“Comprehensive schools have largely replaced selection by ability with selection by class and house price.” These were the words of the Labour education reformer Andrew Adonis in 1998. And two decades later, selection by house price remains just as prevalent within the UK’s education system, if not more so.

A recent study by Teach First suggested that there is now a 20 per cent premium on house prices in areas surrounding top comprehensive schools. Estate agents are even capitalising on this by running special search engines that allow families to find properties within the catchment area of good or outstanding schools.

So how can we tackle selection by house price? Encouragingly, it appears that the new crop of free schools established since 2010 are playing their part in widening access. Not only are such schools more likely to be judged good or outstanding than other state schools, but the proportion of pupils eligible for free schools meals is higher than the national average – and according to the New Schools Network, free schools are 10 times more likely to be located in the most deprived local authorities compared to the least deprived.

But might it be possible that grammar schools could play a role in tackling educational inequality, too?

This idea is deeply controversial. Critics argue that the old system of grammar schools and secondary moderns left many children behind. And the Government’s plans to expand provision have inevitably been criticised as benefiting bright, middle-class pupils at the expense of the rest.

The key thing to understand, however, is that today’s education environment is not that of the old days, with the black-and-white division between grammars and comps. The creation of academies, free schools and University Technical Colleges has introduced choice and competition into the system at many levels. This, together with the longstanding faith school sector, means that there is a diversity of choice for parents which would remain unaffected by the promotion of new grammar schools.

And despite criticisms that grammar schools leave the poor behind, the evidence from London boroughs that allow selection by ability shows that it can be compatible with higher educational standards for all.

The capitals’ selective boroughs have very different socio-economic characteristics: some are economically deprived and have large numbers of ethnic minorities attending secondary schools (Redbridge and Enfield, say); some are economically deprived and have a majority of white British pupils (Bexley), while others are in the more prosperous suburbs (Bromley and Sutton).

But the common denominator is that schools have seen dramatic improvements in recent years (apart from Barnet, where performance was already stellar). The overwhelming majority of pupils are now attending good or outstanding schools.

The lesson here is that grammar schools do not have to exist at the expense of other schools.

This is not to say, of course, that there is not a pressing need to increase access for disadvantaged pupils into grammar schools. At present, only 3 per cent of grammar school pupils are entitled to Free School Meals, compared to 16 per cent of pupils attending non-selective schools.

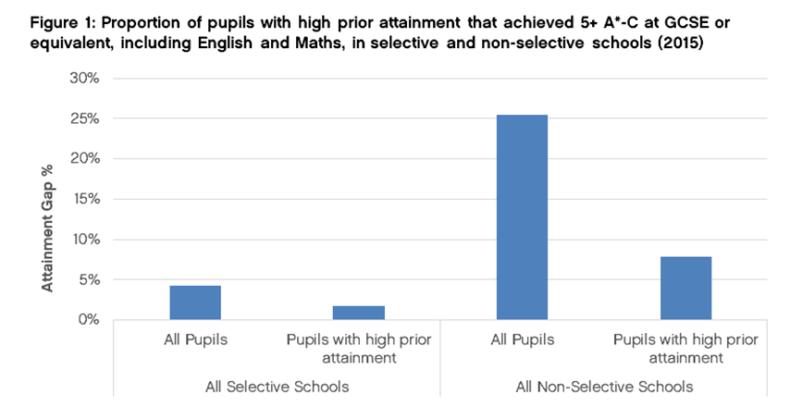

Redressing this is especially important given how strong the evidence is that grammars offer huge benefits to academically bright, disadvantaged children. Data from the Education Policy Institute shows that the attainment gap between those who receive Free School Meals and those who do not is just 4.3 per cent at grammar schools, compared to 25.5 per cent at non-selective schools. Among pupils with “high prior attainment”, the gap is just 1.7 per cent as opposed to 7.9 per cent.

So the key to success for the Government’s planned new grammar schools is how they advance the interests of such disadvantaged pupils – and help reduce selection by house price.

On that front, there are two key areas that ministers will need to focus on in their upcoming White Paper on education.

The first is that there are currently many areas of the country that have few “good” or “outstanding” schools. The most egregious example is the borough of Knowsley in Merseyside, which last year closed down its only sixth form college and reports 0 per cent of pupils attending good or outstanding schools. The Isle of Wight, Blackpool, Bradford and Swindon all have more than 50 per cent of pupils attending schools deemed to be failing or in need of improvement.

Areas such as these would be ideal areas for new grammar schools, offering opportunities for academically bright children from disadvantaged backgrounds and helping to reduce selection by house price. The White Paper should therefore identify them as preferred locations for new grammar schools – whether that be via converting existing comprehensives or by creating new grammars via free schools. It is also vital that standards for all schools in these areas improve, which means learning lessons from the improvements observed in the selective London boroughs.

Of course, this will not be enough on its own: other measures to increase access for the disadvantaged will be needed. For example, where existing schools are seeking to convert to grammars, they will need to pursue active programmes to encourage disadvantaged pupils, that will ensure the intake is representative of the community. That includes things like familiarising children from disadvantaged backgrounds with the format of the tests, to guard against “teaching to the test”.

Pushing through legislation to introduce new grammar schools will no doubt be tough. A sizeable segment of the educational establishment is opposed to Theresa May’s proposals, and even some members of her own party seem intent on derailing the programme.

But these are reforms that are worth pursuing. If the new wave of grammar schools are targeted in appropriate areas, and more disadvantaged pupils are encouraged to attend, then it will not only drive up performance, but alongside the impressive record of the recently established free schools it might just help tackle the problem that Andrew Adonis identified so long ago.