The increasingly volatile voter is clear; something is rotten in the state of Britain. According to last year’s British Social Attitudes survey, only 40% of respondents believed the current system delivers effective government. A record 45% said they ‘almost never’ trust any party in power to prioritise the country’s needs over political self-interest, and 79% thought Britain’s system of governance could be improved ‘quite a lot’ or ‘a great deal’. Last week, the Director of More In Common reported that focus groups in Beverley, Hull, Scunthorpe and Peterborough were the most disillusioned he’d ever heard; ‘in every group it was anger; despondency or misery about the state of Britain that doesn’t feel sustainable’. One of the respondents – Gary, a sales manager – said he had given up on the system, and that he believed ‘the country almost needs a coup-d’etat’.

Answers vary. For Labour, it was simply that the Conservatives were running it – a theory that seems to have lost favour now that they are in government themselves. Starmer then suggested it might be the fact that ‘too many people in Whitehall are comfortable in the tepid bath of managed decline’, hinting at a recognition that the machinery of government needed to be reformed. Meanwhile, in a recent documentary, Liz Truss agreed with him, putting the blame squarely at the foot of a tangle of bureaucrats that conspired to bring down her policy agenda. Sadly, we won’t be treated to a part two of ‘The Prime Minister vs the Blob’; once he found the Civil Service hostile to his suggestions, Starmer quickly, spinelessly and predictably slithered away from them.

Others turn their eyes elsewhere. The way parliament functions has been described as ‘elective dictatorship’, with too much power concentrated in the executive and too little serious scrutiny from MPs. This creates an institution that acts more like a content mill than a deliberative body, churning outrage and soundbites for a dead-eyed media loop. While power may be hyper-centralised, responsibility is nowhere; ministers reshuffle like Hinge dates, rewarded for loyalty over competence, so policy is made to survive headlines rather than time. Meanwhile, political talent has been inverted: the competent rarely run, leaving a shallow pool of MPs who climb by staffer networks and party loyalty, not competence or vision. Politics has become a dull PR firm with an office-wide drinking problem.

What is clear is that politicians are very much no longer in charge of it all. Increasingly, political questions are solved outside of the realm of politics, with our democratically elected representatives left as little more than bystanders. Take the recent Supreme Court ruling on the legal definition of a woman. Whatever one thinks of the outcome, it was a farcical situation; the result of years of increasing legal complexity secured through lawfare, leading to ridiculous laws being weighted against each other to declare the biologically obvious. But nothing ends here; the decision will be appealed through the European Court of Human Rights, while NHS hospitals are reportedly ‘trying to defy’ the ruling. An even more farcical situation; a foreign court rules on the appropriateness of British law, while arms of the British state refuse to implement the decided law. Starmer sanguinely faces this down with his trademark belief in ‘law’ as an epistemological method.

How has Britain, whose system of government has been copied the world over, ended up in a situation in which the political choices of our elected politicians seem to be constrained to little more than managerialism?

This is something we’re more used to seeing at local government level. If a council changes hands at the local elections, will most residents really notice a radical shift in its priorities? When over 50% of council budgets are spent on statutory duties imposed by central government, will anything really change? How much opportunity is there for change? Decisions come from London, but attention rarely follows; local government amounts to little more than managed solvency.

This is the paradox of ‘shallow sovereignty’: governments appear to rule, but cannot act. Their authority is formal, but not functional. The real answer to Britain’s governing problems is that the decision space – the viable political choices available to leaders – of our politicians is collapsing, constrained by quangos, international obligations, legal activism, bureaucratic resistance, fiscal oversight, activist pressure and the growing social conformity of an increasingly narrow political class.

Decision space is a concept first put forward by Thomas Bossert in 1998 to describe the set of functions and the degree of choice that constrain the decision-making authority in public administration. Bossert’s original thesis addressed three key questions:

- Who has the authority to make decisions?

- What issues or areas are they making decisions about?

- How much discretion or range of options do they have when making those decisions?

