It seemed to David that the toys in the toy box had been arguing for a long time about the Looking Glass. “We would so like to live in a Looking-Glass house,” said half of the toys. “We want to stay in the real house!” shouted the other half. One afternoon, just before tea David had an idea. “I shall pretend there’s a way of getting through into the Looking-Glass,”, he thought. “I shall announce a referendum. Why, it’s turning into a sort of mist now, I declare! It’ll be easy enough to pretend we can get through—”

The toys had started voting while he said this, though he hardly knew how that had happened. And certainly the glass was beginning to melt away, just like a bright silvery mist.

In another moment the referendum votes had been counted, and David was through the glass. He jumped lightly down into the Looking-glass room. How quickly it had all happened!

As he stood and looked about him he heard a small squeaking, and he turned his head just in time to see The Chancellor of the Exchequer roll over and begin kicking: He picked him up in his hand. He had never in his life seen such faces as the Chancellor made. His eyes and his mouth went on getting larger and larger, till David’s hand shook so with laughing that he nearly let him drop upon the floor. “Oh! please don’t make such faces, my dear!” he cried out, “You make me laugh so that I can hardly hold you! He smoothed the Chancellor’s hair, and set him upon the table next to the Paymaster General who began to talk to him in a frightened whisper. David was a little alarmed at what he had done, and went round the room to see if she could find any water to throw over them.

While he was looking for the water he thought he had better make haste and resign, and in a moment was outside and making a speech without truly knowing what he was saying.

