Free market economics hasn’t been faring well lately, or so it might seem. Donald Trump rode to the American presidency in part with an attack on free trade, including the synergistic and successful North America Free Trade Agreement (Nafta). Much has been made of a 2016 Harvard poll that purported to show that young Americans reject free market capitalism. And of course, there has been the rise to political prominence of two avowed socialists, Vermont senator Bernie Sanders in the US and Labour Party leader Jeremy Corbyn in the UK.

Are these warning signs that the world’s electorates are swinging back towards a greater support of state interference with markets? Maybe, but a closer examination of the evidence casts a lot of doubt on that proposition.

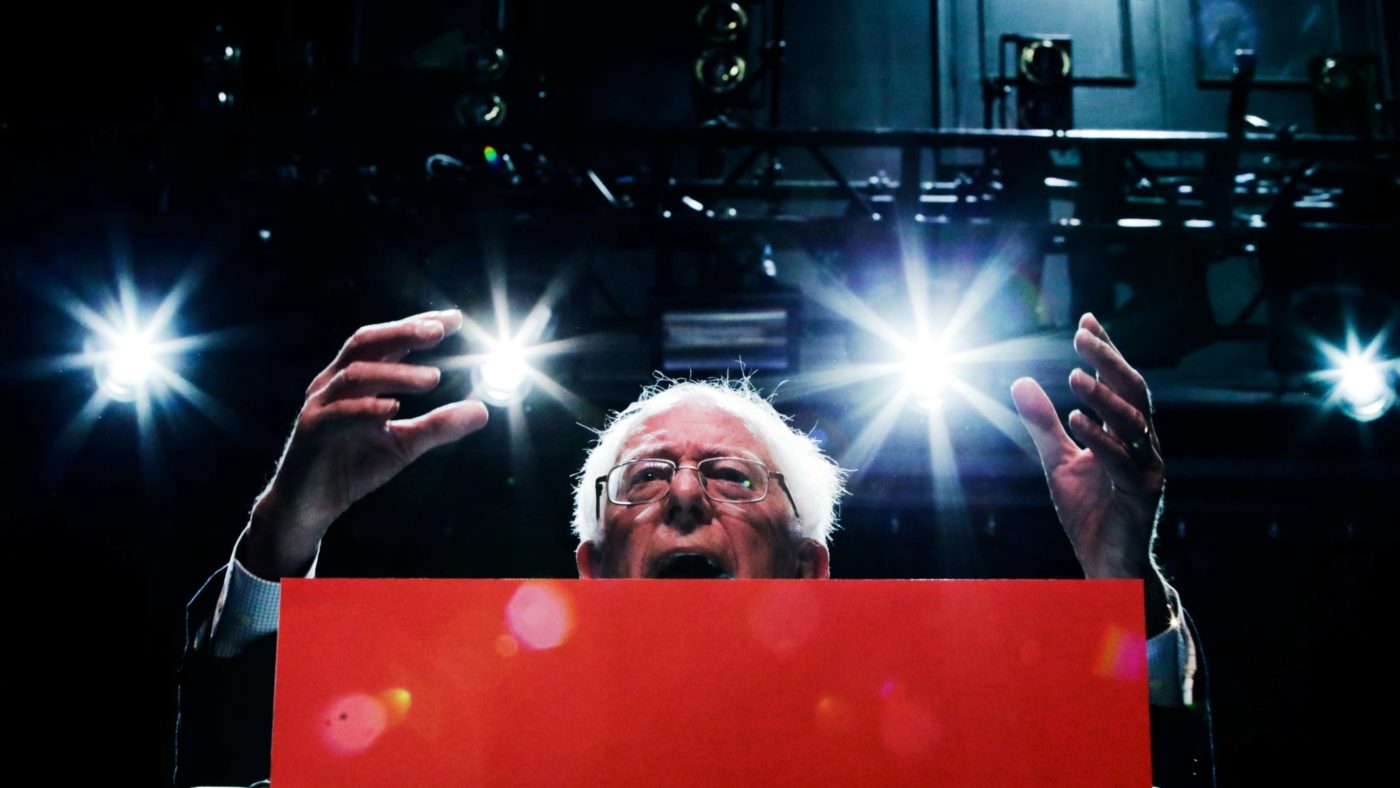

Let’s take the case of Sanders and Corbyn, self-proclaimed “socialists” and trans-Atlantic political buddies. Senator Sanders, who at 75 seems to charm young voters, might have snatched the 2016 party nomination from Hillary Clinton had the Democratic National Committee not rigged the primaries in Hillary’s favour. With Hillary dispatched, he now bids for party leadership. So that indeed sounds troubling to free marketers.

As for Corbyn, Labour’s 2017 manifesto has carried him from non-starter to a level that makes him slightly less unattractive to voters than Tory Prime Minister Theresa May. It looks like he will be around for a while as well.

Socialism is of course antithetical to free market capitalism, so do these successes by two self-proclaimed “socialists” and an American president bent on market intervention reveal a resurgent popularity of government planning and economic management? Is the dirigisme of French Marxist Thomas Piketty gaining ascendance over the free market advocacy of those now-deceased great economic philosophers Milton Friedman and Friedrich Hayek?

Look beyond Britain and America and things don’t seem so bad. Private capitalism has displaced state ownership of the means of production throughout most of the world in the last 40 years. The failure of socialism in the Soviet Union and China was the big story of the 20th Century and won’t soon be forgotten.

No country in the world can be said to practice free market economics in its purest form. Hong Kong was cited by Friedman as a free market paragon and in many ways deserved that honor, but even Hong Kong didn’t have a free market in housing, with nearly half its population living in dwellings provided by the government. Government intervention in the market can be found in varying degrees in all countries where private capitalism is the primary engine of production.

