Intriguing reports are circulating that the Government is going to cut stamp duty. The Centre for Policy Studies has long been arguing that this makes overwhelming sense – with one big proviso. Here’s why.

First, stamp duty – as our report Stamping Down shows – is not just an unpopular tax but a very bad one. It makes it harder for people to move, which in turn contributes to the massive misallocation of housing in this country.

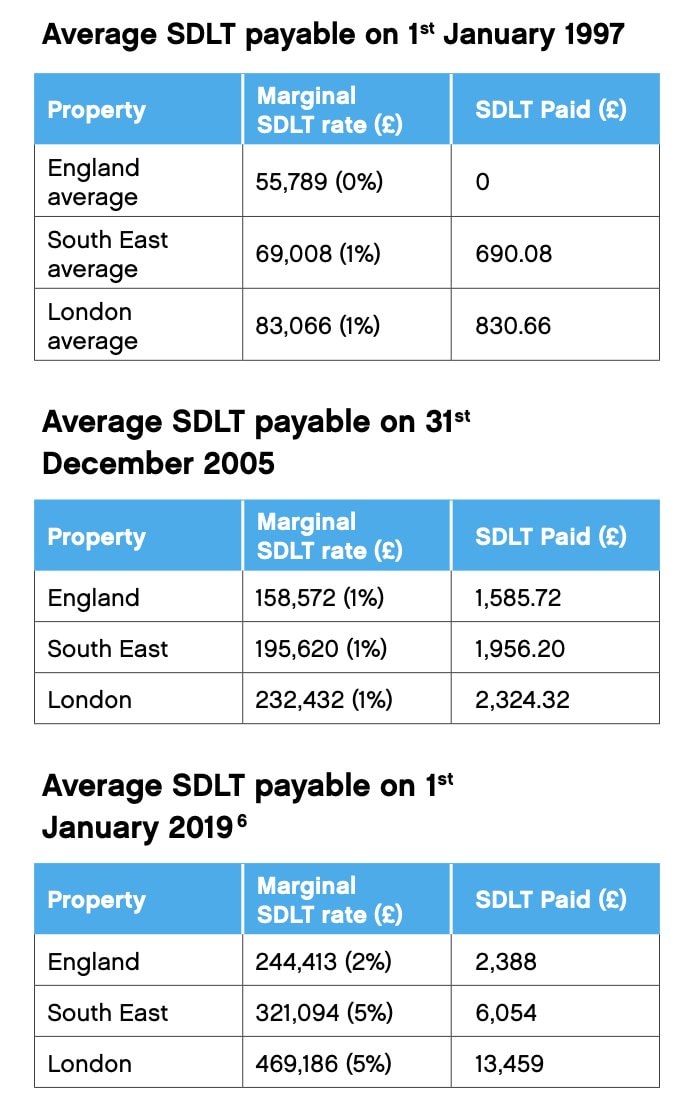

It is also a relatively new tax. As recently as 1997, it was just 1% of transaction costs. Today, the average home in London and the south east pays a marginal rate of 5% – though that can reach 12% for the most expensive homes and 17% if they’re going to foreign buyers. In 2005, the median amount paid was £1,585 in England and £2,324 in London. By 2019 that was roughly £2,400 and £13,500. It will be even higher today.

.

This obviously falls overwhelmingly on the areas where house prices are highest. London and the south east are responsible for 30% of transactions but 60% of stamp duty receipts (again, as of 2019).

Now, you might say this is a good idea. House prices have grown enormously and the Government should capture a slice of that unearned wealth to fund public services, Russian oligarchs should pay up for their London mansions, and so on. But in fact stamp duty has long past reached the point where it’s actively distorting the market. George Osborne hiked it to the point where the amount of money coming in has actually fallen significantly (which does coincide with Brexit, but was starting to happen before it). The cost of houses, and of moving, means people are moving less often. According to Savills, people are now moving house half as often as they used to before the 2008 credit crunch – from around four times after their first purchase, to two.

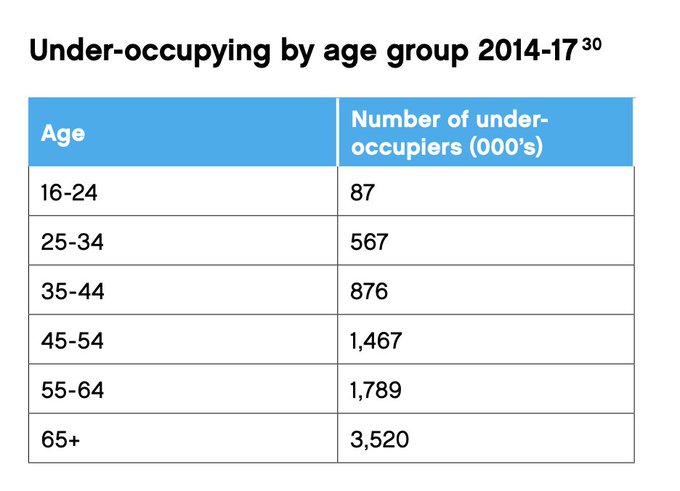

That in turn contributes to the misallocation I mentioned earlier. Partly because it’s harder to move, lots of people (especially elderly people) end up living in homes that are too large from them. From 2014-17, 3.5 million people over 65 were under-occupying their homes – again, that figure will be higher now.