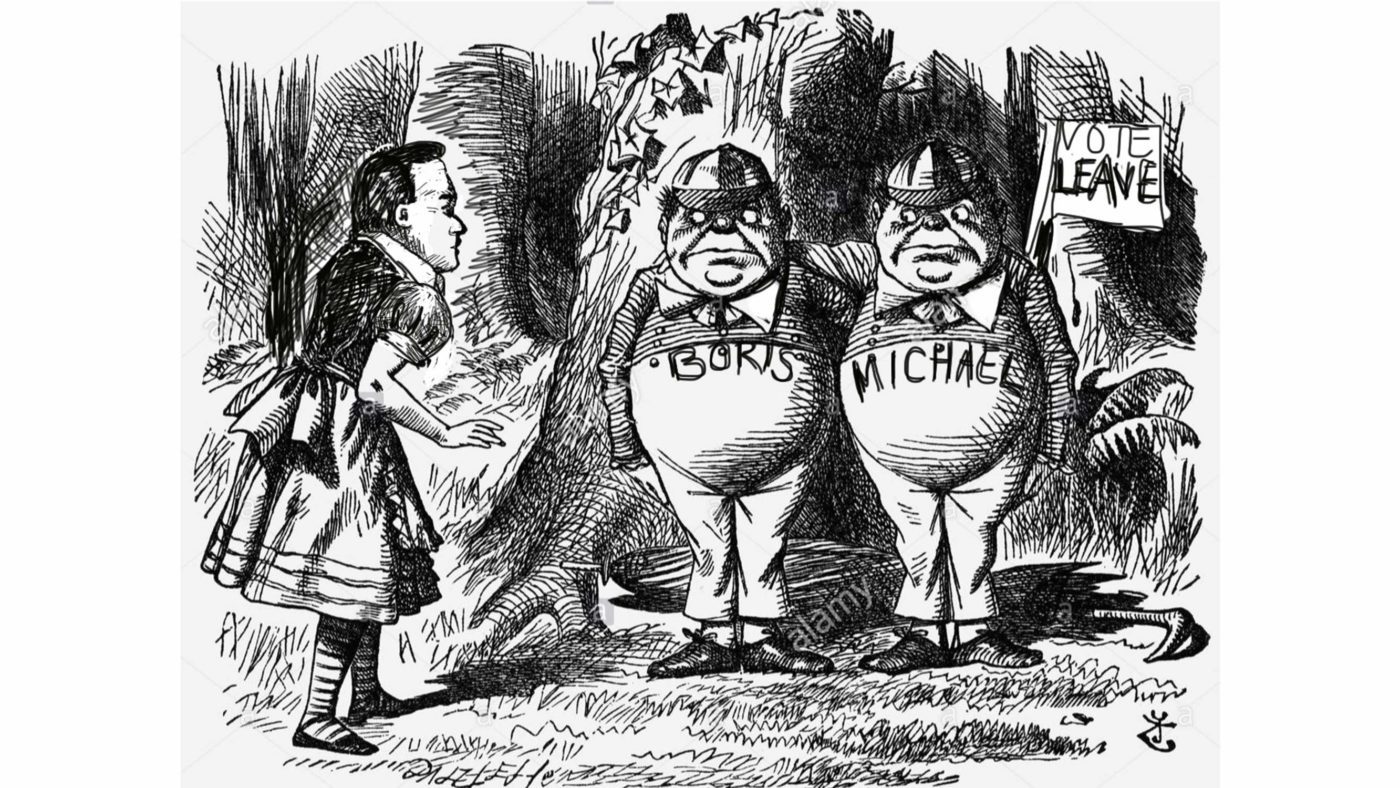

When he had finished talking he floated away and suddenly he found himself in a large garden. He noticed, underneath a tree, the brothers Tweedledum and Tweedledee, only now they had the names “Michael” and “Boris” embroidered on their shirts. As David looked on the two brothers gave each other a hug, and then they held out the two hands that were free, to shake hands with him.

David took their hands and suddenly they were dancing round in a ring. “It certainly was funny,’ (David said afterwards, when he was telling his biographer the history of all this,) “to find myself singing ‘Here we go round the mulberry bush.’ I don’t know when I began it, but somehow I felt as if I’d been singing it a long long time.”

Tweedle-Michael and Tweedle-Boris left off dancing as quickly as they had begun it and before David could sit down they had now began to argue and within a few minutes they had agreed to have a battle.

“I think I must be very brave to fight my own brother” said Tweedle-Michael, in a queer little voice as he tied his helmet tied on.

“I’m very brave generally,” said Tweedle-Boris, who had overheard the remark. Then he hung his head. “But today I have a headache. In fact I have decided I do not want to fight after all,” he said in a low voice.

“That’s all right. There’s only one sword, you know,” Tweedle-Michael said to his brother. “So it wouldn’t have been a fair fight in any case.”

Then it got dark so suddenly that David thought there must be a thunderstorm coming on. “It’s the White Queen” Tweedle-Michael cried out in a high voice of alarm: and the two brothers took to their heels. They were out of sight in a moment and it was as if they had never been there at all.

As they disappeared there was a great noise and the White Queen came running wildly through the wood, with both arms stretched out wide, as if she were flying. “But I’ve got children,” she cried, “I’ve got children and she hasn’t!”

“Who hasn’t?” asked David.

“Why the Blue Queen of course,” shrieked the White Queen.

“Of course” said David, feeling very much inclined to laugh. At that moment the White Queen tripped up.

“Take care!” cried David. But it was too late. With a great scream the White Queen had fallen over.

“I didn’t say it!” she cried to David.

“Say what?” he asked.

“What I just said,” replied the White Queen with a smile. And she dabbed at the blood leaking from her head.

“Why don’t you scream now?” David asked, looking at the blood and holding his hands ready to put over his ears again.

“Why, I’ve done all the screaming already,” said the White Queen. “What would be the good of having it all over again? Consider what a splendid person I am putting the Country first like this. And now here she comes!”

The White Queen spread her arms and flew off again.

There was an enormous clattering of hooves and the Blue Queen came riding through the wood, surrounded by knights, all of them on horses. She pointed at David with a long finger.

“That boy has my crown,” She cried out, and straight away two knights came towards with their clammy hands. “Give me my crown!” She ordered him.

David didn’t see why she should be the only one giving orders and thought he would try it for himself as an experiment. “I order you to take my crown!” He said sternly, adding, “Your Majesty,” out of politeness, and made a small bow. And as he watched the Blue Queen take his crown David found himself floating away. He felt lighter than a feather, and the noise from the garden seemed funnier to him than anything he had ever heard.

He sang himself a sort of un-tune as he floated away. “Doo-doo, doo-doo.” Knowing it was not much of a tune he added “Right,” for good measure, and then “Good.”

“What a funny day”, he thought. “I wonder what the future will hold?” And then he stopped and thought about that and it seemed to him that the future did not exist any more than the past.

“After all, I was the future once,” he said.

How it happened, David never knew, but exactly as he said these words, he was gone. Whether he vanished into the air, or whether he ran quickly into the wood there was no way of guessing, but with a feeling of applause ringing in his ears, just as quickly as it seemed he had arrived, David Cameron was gone.