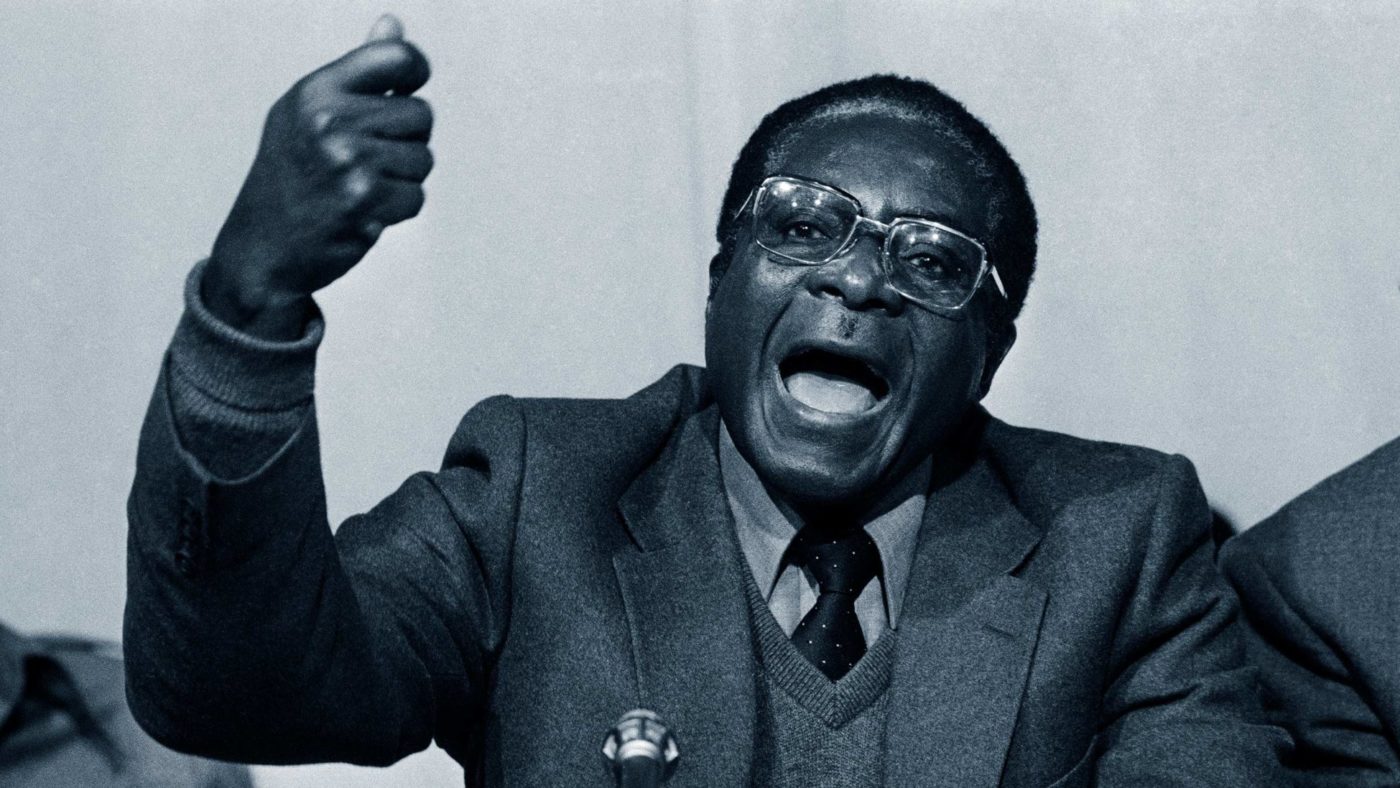

For many people Robert Mugabe’s leadership of Zimbabwe is associated with highly irresponsible fiscal policy, the expulsion of white farmers and a series of events that led to economic collapse and subsequent hyperinflation.

What occurred during the middle period of his 37 years in power is often given greater emphasis than the earlier years when his appetite for absolute power and revolution emerged, and his forces committed unspeakable crimes.

Mugabe’s approach was underpinned by a firm belief that he should be central in the affairs of his country and, consequently, he acted to entrench and project his own power. This is clear from his involvement in the guerrilla war in the 1960s and 70s, his conduct at the Lancaster House conference, and his sanctioning and defence of the Matabele massacre of 1983. Mugabe’s desire to always be centre stage also shaped his subsequent actions as Prime Minister and President, which led to many crises.

Zimbabwean independence arrived in 1980, after 15 years of white minority rule after Rhodesia unilaterally declared independence from the United Kingdom in 1965.

Independence was preceded by 16 years of guerrilla warfare in which nearly 27,000 people died (most of whom were black). The conflict followed a period through the late 1950s and early 1960s of growing tensions between nationalists, in favour of majority rule, and the Rhodesian government. The armed wings of the two nationalist groups that emerged – Zimbabwe African National Liberation Army (ZANLA) and Zimbabwe People’s Revolutionary Army (ZIPRA) – were split across ethnic lines, and were the major forces against Ian Smith’s Rhodesian government.

