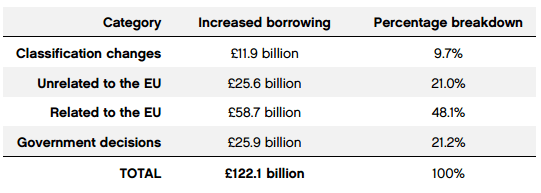

The headline figure of an additional £122 billion of borrowing over the next five years will no doubt have been a source of great concern to many people.

This decline in the public finance outlook since March this year (less than half of which is related to the UK’s exit from the EU) is somewhat concerning.

Debt to GDP ratios are now set to peak at 90 per cent.

One IMF study suggests that median economic growth rates begin to slow above this level of debt. Although the findings of this study have been disputed, there is broader evidence of a negative association between debt and economic growth.

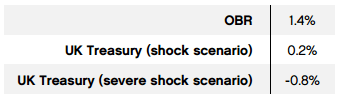

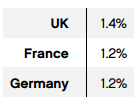

That said, the overall outlook of the OBR’s forecasts is nothing like as pessimistic: economic growth projections are much higher than those presented in the Treasury’s pre-Brexit report and the UK is still expected to grow faster than France and Germany in 2017.

Crucially, the OBR disagrees with the statement that “Brexit-related uncertainty will prompt more aggressive job shedding”.

Breakdown of increased borrowing forecasts:

OBR vs Treasury Growth Forecast for 2017:

Estimated growth rates in 2017:

In a time of economic uncertainty, Hammond was right to ensure that there was no spending splurge at the Autumn Statement.

The Government’s decisions at the Autumn Statement only add £26 billion of spending over five years, which is small in macroeconomic terms.

Hammond’s focus on the productivity rate is also welcome. The UK’s lagging productivity is estimated to be 18 percentage points below the G7 average, according to the Office for National Statistics.

There was a welcome, yet under-reported, commitment to accelerate housing construction on public land. This will go some way to boosting housing construction, but other areas were a missed opportunity.

On infrastructure, in particular, Hammond simply announced further borrowing for investment. There was little consideration of how to incentivise private investment into infrastructure or how to improve the quality of infrastructure coming forward. It is highly questionable whether his £23 billion borrowing for infrastructure programme will do anything to boost productivity.

Overall, however, Hammond’s broader direction on competitiveness of the UK economy appears to be relatively sound. He will push through with the Business Road Map, meaning the UK will have the lowest corporation tax rate in the G20.

And he has recommitted the government to raising the personal allowance to £12,500 and raising the higher rate threshold to £50,000 by 2020. This is needed to counteract the problem of fiscal drag: an estimated additional 1.5 million people were dragged into the higher rate tax band between 2010 and 2015.

Marginal tax rates for those on universal credit will also fall by two percentage points to 63 per cent. This is a major improvement from the days of Gordon Brown, when many low-paid workers faced marginal tax rates over 70 per cent. Of course, the marginal rates are still too high – but this is certainly a movement in the right direction.

It was disappointing that no action was taken on the unilateral Carbon Price Floor – despite there being speculation that it may be scrapped. But the overall direction of travel on tax competitiveness appears to be encouraging.

All in all, a solid and steady start for the Chancellor.