“It was right in everyone’s face. Tyler and I just made it visible. It was on the tip of everyone’s tongue. Tyler and I just gave it a name.” Fight Club

There has been much talk in America this past year of whether the ‘libertarian moment’ has finally arrived – the political awakening of a movement that has always existed in (and perhaps even exemplified) America, but has been without obvious representation.

It is a question that has big-government progressives like Paul Krugman or the writers at Salon so fearful that they have taken to penning comforting columns about how libertarians can never really break through because of their limited numbers.

Meanwhile, critics opine on American conservatism’s great image problem – a possibly incurable hangover from the George W. Bush years – and the shifting demographics that mean the Republicans may find it increasingly hard to capture the White House in future elections.

These arguments have been used to insist the Democratic Party can move ever more towards a progressive-left agenda while maintaining the electoral support of the American people. Amidst this, National Review writer Charles W. Cooke’s new book ‘The Conservatarian Manifesto: libertarians, conservatives and the fight for the right’ (released March 10) offers a welcome framework for drawing these two uneasy bedfellows together in something more permanent than their on-off post-Barry Goldwater love affair.

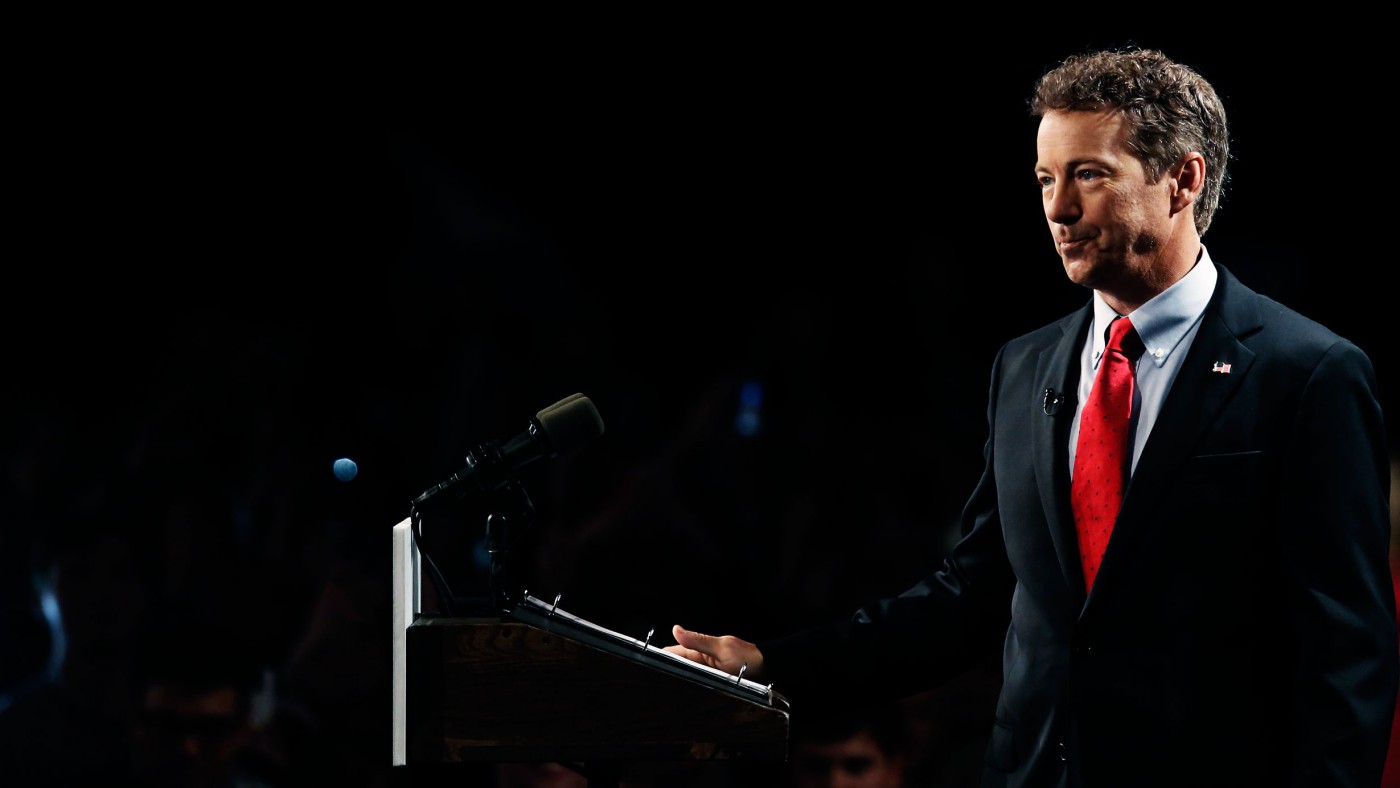

If this seems a Herculean task, it’s important to note Cooke is not ignorant to those areas where agreement is probably too great to bridge: particularly defence and immigration. This is evident in the current Presidential primary run of Kentucky Senator Rand Paul – son of libertarian standard-bearer Ron. His evolving foreign policy position is designed to tap into the failures of America’s muscular interventions while mitigating concerns about his father’s isolationist views. It’s a position that is too much for some libertarian purists to accept… there is an ever-increasing band of dilettantes crying out on the Facebook posts of Reason Magazine: “screw this guy – I’m voting Gary Johnson!”

Paul himself has sought distance from the libertarian tag; his buzzphrase “constitutional conservative” is designed to placate those who view the former as either hedonists or loons. This tag essentially means the same thing as ‘Conservatarian’ – a portmanteau Cooke has inherited from those he would meet who feel ‘conservative around libertarians, and libertarian around conservatives’.

President Reagan once described libertarianism as ‘the very heart and soul of conservatism’, and Cooke’s lynchpin for this relationship is federalism – the decentralisation of power back to the state and local level. This is not a radical move away from instinct as when Daniel Hannan and Douglas Carswell proposed something similar for the UK, but a return to American founding principles.

“The federal government operates at the sufferance of a charter of limited powers that were selectively granted to ensure that those few things that the states cannot do on their own can be achieved nationally. The states, by deliberate contrast, are where the real political power lies.”

It is federalism, Cooke suggests, that is the reason such disparate individuals as a Portland hipster and a Baptist bible-belter can coexist peacefully in the same nation.