.

In short, stamp duty isn’t just affecting ‘the rich’. It’s helping to gum up the entire housing market. Cutting it would be both popular and sensible.

But, I hear you ask very loudly, won’t this simply drive up house prices yet again, even further? I’m glad you asked!

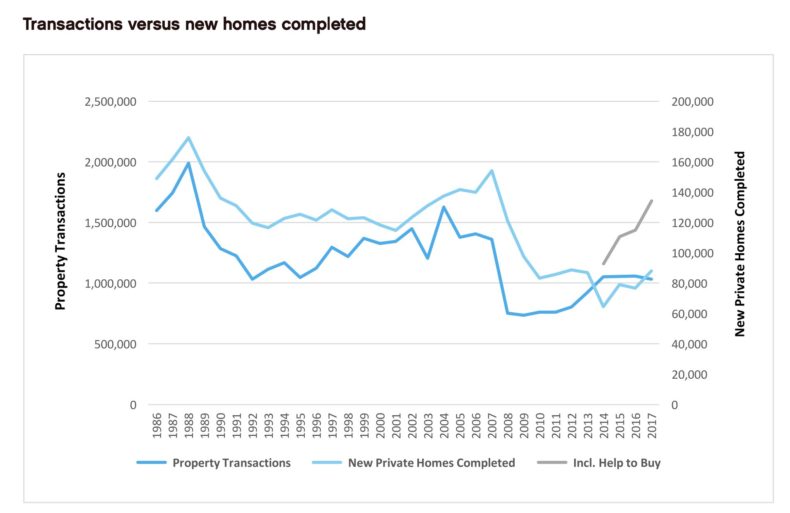

A crucial point – which is known to everyone in the housing industry but absolutely no one outside it – is that the number of houses we build in this country has an incredibly close relationship to the number of times people buy and sell houses. This should be unsurprising. If people are buying and selling houses, it sends a powerful signal to housebuilders that ‘if you build this thing, you can sell it’.

.

The main effect of the Government’s Help to Buy scheme (the grey line on the chart) was that it effectively spoofed this signal, substituting a guarantee that people would want to buy what you were building for those traditional market signals while transactions were low. What this means is that if you can drive up transactions (by cutting transaction costs, i.e. stamp duty), you can drive up housing supply – one new build for every 8.5 transactions is the rough historic ratio.

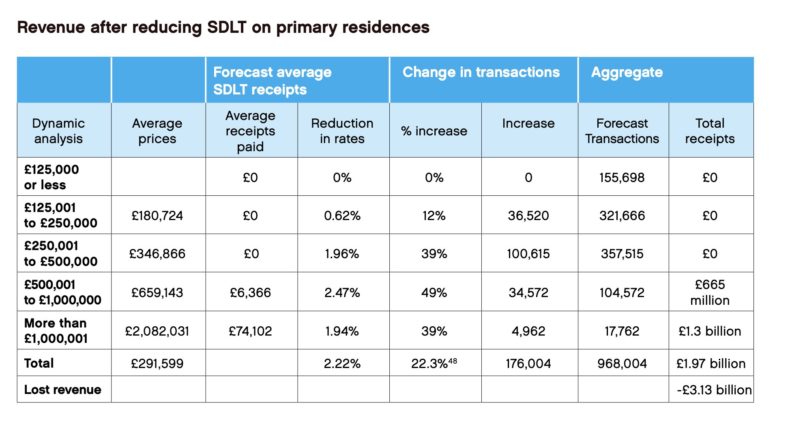

And this also makes cutting stamp duty much cheaper. More transactions means more revenue. More houses being built means government needs to spend less on housebuilding. The CPS estimates that the costs of both slashing and abolishing duty are much lower than the headline rate. Some excited property industry analysts have even pointed out that if you accounted for the extra fees for estate agents and solicitors, and the slice the government takes in tax, you could actually make a case that revenue would increase.

.

But this only works if that market signal transmits itself – if the increase in transactions leads to builders going ‘right ho, we’d better build more because there’s more appetite for our product’. And of course we don’t live in that beautiful world in which supply for housing can match demand. We live in a world where politicians pretend that you can get all the homes you need in places where no one need see them, while protecting Our Precious Green Fields.

So yes, we need to cut stamp duty – we suggested it should be abolished altogether up to £500k, 4% from £500k-£1m, then 5% above that (with an extra surcharge for non-resident foreign buyers, and maintaining the surcharge on second homes). Another welcome move would be to shift responsibility for paying stamp duty from buyers to sellers. Economically it doesn’t matter either way, but it would make a huge difference psychologically. The downside is this would be very unfair to people who have bought houses recently.

Alongside any reforms to stamp duty, we need to at the very least maintain and ideally increase the supply of land for development, in order to ensure that any cut doesn’t simply increase demand for the existing supply of houses.

P.S. If your response is that we still need to capture more of that unearned housing wealth, then a council tax revaluation to move away from 1991 valuations is a much fairer and less distortive way to do it (though not exactly popular either).

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.