The erosion of the tax base is a big problem. But the erosion of the Government’s poll lead is a bigger one.

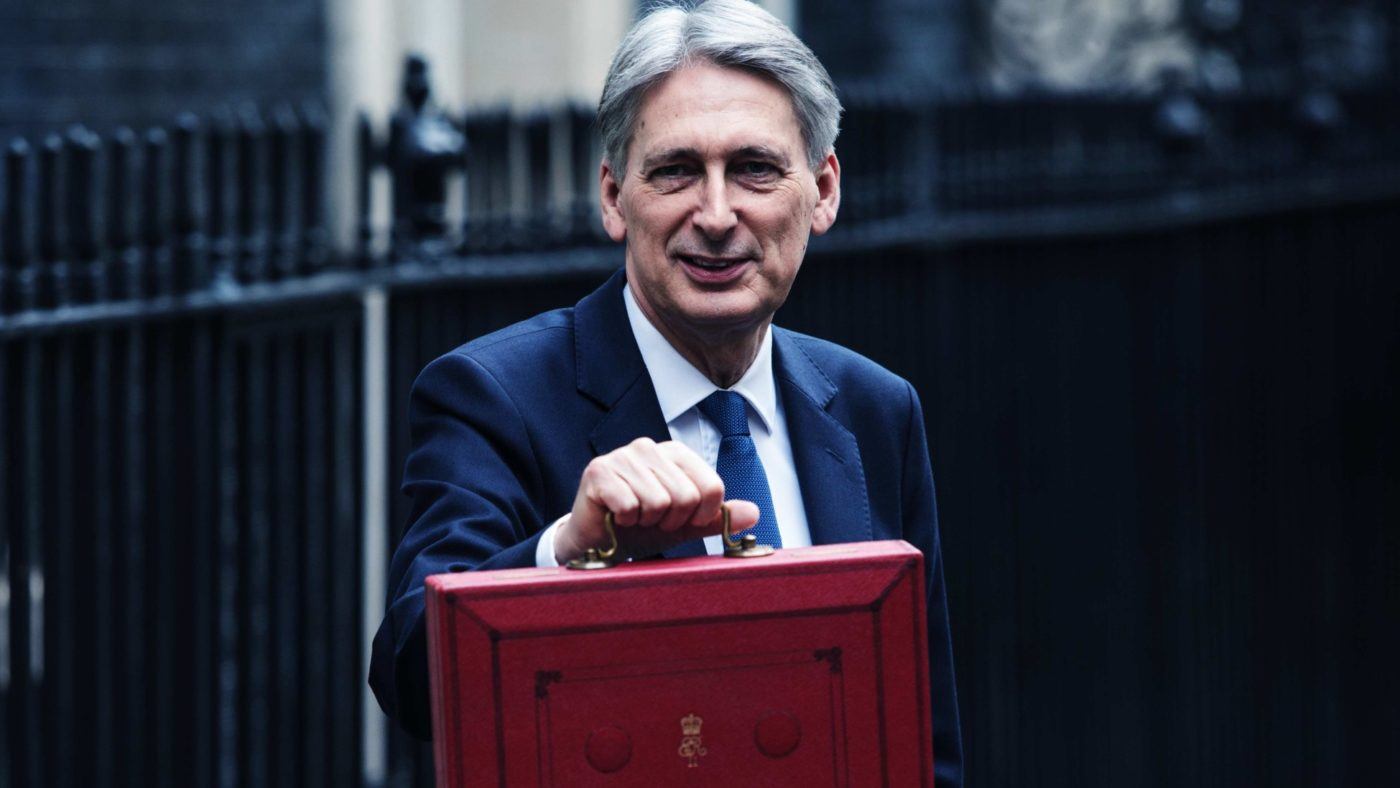

That, in a nutshell, is the explanation for the biggest fiasco of Theresa May’s premiership. Philip Hammond, and presumably the Prime Minister herself, got very worried about people becoming self-employed, or setting themselves up as companies, who really shouldn’t be.

But then they got very worried indeed when this was portrayed not just as an assault on the striving, entrepreneurial white van men who make up the Tory base, but an outright breach of the party’s pre-election promise not to raise VAT, National Insurance or income tax.

