Food abundance and sedentary lifestyles continue to cause an increase in obesity in countries where these two factors coexist. The hypothesis that this obesity epidemic is related to “bad” food choices is at the heart of many public policies – characterised by swathes of recommendations, advertising campaigns, food pyramids, and nutritional score labels inspired by traffic lights, or primary-school style grades using the first few letters of the alphabet.

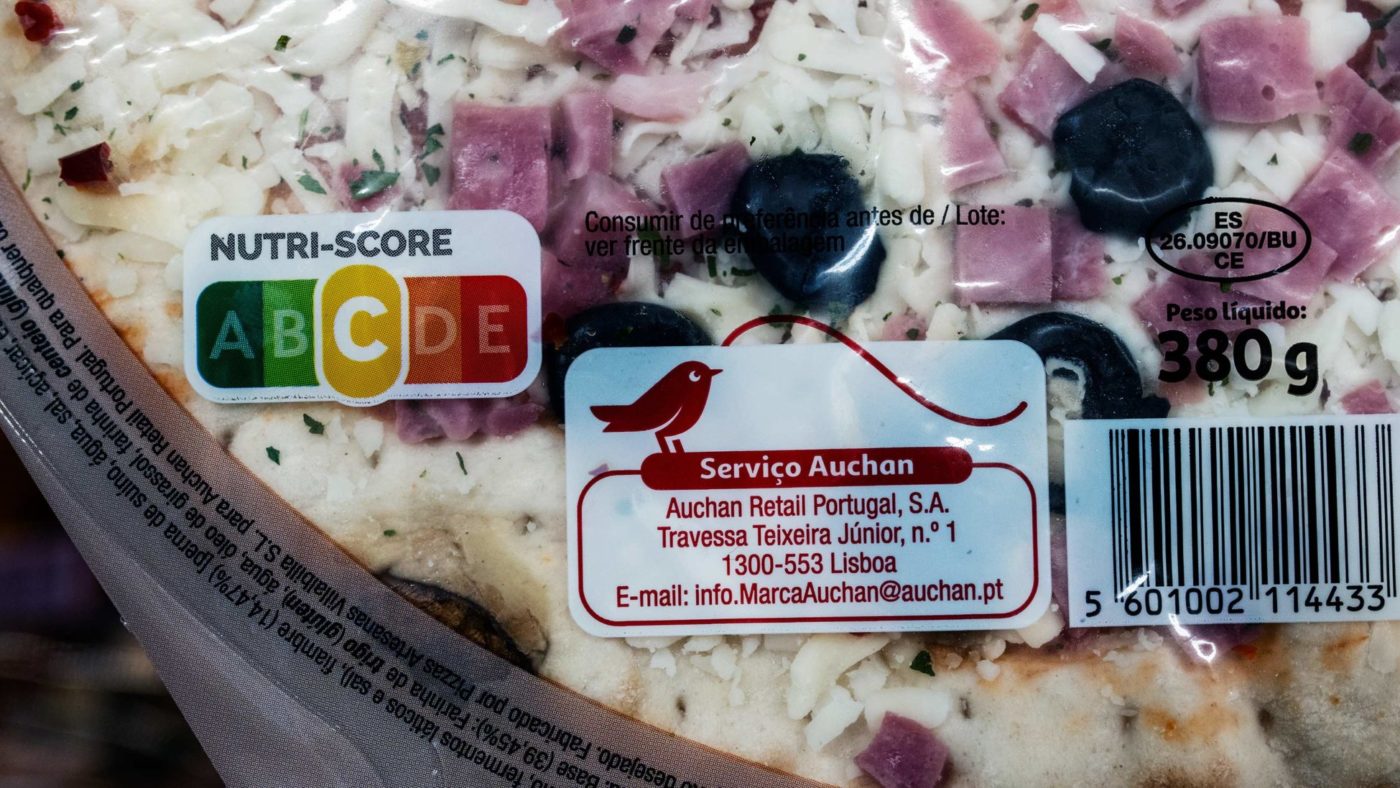

As a result, food packaging is starting to become seriously overcrowded. We now have not just a list of ingredients, but often a host of other mandatory or promotional statements or messages too. In France, the ‘Nutri-score’ was introduced in October 2017, ostensibly to give shoppers better information about what they might be eating.

However a recent impact study reveals that far from being a neutral nutritional arbiter, the score distorts the market in favour of “good” scorers without actually improving the quality of the consumer’s diet.

For instance, if the score is designed to be anti-fat, products that contain it will score low and consumers who take the time to consider this information will opt for a different product. This fact is so obvious that one wonders why certain scores and their aberrant results still come as a surprise to commentators. The reason is that the concept is highly biased.

The first limitation of these systems is their analytical nature: whatever the intrinsic value of the score, it is an evaluation of a product or food removed from any context of daily calorie and nutrient consumption. That is why there is so little value in this type of scoring. For some consumers it can even be an “alibi” where, having made one “good” choice, they go on to make subsequent mediocre ones, believing they can trade off one with the other. It’s the same well-known behavioural pattern of jogging to compensate for smoking – a dangerous fallacy.

The second bias is score blindness for highly processed foods, an especially bad thing at a time when a recent randomised clinical trial has highlighted the obesity-causing nature of such products. Another bias relates to a fundamental principle in nutrition: the substitution principle. This applies to both the processor and the consumer. The former will adapt, so as not to lose market share, and replace fat with carbohydrates most of the time. These will most often be refined starches – hardly a healthy substitute. Consumers who take the scores at face value may unwittingly increase the share of fast carbohydrates in their food intake.

Both of these biases underpin the central shortcoming of nutrition scores. Whether reduced to traffic lights or letters of the alphabet, they are hopelessly reductive. It is illusory to think that a scale of five letters or three colours is giving shoppers an accurate reflection of a food’s nutritional value. The ‘battery’ type score – which takes into account calories, fat, saturated fat, sugar and salt – is more complete. These parameters are presented separately but it’s certainly more comprehensive, if also more complex for the consumer.

Where food labelling differs markedly from what is required for drugs, xenobiotics, and other products is in the lack of requirement for proof of efficacy or harm. Before extending labelling requirements to a score on food packaging, it really is essential to use evidence from quality clinical trials.

That makes it even more surprising that the hypothesis of helping consumers make “better” choices using nutritional scores was put into action before it had been tested – making it little more than a new attempt at anti-Popperian science. Good intentions should never exonerate the promoter from proving the effectiveness of the plan; especially when clinical trials are not convincing.

Several recent data sources suggest serious weaknesses with NutriScore and other behavioural tools. Why is that? Because diet is complex. It is not simply the sum of the NutriScores of the products the consumer has purchased. The amount of food ingested is not measured by the NutriScore, nor are the interactions of foods with each other. Nor does NutriScore measure the way food is then prepared at home. These transformations, particularly thermal transformations, produce different molecules that increase the risk of cancer.

What’s more, NutriScore is blind to the individual genome, which determines the metabolic variations for the same set of nutrients. It also determines the risk of chronic disease. The NutriScore is “one-size-fits-all” , yet the most useful nutritional advice comes from precision medicine.

In the light of this, there is an urgent need for public funding to promote innovation using artificial intelligence and machine learning. For patients, comprehensive bolus analysis, supplemented by clinical and genetic data that are already available, should allow the development of accurate behavioural tools. So far, nutritional scores have not provided any evidence of effectiveness in halting the obesity epidemic.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.