The government attempted to bring the conflict to a close by arriving at a settlement with moderate nationalist leaders that led to the formation of Zimbabwe-Rhodesia under a new constitution in 1979. The leadership of the new government, led by Bishop Abel Muzorewa (Prime Minister) and Josiah Gumede (President) were denounced as puppets by factions led by Robert Mugabe (who was associated with ZANLA) and Joshua Nkomo (who was associated with ZIPRA) and the fighting continued.

In an effort to reach a settlement and stop conflict, a conference of political leaders Zimbabwe-Rhodesia chaired by Peter Carrington (the then Foreign and Commonwealth Secretary), as it was called in 1979, at Lancaster House where the arrangements for a pre-independence period, an outline for a constitution, and a ceasefire were negotiated and agreed.

When the conference was called Mr Mugabe did not see any need to attend as he was planning a new phase of urban warfare: his view was that a longer war increased the prospect for achieving his revolutionary objectives.

After facing pressure from African president, he attended the conference and is said to have appeared cold, austere and committed to achieving revolution at any cost. He had in exile repeatedly insisted on the need for a one-party Marxist state in which Ian Smith and his ‘criminal gang’ would be tried and shot, and ‘white exploiters’ would not be allowed to keep an acre of land.

He reluctantly signed the agreement after facing pressure from Samora Machel (the then President of Mozambique) to do so, and later remarked, “I felt we had been cheated to some extent, that we had agreed to a deal which would to some extent rob us of victory we had hoped we would achieve in the field”.

As part of the agreement, the UK would send a governor, Christopher Soames, and a number of officials ensure the ceasefire lasted long enough for elections to be held, after which the elected leaders would rule independently.

The election campaign intensified the level of distrust between Mugabe and Nkomo and the political parties they led (ZANU PF and ZAPU respectively), which filtered down to party supporters and the veterans of the guerrilla war. Mugabe was elected to serve under Canaan Banana, a Methodist minister who had been elected President, as Prime Minister in 1980.

He ruled in coalition with Mr Nkomo’s ZAPU: accounts of this report that scarcely a day went by without one side or the other engaging in personal invective. One source of friction was over the activities of ZANLA and ZIPRA guerrillas that had deserted their camps and taken up banditry. Mugabe would criticise ZIPRA (the army wing of Nkomo’s ZAPU) but not ZAPU saying ‘organised boards of ZIPRA followers were refusing to recognise the sovereignty of the government’ and went to say that “if those who have suffered defeat adopt the unfortunate and indefensible attitude that defies and rejects the verdict of the people, then reconciliation between the victor and the vanquished is impossible”.

Six months into his new office he signed an agreement in secret with Kim Il Sung (the then President of North Korea) to have a brigade of the Zimbabwean army (Fifth Brigade) trained by the North Korean Military. This was after Mugabe had remarked that he needed a militia to ‘combat malcontents.’

Groups of ex-ZIPRA ‘dissidents’ (as they were called) roamed Matabeleland – a province of the country in the South West populated by the Ndebele ethnic group, the same group Mr Nkomo was from – holding up buses and robbing stores, and their attacks spread to isolated farmhouses and villages. It is estimated that, even at the peak of their activities, the number of ‘dissidents’ did not exceed 400.

Government ministers, however would portray them as well-supplied and well-organised fighting units and would often exaggerate the level of their activities. In January 1983, the Fifth Brigade was deployed to crackdown on the dissident’s activities, the crackdown lasted until late 1984. Their campaign of beatings, arson, and murder initially targeted former ZAPU and ZIPRA officials, then people chosen at random.

Massacres occurred, and the Fifth Brigade would impose curfews, banned all forms of transport, closed shops, and blocked drought relief supplies for villagers facing starvation. Many of the dead were shot in public executions, after being forced to dig their own graves; many were burned alive in huts; many were shot at random, the largest such incident occurring on the banks of the Cewale River where 62 young men and women were shot, 55 fatally. The International Association of Genocide Scholars estimated the death toll at 20,000.

Mugabe was completely unapologetic, telling an audience in Matabeleland: “We have to deal with this problem quite ruthlessly…don’t cry if your relatives get killed in the process…These men and women provide food for the dissidents, when we get there we eradicate them. We do not differentiate who we fight because we can’t tell who is a dissident and who is not.”

Much more happened after the end of the massacre in 1984: running huge budget deficits plugged by issuance of new currency; overseeing 11 years of decline after 1997 in which the economy lost over 60% of its value; using public money to shore up political support; land reforms in which farms were seized and redistributed; overseeing the second most severe period of hyperinflation in history; and ruling a country with so few prospects that many Zimbabweans chose to seek a better life elsewhere.

Many people, without the means to move, continue to live in dire poverty, with high unemployment, a weak currency, and a highcost of living. It will likely take decades to repair the damage done by Robert Mugabe. He should not be honoured, but nor should the lessons of his brutal rule be forgotten.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.