The recessions of the early 1990s overwhelmed Estonia, Lithuania and Latvia. A few years earlier the Soviet Union had collapsed, and with it the economic system that the occupying communist regime had enforced in the Baltic nations. In the span of only two years – from 1991 to 1993 – Estonia’s GDP dropped by 35 percent, while the economic output in Latvia and Lithuania fell by around 50 percent. In response, the three countries introduced an ambitious plan to reform and open up their markets. Flat income tax systems at low rates were put in place; general business-friendly regulations were established; governmental influence on the labour market was minimised.

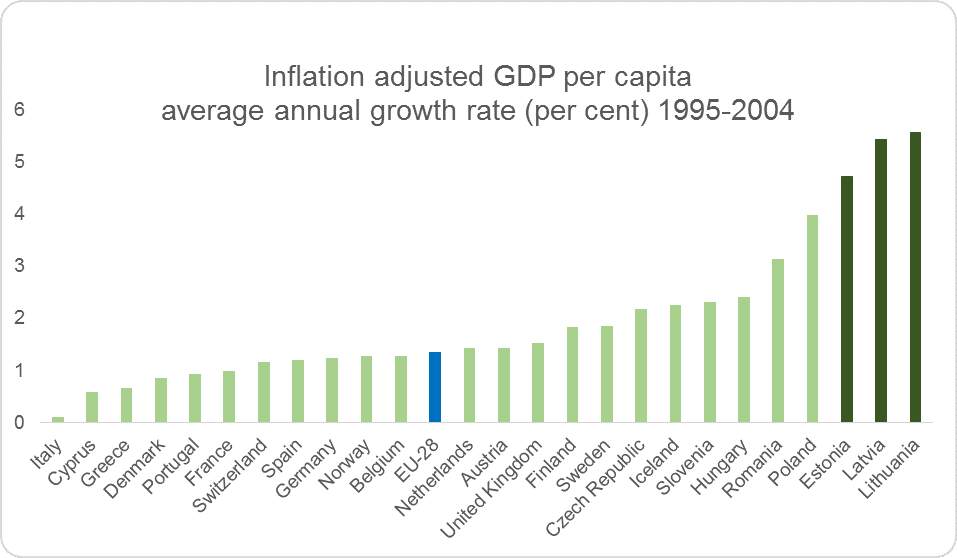

Many economists viewed these changes as a gigantic gamble. The result was a resounding success. The average inflation adjusted growth rate* in the Baltics states from 1995 to 2014 was, as shown in the image below, over 5 per cent, or nearly four times the EU-28 average. No other European country matched this strong performance, driven in part by catch-up and growth-oriented economic policies. But it wasn’t all smooth sailing. In 2008 and 2009, the Baltic states were again hit hard by economic crises. The three nations were particularly sensitive to the global recession, since they had made the decision to maintain fixed exchange rates. Another factor was that foreign investment had contributed strongly to the rapid growth. When the global financial crisis hit, the flow of capital was reversed, deepening the crisis.

In 2010, Latvian GDP had fallen by 21 percent compared to three years earlier, before the crisis had hit. A situation similar to the one in Greece was predicted by many: strikes, populist politics, demands on Europe for economic help, and in the end – bankruptcy and abandonment of the preconditions for joining the Eurozone. But Latvians have a reputation for being a stoic, resilient people. Until recently, their country had been very poor. Few took their newly gained wealth for granted. Hence, elected politicians were allowed to make tough decisions. Rather than taking to the streets, the population accepted the austerity policies.

Still, in 2009 the government collapsed as a result of the crisis, and the centre-right politician Valdis Dombrovskis was elected prime minister. According to the BBC, Dombrovskis “embarked on the toughest budget cuts in Europe: ministries were cut by a third, the number of government-run agencies was halved, and public sector wages were slashed by an average of 25 percent. Some teachers even saw their wages fall by 70 percent.” The BBC further reported: “At the time, the measures were controversial. Some economists accused Mr Dombrovskis of strangling the economy, destroying any chance of future growth. But the Prime Minister told the BBC that Latvia’s economy is now [December 2011] growing again, thanks to those harsh budget cuts. ‘Financial stability is a prerequisite for growth’” the Prime Minister explained.

