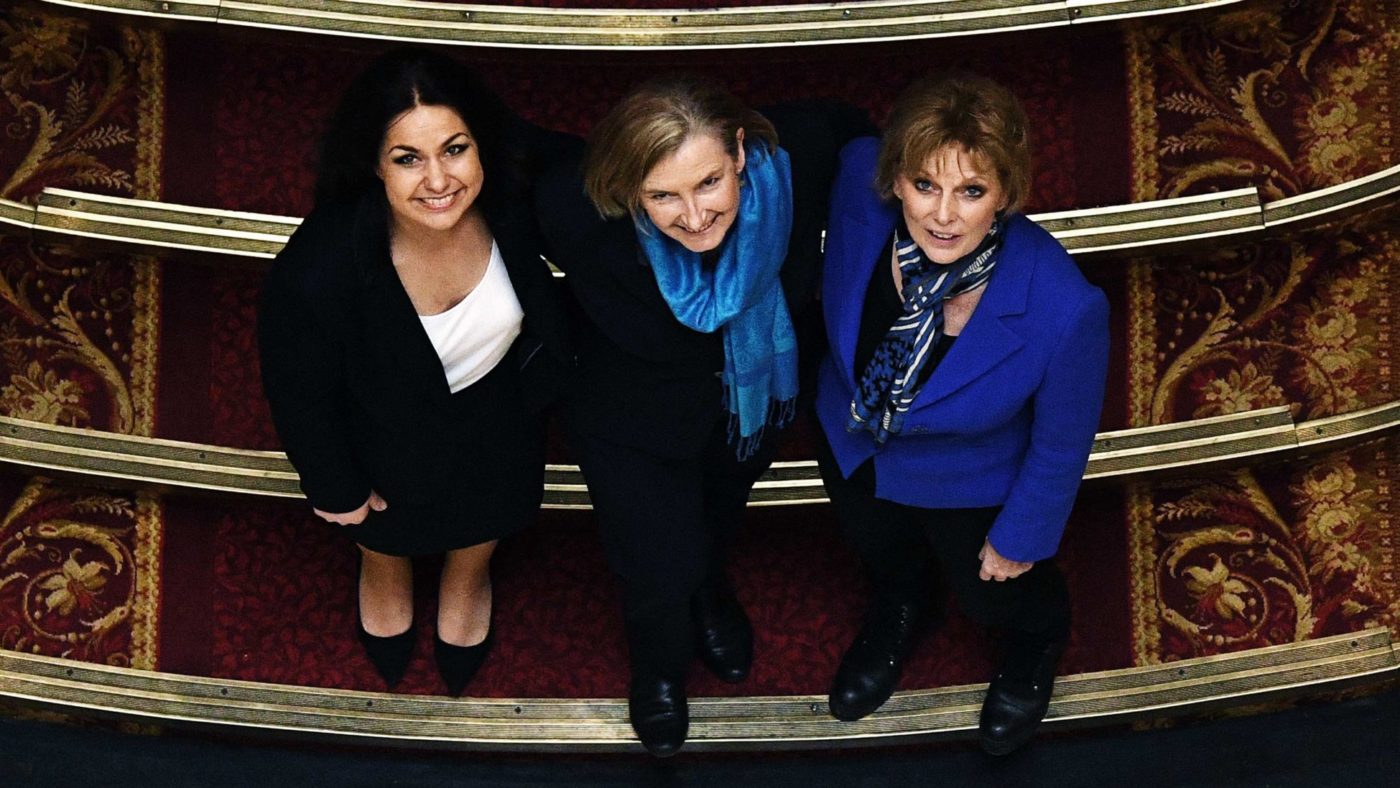

‘Defunct.’ This was one of the many disparaging words used by newly independent MP Anna Soubry to describe the Conservative Party she and her colleagues Heidi Allen and Sarah Wollaston left this week.

In justifying their departure, the self-styled ‘three amigos’ sought to describe symmetrical trends on the left and the right of British politics; just as Labour has been changed irrevocably by the dominance of the far-left, the Conservative Party has been infiltrated by a band of Brexit fanatics. What momentum is to the left, ‘Blukip’ is to the right. Or so we were told.

It would be absurd to deny that for many Conservatives, especially the most ardent Remainers like Soubry, Wollaston and Allen, Brexit has made for a bewildering, disorienting few years, involving plenty of blue-on-blue fire, some of which has been very unpleasant. But does their accusation of a purple momentum undermining Conservatism from within stack up?

The specific claim of entryism has been so thoroughly debunked by Mark Wallace on Conservative Home that there is no point doing the same here. Suffice it to say that there is, quite simply, no evidence of the kind of orchestrated campaign alleged by Souby, Allen and Wollaston.

But what about the bigger picture? Brexit has certainly changed the Conservative Party. But how fundamentally, how irreversibly?

It is telling that while Soubry, Allen and Wollaston claim not to have heard from the Whips office or Theresa May as speculation of their departure grew this week, they all received a text from David Cameron urging them to stay in the party. They are all closely linked to the Cameron project, and, in their resignation statements this week they sought to read the death rites of the modernisation he instigated.

Soubry suggested that ‘within a few months’ of Theresa May becoming Prime Minister, ‘the modernising reforms that had taken years to achieve were destroyed’.

As with infiltration, on this point the evidence suggests otherwise. The flagship modernisation moves are remarkable for the extent to which they have stuck.

Consider marriage equality. The legalisation of same-sex marriage was pushed through by the in the face of much Conservative opposition. Six years on, no remotely ambitious Tory could contemplate anything other than a wholesale endorsement of that policy. Elsewhere, the 0.7 per cent commitment on foreign aid remains intact. The same is true of education reforms and the green agenda.

There are plenty of reasonable complaints about the Conservatives’ direction of travel. But it hardly seems accurate to describe a party using its time in office to splash the cash on healthcare, ban microbeads, declare war on plastic, conduct a race disparity audit and force firms to publish their data on the gender pay gap as lurching rightwards, let alone one that has abandoned modernisation altogether.

But the three MPs now sitting on the other side of the House of Commons chamber cannot see past Brexit. They have decided that the UK’s decision to leave the EU necessarily means an explosion of nastiness, and an endorsement of nativism. And they have therefore convinced themselves that a party that delivers on Britain’s decision to leave the EU is not a party that a one-nation Conservative can call home.

Yet, there is a liberal version of Brexit. (Presumably it was the type Brexit Wollaston supported before she switched from Leave to Remain two weeks before referendum day.) A return of powers from Brussels to Westminster is compatible with pretty much every flavour of conservatism. And the hardline Remainers’ refusal to pursue any outcome other than a reversal of the electorate’s decision has only made the version of Brexit they like the least more likely.

With Theresa May promising not to contest the next election, and a long and ideologically diverse list of MPs looking to replace her, there are few questions more open than what direction the Conservative Party will take in the medium- to long-term. A wide-ranging debate is around the corner.

The irony of the timing of Soubry, Allen and Wollaston’s departure is that they have almost certainly left it too late to stop Brexit, but have absented themselves from the conversation their old party is poised to have not just about its own future, but the future of Britain after Brexit.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.