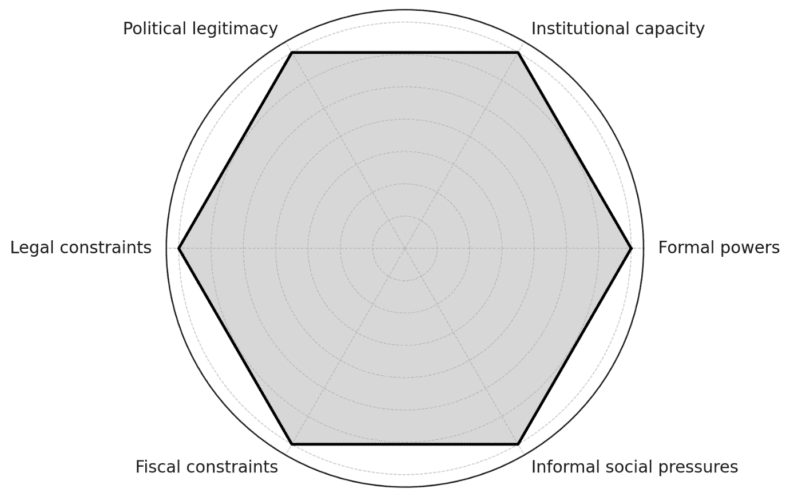

In the political sphere, decision space is defined by the viable political choices available to leaders at any given moment and on any given political issue. It is shaped by a range of factors:

- Formal powers; what it is legally within their direct power/their direct responsibility.

- Institutional capacity; what the state can deliver.

- Political legitimacy; what voters or coalition partners will tolerate.

- Fiscal constraints; what can be afforded.

- Legal constraints; the boundaries set by statute, constitutional convention and judicial interpretation.

- Informal social pressures; the personal cost to politicians who risk professional alienation or social ostracism by advancing unpopular or controversial positions, whether through ostracism from peers and personal networks or attacks by media.

For the sake of diagram, the decision space depicted has five equal parameters. However, in the real world, this is seldom the situation, as one or more of the parameters exert more influence than the others.

.

British politicians face a collapse in decision space on all fronts. The increasing powers of quangos and international organisations has reduced their formal powers; institutional capacity can also be limited from within by bureaucratic inertia and, sometimes, the hostility of the Civil Service, and externally by an increasingly activist judiciary. Fiscal constraints are now far more onerous, due to the increasing informal power of the Treasury and the introduction of the Office for Budget Responsibility. Political legitimacy is now increasingly shaped by a range of campaigning organisations. Politicians are increasingly isolated from the electorate they are tied to, they are drawn from a narrowing range of backgrounds, magnifying the importance of informal social penalties. Finally, with the rise of lawfare, an activist judiciary and increasing obligations as signatories of international treaties, legal constraints have vastly decreased what is legally within their direct power.

To return to Bossert’s original thesis, British politicians increasingly do not have the authority to make decisions, have a reduced number of issues they are able to make decisions about and have a limited range of options when making their decisions. Our democratically elected politicians may be sitting in the driving seat, but they are little more than passengers in a self-driving vehicle which may – or may not – take them to their desired destination.

The answer to Britain’s failing government lies less in the comforting scapegoats of ‘The Blob’ and Whitehall, and more in the disquieting logic of the controversial, anti-democratic philosopher Nick Land. When used by politicians like Truss, ‘the Blob’ becomes a conspiracy theory, little more than a right-wing coping mechanism, whose real function is to mask her own failures in governance. Starmer, despite briefly echoing similar criticisms, has shown no appetite to confront the system’s deeper inertia. But the constraints both leaders chafe against are not solely the machinations of saboteurs; as Land argues, the problem lies in modernity itself, which generates an unstoppable coupling of aggregating complexity and speed that overwhelms political deliberation, planning and control. What appears to be a conspiracy against the governed may simply be a system that no one is yet prepared, politically or intellectually, to overhaul radically enough to make governance feasible again. In the meantime, we are left with the hollow theatre of politics; sound, motion and ceremony masking a stage long abandoned by power. Perhaps, as Thomas Ligotti wrote, ‘if we could hear the silence behind all our noise, we would be driven to madness’.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.