Now we have left the EU, is Britain going to be a serious state? If we are, then we need to recognise that self-government is not enough. Britain needs to get serious about statecraft.

That means deciding what core capabilities we need as a nation. A serious state would not, to pick one recent example, have blundered into the recent 5G fiasco.

For several years it has been apparent that a breakthrough level of digital interoperability was on the way. This so-called 5G technology is going to have all kinds of implications.

Yet until a Chinese provider, Huawei, came along offering to install the architecture for the new network, those that govern us appear not to have given such matters much thought.

As a consequence, our policymakers were left responding to options that other people put in front of them. They were reduced to making what one might charitably regard as a series of least-worst choices.

But what if Britain had institutions that were capable of blue-sky research and investment? What if there was a government agency able to see the implications of such game-changing technology – and invest in it to make it happen?

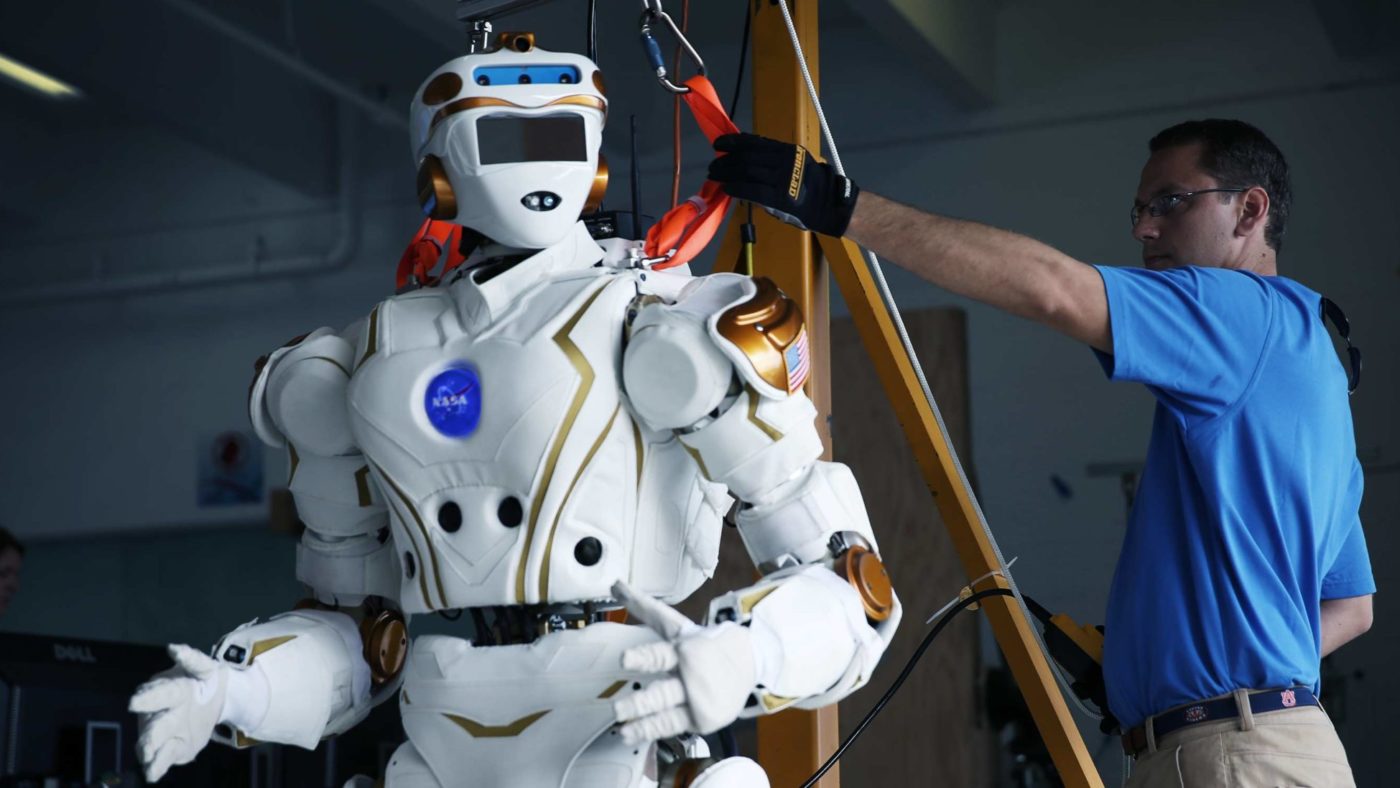

This is precisely what Boris Johnson’s government has in mind. The Conservative manifesto promised a new programme to ‘support high reward research and investment in UK leadership in artificial intelligence and data’. Indeed, plans are underway to create a British version of America’s Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency – or DARPA.

DARPA was created in response to the ‘Sputnik Shock’ of 1957, when the Soviets launched a small satellite into space. Alarmed that Soviet scientists were capable of doing something that seemed precocious at the time, Washington policymakers established a federally funded agency which went on to become DARPA.

It was mandated to make pivotal investments in breakthrough technologies for national security, and to catalyse the development of new capabilities.

Even if most of the agency’s projects over the past half century have failed – achieving neither game-changing advances, nor spectacular spin-offs – it has been behind some remarkable successes. GPS navigation, the micro-processor revolution and aspects of the internet itself were all spurred on by DARPA – and it has certainly helped ensure the US military remains technologically supreme.

But if we are to emulate this pioneering institution, we need to understand why it has worked.

There is a danger here of going down the route of more state intervention. To do so would risk repeating the error that was MinTech, the disaster prone Ministry of Technology set up by Harold Wilson in the 1960s.

Not even the Americans themselves have managed to successfully recreate DARPA formula. In 2009, for example, Barack Obama’s administration launched the Advanced Research Projects Agency–Energy (ARPA-E) to try to stimulate breakthrough technological advances in the energy sector. So far, there is not a great deal to show for it.