This devolution of power is instrumental in satisfying the shared yearning for liberty that both sides possess. Libertarians and tea party conservatives alike remain dissatisfied with the performance of Republicans in office – not just the huge growth of the state under a big government (or ‘compassionate’) conservative like George W., but that even radical Republicans like Reagan could not truly cut the federal government, but just slow down the speed of growth. This is a very recent invention of American life – until FDR, the federal government was able to intervene only in commerce that was literally between the states.

The idea that states can confidently make their own choices on some of the most divisive questions – instead of federal impositions on gay marriage, marijuana, gun rights, etc. – both unifies conservatarians and allows them to retain their differences. To conservative Republican politicians, he offers some eminently sensible advice: that they might get used to saying “I don’t mind what you do” on issues that don’t affect them. The philosophy also embraces the generational divide that conservatives must bridge – even a majority of young Republicans are pro- gay marriage and marijuana legalisation (curiously though, young people are becoming more pro-life).

Cooke warns that focussing on individuals, such as Presidential candidates like Paul, can be counter-productive: the federal government remains hugely unpopular no matter who manages to gain office – people prefer their local and state legislatures (and in that order). He also correctly identifies that truly radical republicans are not the electoral ugly sisters that many people assume they are – the class of ’94 that swept the House and the more recent Tea Party-driven seizure of Congress demonstrate that the death of the right is not inevitable.

For a Brit, the book is worth reading for its chapter on gun rights alone – a subject Cooke is particularly knowledgeable on having written his Oxford undergraduate dissertation on the passage of America’s second amendment, much to the horror of many of his contemporaries. If you want to challenge your smug assumptions that America should simply ‘ban guns’, start here.

There is no doubt the book is at its strongest when demonstrating just how detached the progressive left has become from the American mainstream, and setting it apart from the conservative and libertarian positions. Indeed, it is a cute feature that the real-world copy of the book comes with a bright red sleeve, reminiscent of another infamous manifesto. On the demographic challenges the Republicans face, Cooke rightly identifies that Bush-levels of support among Hispanics would still not have delivered Romney victory, and that no group is one homogenous automaton but contains a plurality of views. Still, there is a sense that his advice of ‘carry on – keep on coming at them’ and win over larger chunks of all voters may not be enough.

For sure, the contract of marriage between the two sides will need to have more meat on the bones in the future. This is not a playbook – an aspiring candidate will not find 100 policies for a conservatarian government here. But Cooke’s treatise is a wonderful first step in lighting the fire for a movement – one that might both save the Republicans and finally deliver libertarians electoral success.

The Conservatarian Manuifesto. Charles Cooke, Crown Forum. RRP £20.