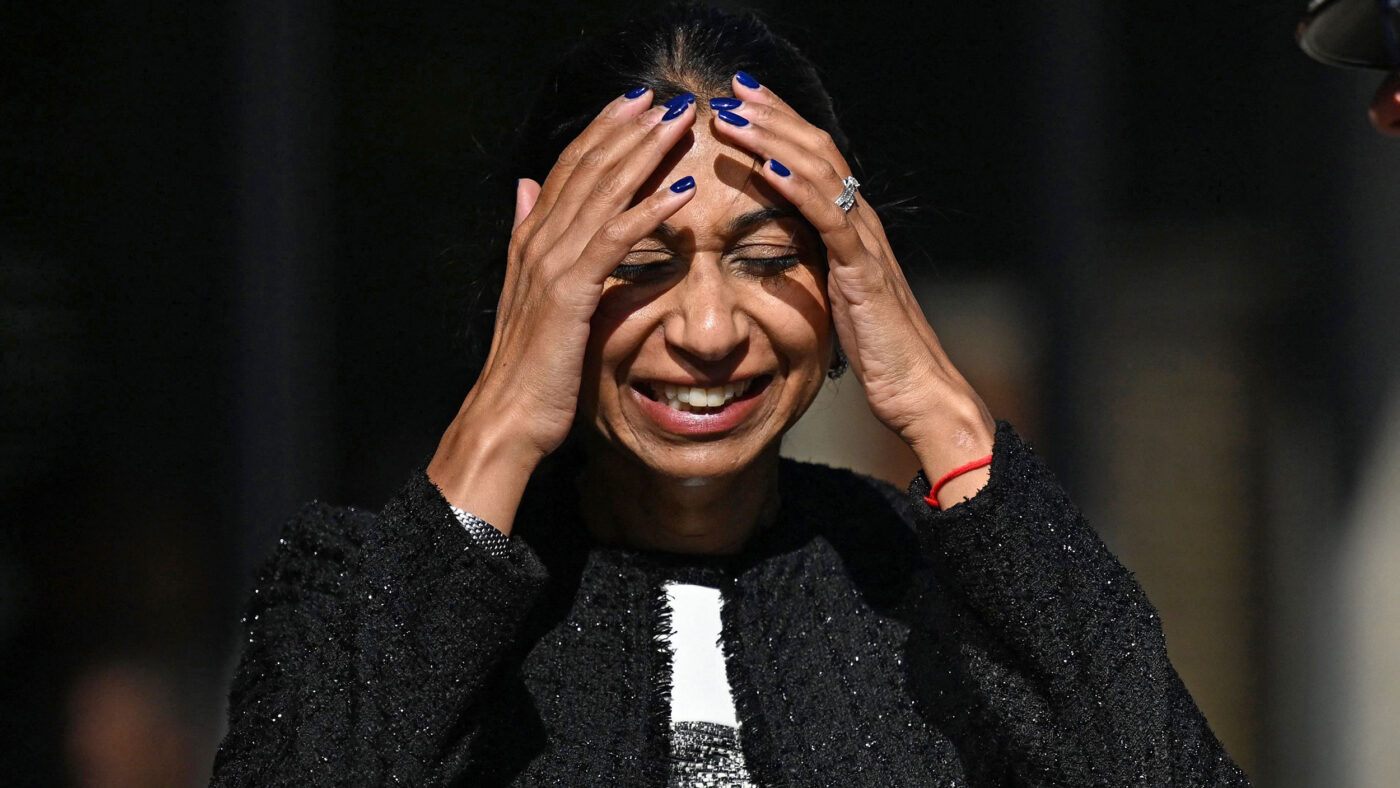

When it comes to commentary on Suella Braverman’s pledge that the police shall henceforth investigate every crime, there is probably no surpassing Duncan Robinson’s ‘Borat Britain‘. For a first-world nation that still at least imagines itself wealthy, how else to respond but ‘Wow! Every crime???’

Yet with crushing predictability, that has not been officialdom’s response. Instead, the Home Secretary this morning stands accused by the National Police Chiefs’ Council (NPCC) of interfering with the operational independence of the police, and of making unrealistic demands of forces already overstretched by what The Guardian calls ‘the squeeze on police funding at a time of rising crime’.