DARPA works not because it has omniscient experts, with an uncanny knack for spotting winners and allocating capital accordingly. Talented and brilliant though their project managers may be, what matters is that the continuation of DARPA projects is contingent on being able to get private investors to back what it is that they are trying to do.

Fundamental to the agency’s success is its close association with the venture capital industry. Having to obtain funding from those prepared to risk their own capital is the ultimate reality check on any kind of technological ambition.

If we are to create a British version – let’s call it BARPA – it will have to have a system of hybrid funding at its core.

Nor should those funding decisions be subject to the innovation-sapping peer-review process that prevails across so much public sector research in Britain today. We need a system that allows a punt to be taken on project managers with a vision who can attract private capital to make their ideas a reality.

The Government has promised to significantly increase public R&D spending in next month’s budget. If this extra money is simply channelled through existing institutions, such as UK Research and Innovation, with its group-think, bureaucratic mindset, it is unlikely to achieve very much.

DARPA’s process for allocating funds is competitive and in a sense chaotic – and would be total anathema to Whitehall. For its British counterpart to succeed, it must be as far removed from existing research quangos as possible – physically, culturally and structurally.

Nor should BARPA operate or run labs or research facilities. Like the American original, which only has a small number of employees, it needs to rotate personnel from industry and universities, where most of the commissioned research will actually be done.

It is commonly observed that Britain is good at facilitating science research, but less adept at developing and commercialising it. Perhaps one reason is that those that might commercialise innovation in the UK are not in on it from the outset, and able to take advantage of breakthroughs, as they are in America.

DARPA works not only because it depends on private investors making capital allocation choices, but because changes in US patent law, such as the 1980 Bayh-Dole Act, specifically allow those working on publicly-funded research projects to commercialise the fruits of their work. If people can profit from innovation, there will be more innovation. Significant changes to UK patent law may be needed to enable this to happen.

Innovation is not something that can be engineered from on high. If we want to ensure that Britain has cutting edge technological capabilities – not only in 5G, but in everything from space and AI, to data and gene therapy – government needs to create the conditions that allow it.

Setting up a new agency to encourage technology should not mean being more technocratic.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.