Even in the UK and the US, reports of the market’s demise in the eyes of voters have been exaggerated. It can be persuasively argued that while the rise of political mavericks indeed reflects voter discontent, that unease has been cultivated not in an era of free market capitalism, but rather at a time of radical expansion of government power in the US and a sort of stasis in the UK. The Conservatives have been in power since 2010, but have not meaningfully reformed many Labour creations that date from an era when in was far more explicitly socialist than it is now. Most particularly, the Tories have achieved little reform of the dysfunctional National Health Service.

Markets are always under siege, not only from their socialist enemies but from many of their putative friends, for example corporations that seek government protection from either foreign or domestic competitors. President Trump is responding to pressure from both corporations and organized labour with his rants against multilateral trade agreements. It remains to be seen if the rants will translate into dangerous protectionism.

The Sanders phenomenon didn’t grow out of an era of robber baron capitalism but just the opposite. The Democratic Party’s progressive wing, led by Barack Obama, swept into control of both Congress and the presidency during the turmoil of 2008, dominated policy-making for the next two years and was hell-bent on socializing the American economy. The progressives sharply expanded government control over health care and finance and fell only a little bit short of gaining mastery over that most vital resource, energy.

They spent $832 billion of public money on a “stimulus” designed to strengthen their grip on power and began the process of doubling the national debt. If there ever was a time when free market capitalism was under threat, it was in 2010.

American voters stalled the progressive wave that year by returning the House of Representatives to the Republicans. But there was no immediate undoing of the 2009-10 policies, which retarded economic recovery and provoked increasing voter discontent. In 2016 the Republicans won control of both the Congress and presidency and began undoing some of the Obama damage to the economy.

It can be debated whether Sanders was more radical than Obama or Clinton. At any rate, they and a lot of other progressives were rejected by the voters. The best explanation of the senator’s popularity in 2016 is that he led a children’s crusade. College students took some of the hardest hits in the Obama era. Slow economic growth meant fewer opportunities, college tuition soared because Uncle Sam had taken over the student loan business and was expanding demand. Students could get an education but for many at the cost of huge and demoralizing debts. Bernie promised free tuition, the answer to their prayers even though a totally unrealistic burden on the federal budget, already in deep deficit. Sanders was a product of that old saying: bad policy begets policies that are even worse as people look to the government to solve the problems it created. Sanders’ politics was pretty conventional: big promises.

The same could be said of Jeremy Corbyn. Labour went into something of a slumber after the Tories formed a ruling coalition in 2010. But Prime Minister David Cameron was not able to entirely dispel the discontent that derived from the slowness of the economic recovery, which paralleled that of Britain’s big trading and financial partner, the US.

Real per capita income actually declined in the early years of the Cameron era. Brexit was not a vote against free markets, but a vote for greater market freedom, a reflection of voter unhappiness with the stifling regulatory edicts inflicted by the Brussels bureaucracy. Yet the closeness of the vote and the growing fear that Britain would be hijacked by the exit terms demanded by the EU have been a source of divisiveness.

When Prime Minister May last year unwisely called a snap election to gain support for Brexit, Labour and Corbyn produced a manifesto that even exceeded the promises of Bernie Sanders: reduced waiting times for national health; better fire and police protection; better rail service; no more tuition fees; more national holidays, etc.

None of this matched the old British socialism that Margaret Thatcher put paid to in the 1980s. There was no more talk of nationalizing steel and autos. The proposals to put water and electricity under greater government control were not out of keeping with public utility policies in many capitalist countries.

To a new generation unfamiliar with the socialist stagnation of the 1960s and 1970s, this may have looked like a fresh vision. But most of the politics on both sides of the Atlantic comes under the heading of old-fashioned pie-in-the-sky. It doesn’t necessarily reflect disillusionment with the free market. But it gave Corbyn and Labour a boost in the polls.

A 2015 poll by Reason, an American libertarian magazine, found that 66 per cent of respondents had a negative view of an economy managed by the government, which suggests that the strong voter reaction against the two-year progressive legislative binge of 2009-10 had firm underpinnings. Capitalism, a term that in voters’ minds applies to the mixed public-private system that now exists, had 38 per cent unfavourable rating. But only 21 per cent had a negative view of free markets. The much-publicised Harvard poll had a similar result, which somehow got buried when press coverage termed it a rejection of capitalism.

A Pew Research Center poll in 2014 is a bit out of date but probably reflects lasting sentiments. It found that 70 per cent of Americans believe that people are better off in a free market economy. Germany was even higher at 73 per cent and the UK came in at 65 per cent. France at that time was praising Piketty, but still logged 60 per cent for the free market, and would later elect Emmanuel Macron, who promised to whittle away some market restraints, labour laws in particular.

Most dramatic was Vietnam, where the free market got a 95 percent approval. China scored 74 per cent. And India came up with 72 per cent, an artifact of its modern swing away from stultifying Fabian socialism and towards a new liberal economic order that is finally propelling it towards greater prosperity.

Opinion polls are fallible but there would seem to be ample evidence that ordinary people throughout the world put a very high value on freedom of all kinds, including market freedom. Trump’s trade views to the contrary, that remains true in America. His deregulation successes are highly popular, probably even more so than was the British vote to free itself from Brussels.

The market always exists in some form, and will always exist as long as humans make transactions. They did so informally and often illegally even under the Stalinist and Maoist regimes, which tried to crush markets. The Soviet and Chinese curbs on the market brought poverty and starvation, a lesson well-learned by the world at large.

Markets will often be corrupted by rent-seekers and power-hungry politicians. But are voters down on free markets? It seems unlikely. The Trump-Sanders-Corbyn phenomenon reflects the lasting power of political promises but not a popular rejection of freedom.