There is a paradox in the fierce criticism of the House of Lords by some members of the government in the row over tax credits. The rather thin grasp of history of some of the critics ignores the original cause of the 1911 crisis. It was the attempt by the Lords, on largely selfish grounds (land tax and income tax on extremely highly paid people) to reject the very popular “People’s Budget” of 1909, introduced by Lloyd George with the following words:

“This is a war Budget. It is for raising money to wage implacable warfare against poverty and squalidness. I cannot help hoping and believing that before this generation has passed away, we shall have advanced a great step towards that good time, when poverty, and the wretchedness and human degradation which always follows in its camp, will be as remote to the people of this country as the wolves which once infested its forests.”

It was the first ever redistributive budget designed to help the poor, so it is ironic that the current row is almost that in reverse, with the Lords defending 3.2 million largely working poor from financial harm, from a Budget measure that will in the medium term cause serious distress. Then the Lords were defending a distinctly unpopular position. Now the boot is on the other foot.

People also forget that the crisis was precipitated because the Lords were, even in 1909, forbidden from amending a Budget. They had to accept or reject it altogether, and it was the initial rejection that initiated the crisis. They only allowed the Budget through when the land tax had been dropped. In those days the Lords was dominated by a single Party, the Conservatives, who themselves were dominated by large landowners, again the opposite of the much more diverse Lords today.

Today it is the Commons that was denied the opportunity of amending the measure, because the government chose to put through a massive social welfare reform by the means of a statutory instrument. Neither can the government really claim that there were earlier opportunities to reform the measure. Until the relatively recent IFS analysis, the Treasury had led everybody to believe that the measure was neutral for the working poor, a circumstance that will at best only come true in five years’ time.

It is that choice of a statutory instrument that has given the Lords the right to reject or defer the policy, precisely because of the government’s handling the hands of the Commons. In truth this clash is more between the Executive and the Lords, rather than between the Commons and the Lords. And the Lords is carrying out its historic function, asking the Commons to think again. Had the Commons been given a proper chance to think in the first place this circumstance would never have arisen.

As a result the rather bullying response of the Government is seriously unwise. It is already the talk of the Commons that at least 40 MPs have been cajoled or coerced into dropping their opposition to this measure. I do not know the truth of this, but it is certainly true that a very much larger number are worried by it, and are hoping that the Chancellor will find a way to eliminate the penalties for the poor. In that context the government is extremely unlikely to be able to deliver on its threat to reform the Lords.

Remember that attempts by governments to seriously reform the Lords in recent years have tended to come seriously unstuck, most spectacularly the Coalition’s rather shabby attempt a few years ago. The only serious exceptions tend to be modest amendments by governments (like Tony Blair’s) with very large majorities.

An attempt by a government with a majority of 12 is fated to fail. This is doubly true if the tax credit policy goes ahead. From December through April there will be a howl of anguish as the losers realise the consequences, and MPs feel the backlash in their constituencies. I am not talking here about electoral consequences – although they may follow in local government elections – I am talking about the impact on the consciences of ordinary decent MPs as they struggle to advise hard working families whose household budgets have become impossible.

Against that context the moral authority of a government to force a reform of the Lords will have evaporated. Similarly the threat to flood the Lords with Tory peers is technically possible, but hard to imagine being carried through in practise. The last Honours List was not exactly received with acclamation, packed as it was with ex-advisers. Quite how an inevitably tawdry list of hundreds would go down, I do not know, but it would likely be viewed as one of the biggest acts of constitutional vandalism in modern times. And that is likely to be the view both of contemporary commentators and historians.