So worried that, having told the 1922 Committee of Tory MPs that they would be sticking to their guns, May and Hammond have now reversed track, leaving backbenchers who had been defending the policy irritated and the Budget with a £2 billion hole, to be plugged in the autumn.

Blimey. I've been vigorously defending it… https://t.co/WQKXZYWgaK

— Ed Vaizey (@edvaizey) March 15, 2017

The first lesson of this U-turn is that it confirms what I and others have been saying for a while: that the Government’s sole point of vulnerability is on the Right.

The frankly abject performance of Jeremy Corbyn at Prime Minister’s Questions today, ballooning his shot over the open goal, made it crystal clear that May has absolutely nothing to worry about on that flank.

Exclusive footage of Jeremy Corbyn at PMQs pic.twitter.com/PiTJXIw7Am

— Robert Colvile (@rcolvile) March 15, 2017

Such is the Labour leader’s clod-hopping lack of flexibility, or imagination, that even if the Prime Minister been caught insulting the Queen, Corbyn would probably spend his first three questions passing on the views of Dave from Droitwich who was upset about NHS waiting times.

By contrast, it was agitation among large sections of the Tory party – and Tory-supporting newspapers – which succeeded in bringing this U-turn about. They felt clearly, and to be honest justifiably, that this was a clear breach of the Tories’ “tax lock” pledge.

Never mind that this pledge was originally a desperate piece of electioneering nonsense which David Cameron and George Osborne never imagined they’d actually have to implement, or that May and Hammond rightly disliked the idea from the very beginning. It was a Tory commitment, and it had to be kept to.

But there’s a broader point here, which is that this whole farrago illustrates just how hard it is going to be to complete the work of bringing Britain’s public finances back into order – especially with the looming distractions of Brexit.

Having set an initial target of eliminating the deficit by 2015, the Government is now aiming to do so “at the earliest possible date” in the next parliament. Robert Chote, head of the Office for Budget Responsibility, told MPs this week that you might get to a surplus “by the end of 2025 or thereabouts”, as long as ministers increased tax allowances in line with inflation rather than earnings, an act of fiscal tightening that reduced their value by about 10 per cent.

But then, of course, there would be the countervailing upwards pressure on public spending from an ageing population – and the ever-present risk of another downturn sending the public finances plunging back into the red.

The “tax lock” effectively guarantees that tax rises cannot make a significant contribution to closing the gap between taxes and spending. And on spending, Hammond is already committed to George Osborne’s departmental blueprint, which will see many ministries lose large chunks of their budget, but also ringfences several others.

That’s without factoring the additional costs of Brexit – all those expensive consultants and trade experts to hire, all those European regulatory agencies that need mirroring in British law, all of which are currently intended to be paid for from existing budgets.

But it’s not just a question of fiscal headroom, but political willpower. As Paul Goodman of ConservativeHome has repeatedly pointed out, the structural deficit is moving ever further down the priority list. Since the 2015 election, whenever an issue such as disability benefits or business rates or National Insurance has become controversial, both Hammond and his predecessor have given way.

The reason for this, of course, is simple. With a majority (counting the DUP) of two dozen rather than two hundred, the Tories simply can’t do anything truly radical, or expensive, because too many MPs will get too alarmed.

The odd thing about the NICs decision was that it was, economically, very small beer indeed – the associated cut to dividend allowances, for example, will claw back far more for the Treasury (and there has been surprisingly little outcry on that front). Partly because it did not take the “tax lock” seriously enough, the Government put itself through excruciating political pain for a modicum of fiscal gain.

In many ways, of course, it is far better to get the U-turn out of the way now, rather than once people have started to feel the pain in their pockets: as Hammond said in his statement to MPs, he’s listened, he’s learned, he’s sorry, let’s move on.

It’s obviously good news that we won’t be getting another tax rise. But the danger is that, as well as undermining the Chancellor’s political credibility, this episode curbs any tendency in No 11, or even No 10, towards innovation or radicalism.

At a time when the Labour Party is at its weakest in living memory, it would be a crying shame if the lesson the Government took from this episode is that closing the deficit, or doing any of the other big, bold and brave things that the country needs, is simply too much of a political risk.