For her part, Braverman insists that the police do have the manpower and resources needed, and that the Government is reducing the burden of ‘needless bureaucracy’ and thus freeing up officers for frontline duties.

However, it is very hard to believe that this new initiative – ‘an extraordinary agreement from all forces in England and Wales’ – is actually going to have the desired effect. It looks a bit like a right-wing analogue of the old New Labour habit of simply setting targets from on high, or the modern progressive tendency to breezily declare something an entitlement or right.

The most obvious mode of failure is that the measure becomes the target, and the whole thing just devolves into a box-ticking exercise. There will presumably be a minimum standard for what qualifies as the police having ‘investigated’ a given crime, and thus a strong temptation to simply ensure that standard is hit, on paper, in every instance – at the expense of more proactive and rigorous investigation.

Resource pressures on the police are very real. Whilst the Government has gone some way to reversing Coalition-era cuts in officer numbers, today’s forces still have to make difficult decisions about how to prioritise resources.

By no means do they always get such calls right; one thinks of the no fewer than six bodies sent to remove some offensive dolls from a pub in Essex (surely a wild over-commitment to deal with a couple of truculent landlords), or the heavy squad sent to drag an autistic girl from her home in Leeds.

Stories like this are why ministers would be well within their rights to push back on the charge of interference in the police’s operational independence.

Yes, it is important that the Home Secretary doesn’t take personal command of officers on the ground, and that people aren’t snatched off the streets at the flourish of a ministerial pen. But the police are accountable to the public through the Government, and general policing priorities are a matter of legitimate public concern.

The apparent retreat from policing so-called low-level crime is also corrosive of public faith in the forces of law. When half of all forces in England and Wales do not solve a single burglary, or when the owners of stolen laptops, phones, and bikes trace them and still the police refuse to take action, it paints a vivid picture of a society in which the rule of law seems to be fraying, and the best many ordinary citizens can expect from their uniformed protectors is a crime number for the insurance company.

But orders from on high will not be sufficient to fix this. Just look at the Government’s plans for sentencing.

Ministers can, and have, amended the rules so that early release will take place after someone has served two-thirds of their sentence, rather than half. But in isolation, all this is likely to do is make the chronic shortage of prison places worse – and that in turn will see judges hand out more lenient sentences than they otherwise might. The Government could, like the old lady who swallowed a fly, counteract that by mandating stricter minimum sentencing. But that would again just exacerbate the cell shortage even further.

(This sentencing crisis directly impacts low-level crime, by the way. Contra judicial reform advocates who focus only on what happens to a prisoner after release, one way prison can keep crime down is simply by taking and keeping persistent offenders off the streets. A cycle where they are instead simply in and out on short sentences brings most of the downsides, in terms of criminal socialisation inside, but few of the upsides.)

In the context of broader crime-fighting, one obvious way that ministers could focus the police on what Braverman calls ‘common sense, back-to-basics policing’ would be changing or even (whisper it) repealing the laws the police are tasked to enforce. New Labour oversaw an explosion in the number of offences on the statute book, and this trend has not abated since 2010, if the number of high-profile and controversial interventions for alleged hate speech and equalities offences is anything to go by.

A government committed to really gripping this problem could, for example, order a comprehensive review of what those forces with a zero solve rate for burglaries have actually been doing. If much of their efforts have been directed towards goals ministers think unwise – which must be the case if Braverman’s claim that said forces are properly resourced is accurate – it could then take legislative action to narrow their responsibilities and allow them to refocus on what matters.

Unfortunately, it seems to be a golden rule of today’s Conservative Party that with very rare exceptions (such as the Fixed-term Parliaments Act), it simply will not review or repeal any of its legislative inheritance from the New Labour era, resorting instead to tough-sounding but increasingly threadbare rhetoric and playing ineffective whack-a-mole with the symptoms of deep, systemic problems rather than grappling with the deeper problems.

So call me a cynic, but with the best will in the world towards Braverman’s intentions – and more sympathy than many for her frustrations with the British state – I would be very surprised if this initiative delivers a tangible impact on people’s experience of crime, unless followed up by a more substantive programme of reform of the sort this Government seems unwilling or unable to deliver.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.