Northern Irish politics is in crisis following the resignation of deputy first minister Martin McGuinness – over, of all things, a renewable energy scheme.

For outsiders to the province, this may seem bizarre. Yet the Renewable Heat Incentive (RHI) scheme is actually a perfect example of a great structural flaw in Northern Irish politics – namely, how the peace process has been marked at times by a shared determination to milk the British state for money.

The “cash for ash” fiasco centres on the local version of the UK-wide RHI project, overseen by ministers from the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP), which shares power with Sinn Fein.

The RHI was intended to bolster usage of renewable energy. But in Northern Ireland, it was implemented without the elementary safeguards that existed on the mainland to prevent people being able to make a profit from the subsidies.

This failure to cap the scheme has led to an incentive to burn fuel rather than conserve it – one farmer is reported to be receiving almost £1 million a year for heating an empty shed. And as a result, hundreds of millions of pounds of taxpayers’ money is set to, almost literally, go up in smoke.

The ensuing drama has left the devolved administration at Stormont teetering on the brink of an early election, or possible outright suspension – which would lead to a resumption of direct rule from Whitehall.

This is because the terms of the power-sharing deal mean that one party cannot be represented without the other: if Sinn Fein refuse to put forward a deputy first minister, the DUP cannot keep the top job.

But the most interesting question is not how two such virulently hostile parties – the political standard-bearers for Ian Paisley’s fundamentalist Protestantism and the Provisional IRA’s outright terrorism – came to fall out, but how they made power-sharing last so long in the first place.

The two parties are still, of course, enemies. The recent collapse in relations is driven largely by the bitter divisions over various matters, including so-called “legacy issues” – especially the fact that several elderly soldiers now face prosecution for killings during the Troubles while minimal progress is being made in solving the many, many crimes committed by the IRA.

Yet what the two parties do have in common – a commonality that has enabled Stormont to survive for so long – is their attitude to public expenditure.

The RHI scheme, for example, appears to have been kept open for weeks longer than it should have been, to facilitate people or organisations getting on board.

The most benign explanation is that the political leaders overseeing the project did not care much about the profligacy involved because they thought London was picking up the tab (which, for once, it isn’t).

This fits a pattern: the main political parties in NI tend to be largely indifferent to the waste of taxpayer funds until it becomes apparent that there will be financial implications for Stormont.

The devolved institutions last came close to collapse in 2015 when Sinn Fein agreed to implement welfare reform, but then reneged on the deal – allegedly because Gerry Adams feared how it would play in the Republic of Ireland if the party was seen to back austerity.

At the time, in one constituency alone – West Belfast, a Sinn Fein stronghold – some 850 families were receiving more than the £26,000 welfare cap.

The DUP was, in that instance, pro-reform. But partly because the government in London had made it clear that if Northern Ireland wanted a more generous welfare system, it would have to pay out of its own budget. Until then, they had not made the issue a priority – not least because plenty of Loyalist working class areas also do well out of welfare.

Fiscal responsibility, in other words, is not a popular political position over here. If you argue, as I have repeatedly done, that the Disability Living Allowance bill in Northern Ireland is disgracefully high – almost 12 per cent per cent of the population are on it, at an annual cost of £1 billion annually – you get minimal political support.

The position of many people is that if that bill was halved, as I believe it could be, it would take £500 million a year out of the Northern Ireland economy.

When he resigned yesterday, McGuinness issued a withering statement in which, among other things, criticised successive British governments for their austerity policies.

It was a staggering comment given the generosity of British governments towards Northern Ireland, in its decades-long bid to counter the impact of IRA terror. Indeed, one of the single most important factors in maintaining the peace process is the way in Westminster has smothered us with cash.

