Theresa May yesterday gave the clearest indication of Britain’s future direction of travel. Her mantra is “Global Britain” – a phrase we will hear endlessly over coming years. The referendum was a vote “to become even more global and internationalist in action and in spirit”, she said.

Certainly, it was good to hear May speak passionately about the power of free trade, not least as the lethally protectionist Donald Trump becomes president of the United States.

But this flies in face of quitting the single market – collectively the world’s biggest economy and destination for almost half of Britain’s exports. Indeed, there was deep irony that May’s speech was in the same venue, Lancaster House, where Margaret Thatcher once extolled this noble concept of unfettered access.

The truth is that for all May’s fine words, there are significant problems with her vision of “Global Britain”.

The first is in the timescale. No one should doubt that sorting out extraction from the European Union and creating scores of new trading arrangements is a mind-bogglingly complex, delicate process with massive consequences

Yet as the clock ticks on Britain’s departure from the European Union, there will be fierce pressure on the Prime Minister to prove her country can stand alone. Already she has been attacked, often unfairly, for obfuscation.

The danger in trying to rush through the kind of deals that will be needed – both with the EU 27 and others – was put to me by a senior cabinet minister recently.

He gave the example of the bilateral trade deal between China and Switzerland. Concluded just under three years ago, it was hailed as the first between the planet’s emerging superpower and a leading Western economy, the culmination of nine rounds of negotiations, starting in 2010.

But while the deal gave 99.7 per cent of Chinese goods tariff-free access to Swiss markets, it was significantly less generous for trade heading in the opposite direction.

Shortly before conclusion of the talks, the chief Swiss negotiator pleaded for a special dispensation for watchmakers selling to their third biggest market, pointing out that China did not produce luxury timepieces.

His Chinese counterpart smiled. “You may have the watches,” he replied. “But we have time on our side.”

Despite Mrs May’s brave talk of dispensing with a deal if it is on the wrong terms, she is the leader needing to find solutions far more than those she faces over the negotiating table. This means she is more likely to grant the greater concessions.

Similarly, Mrs May talked yesterday of ensuring Britain is a world centre for science and innovation, pledging to continue collaboration with Europe. Quite right, too. Yet already such partnerships are fraying following last year’s vote.

Europe may also have other ideas, focusing on internal collaboration rather than aiding a turncoat. Note how a Swiss threat to end single market participation led to the instant severing of academic ties three years ago.

Yet there is a far more fundamental problem with the prime minister’s plan – which is that its vision of a Global Britain appears to be blurred, to put it kindly.

One of the main factors forcing Britain from the single market, and probably the customs union, is not a desire to embrace free trade. It is Mrs May’s antipathy to immigration, fostered in the Home Office and fuelled by last year’s referendum.

To her credit, she has at least made it clear that controlling immigration comes first. This follows her constriction of border controls at the Home Office and her refusal to exclude students from the Government’s immigration cap, to the detriment of both Britain’s businesses and its world-beating universities.

So it is clear, despite promises of some campaigners, that Brexit will not lead to a significantly more liberal stance for migrants from outside Europe.

Mrs May talked also in grand terms about creating a more global Britain “not for ourselves, but for those who follow. For the country’s children and grandchildren”.

Already we hear much talk of the Anglosphere, as traditionalists promote the cause of deeper alliances with the likes of Australia, Canada and New Zealand.

British and New Zealand leaders have talked of a “high quality” deal, with international trade secretary Liam Fox being despatched to Wellington in coming months. Meanwhile, a few glib words from a slippery US president-elect led to huge excitement among Brexiteers.

But if the nation is really focusing on long-term prizes – a sensible idea, given the short-term disruption to business that will follow even a benign Brexit – where is the effort to woo the powerhouses of the future in the developing world?

Not just China and India, important as they are, but the rapidly-growing nations of Africa and Latin America?

Australia, Canada and New Zealand are today worth about $3 trillion, and growing at the same unexciting speed as other mature nations – perhaps 2 per cent over coming decades. New Zealand is smaller economically than Romania, let alone the likes of Argentina, Iran or Nigeria.

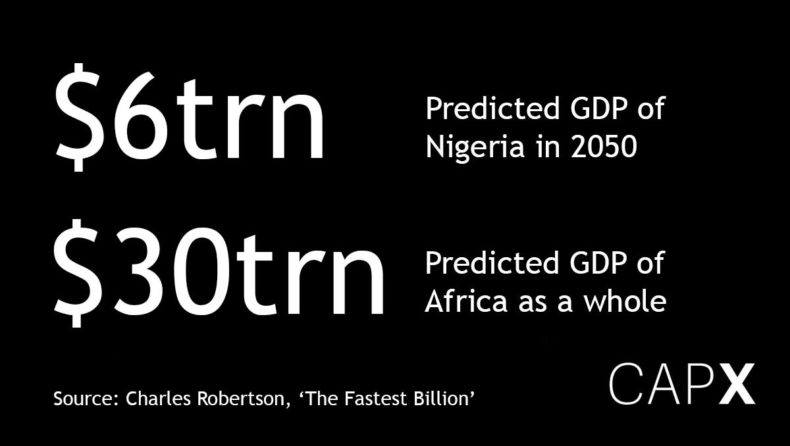

As the economist Charles Robertson explained in his book The Fastest Billion, Nigeria alone will be worth $6 trillion by 2050. The entire African continent – its population due to double to two billion by that date – will be worth almost $30 trillion.

To put this figure in perspective, it is bigger than the combined economies of the United States and Eurozone.

Yet Britain, obsessed with aid not trade, is seeing its share of that growth slip while others from China to India, Brazil and Turkey move in on fast-expanding consumer societies.

This is highly damaging, not least given Britain’s historic links to these areas – the shared language in many parts, the immense soft power of our culture, and even our Premier League football.

Nigerians, for example, are among biggest per capita spenders in our shops – and like several other African nations including Ghana and Kenya, are keen consumers of British education.

Yet from businesspeople to tourists, many Africans have found the costs of obtaining British visas soaring, the hurdles of hostile officialdom rising ever higher, and the consequent attraction of dealing with other nations increasing.

Having been involved in bringing musicians from all over Africa into Britain, I am well aware of visa horrors endured even by some of the continent’s most famous names. And I have heard frequently from middle-class Africans about their disgust at being treated with such disdain by our suspicious system.

So where is the effort to push deals with African countries, despite several being among the world’s fastest-growing economies in recent years? Or a Latin American giant such as Brazil?

Where, in other words, is the focus on the countries and emerging economies that will dominate the future – not just those places that have been our old friends in the past? Where is the recognition that these countries will need access to Britain not just for their goods but for their students and businesspeople, their thinkers and tourists?

If I really thought Brexit would lead to a genuinely global shift in British attitudes, then I would feel far more optimistic about these tumultuous events – and about some of the sentiments in May’s landmark speech.

But the self-defeating focus on immigration limits any sense of a genuine global stance.

If Britain really wants to make the most of Brexit, to truly fulfil the Prime Minister’s promise “to become even more global and internationalist in action and in spirit”, it needs to shed the hostility to foreigners that drove so much of the Brexit debate – and genuinely open up to all corners of a fast-changing world.