In the wake of Dombrovskis budget cuts, GDP fell by 18 percent in 2009. In 2010 it was stabilized, and in 2011 it increased by almost 6 percent. Dombrovskis was rewarded for his tough choices, and won two consecutive elections in 2010 and 2011, before the power shifted in 2014. The crises in Lithuania and Estonia were not as deep as in Latvia, but there, too, governments relied on austerity measures that prompted a rapid turnabout. In Lithuania the economy grew by 6 percent in 2011, and in Estonia the economy grew by almost 8 percent. The centre-right government in Lithuania, with its uncompromising austerity policies, lost the 2012 election to the Social Democrats. On the other hand, the Reform Party in Estonia, which strongly favours free market policies, not only got re-elected in 2011, but even gained seats in parliament – an unusual accomplishment among re-elected governments. On the first of March 2015, Taavi Rõivas led the Reform Party to a third election.

The spending cuts were not exactly popular in the Baltic countries. Still, people accepted lower benefits and lower wages. These reforms made it possible to stabilise public finances and at the same time maintain confidence among investors and businesses. Because of lower wages, businesses started to hire new employees even in the midst of the crisis, instead of waiting out the global recession. The above quoted BBC segment opens with an interview with Greta Gorjucko. She lost her job in television, and decided to open a café in the midst of the ongoing recession. Her friends called her crazy – after all, the economy was in free fall. But, explained Gorjucko to the BBC, since wages and prices were allowed to react to changing economic circumstances, there were opportunities for businesses to grow even during the crisis.

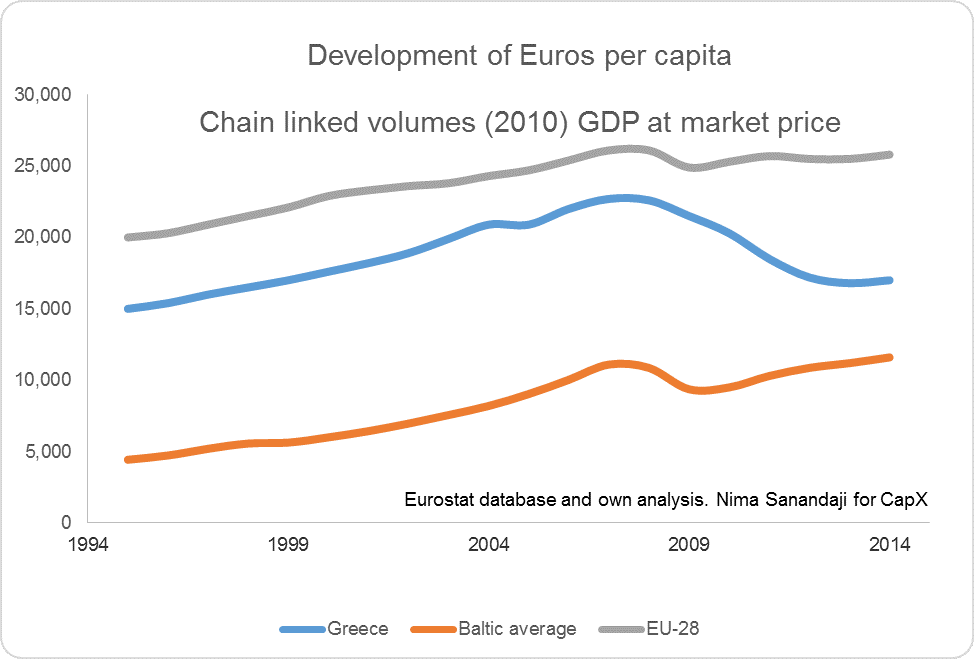

Perhaps the people of the Baltic countries accepted the tough measures because they remembered the harsh times during the Soviet era, the challenges of reforming away from a collapsed planned economy, and the long-term benefits of adopting a modern market system. It certainly helps that their systems promote work and entrepreneurship. People sometimes question if economic policy really affects countries. Isn’t it mainly the whims of global markets that affect how much countries grow? It is difficult to find a more convincing comparison than Greece – which had a relatively favourable starting position in the mid-1990s as a western democracy – and the Baltic states that had just come out of the shock of failed socialism. Whilst Greece chose the path of state interference and populism, the Baltics moved towards free markets and a stoic attitude to public expenditure. In 1995 the Baltic countries on average had merely 83 percent lower GDP per capita than Greece. In 2014, after Greece had faltered whilst the Baltic countries had grown out of their crises, the gap had shrunk to only 19 per cent. Perhaps already in 2016 the Baltic countries will surpass Greece, proving that a generation of hard work and commitment to growth-policies really pays off.

*The chart previously reflected nominal GDP growth rates. The data have been adjusted to show real GDP growth rates.