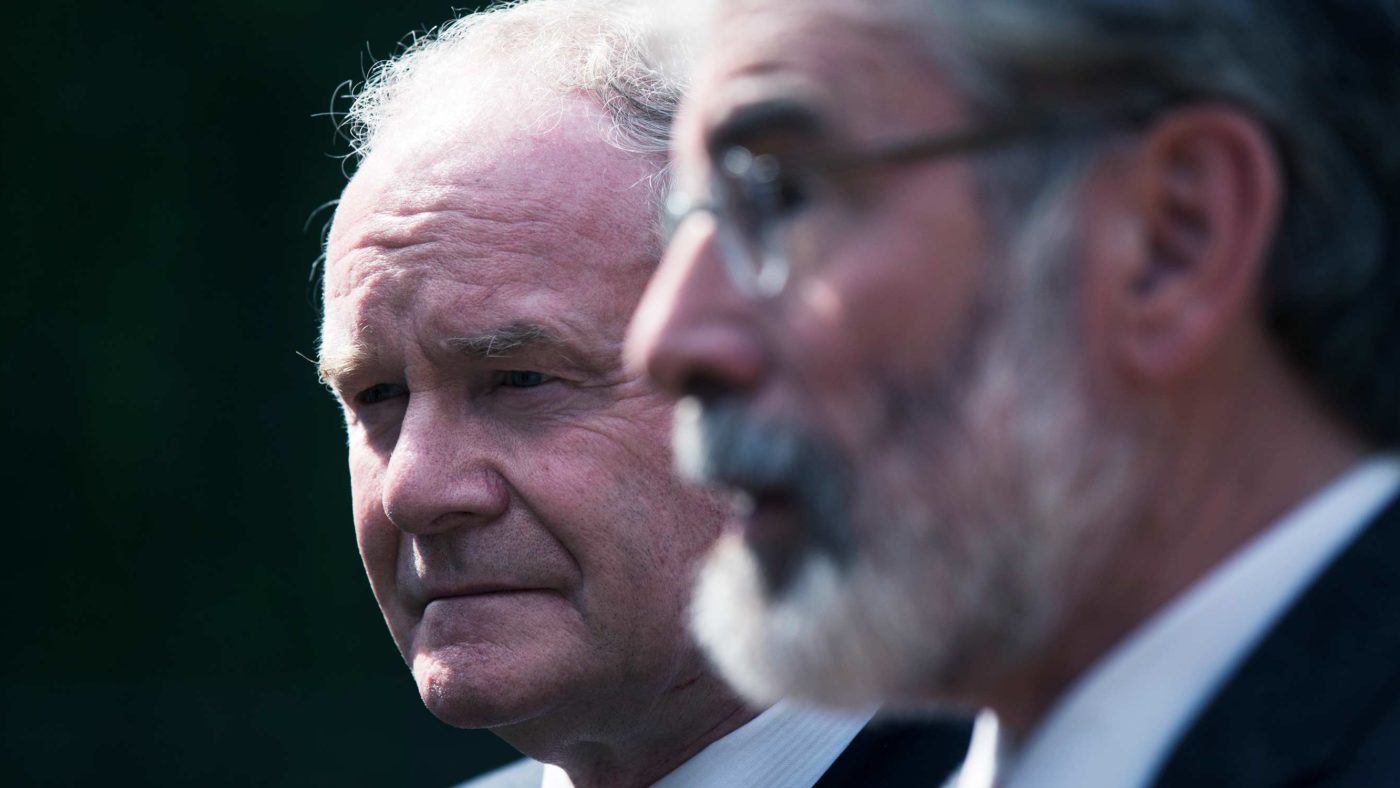

Just after the 2010, the Sinn Fein politician spoke in similar terms about the “huge pain” the Coalition government in Westminster would inflict via its fiscal programme. Standing beside him was the then DUP leader and first mnister, Peter Robinson – who did not seem to be discomforted by that assessment.

How could he have been? His election campaign had led heavily on the “Tory cuts” supposedly advocated by the Ulster Unionists as part of their pact with the Conservatives. That year, the UUP, which once held 11 of Northern Ireland’s 17 seats, failed to win a single one.

As a deprived UK region, and one with such a particularly troubled history, our addiction to public money is understandable. But it does make me increasingly concerned not just about the dependency culture it breeds, but the future of the Union – especially if London eventually runs out of either patience or money.