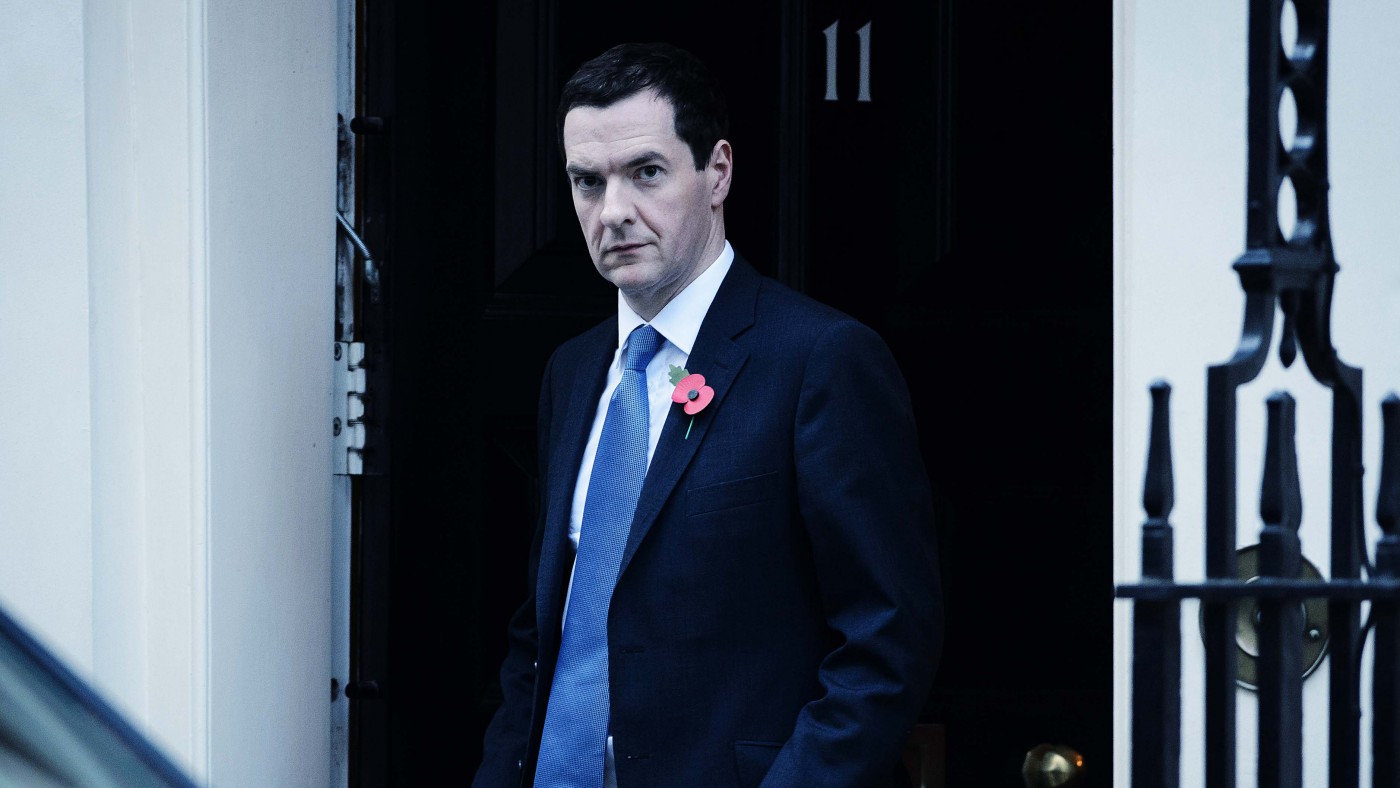

This has of course the effect of throwing dust in the eyes of the public and the commentariat about the real issue, the impoverishment of working families that we are all supposed to support. That is where the efforts should be centred. Nobody should pretend that the Chancellor’s job is easy in that regard. Revising this choice will mean we have to take other hard choices, but that is why he is there.

So if I were advising the Lords tomorrow, I would argue that they should support either the cross bench motion or the one in the name of the Bishop of Portsmouth, both of which effectively ask the Commons to think again, but in more emollient (and less fatal) language than the Liberal and Labour motions. As for the government, I would calm down the debate, listen carefully to the cross Party motion in the Commons on Thursday, and think again.

I do not believe for a moment that the government intended to produce a policy that delivered such agony to so many decent people. It is in absolute defiance of the excellent speech of David Cameron at the Conservative Party Conference, espousing our One Nation traditions. So let us recognise that it was a mistake, remember that the strongest stance is often the one of most flexibility, and thoughtfully and carefully put it right. If the government does that it will earn enormous credit from the vast majority of the British people.