So far it is shaping up to be a big year for Oscar-nominated ‘true life’ stories in the cinema. This weekend following hard behind The Big Short comes Spotlight, a film about two great American institutions – the big city newspaper and the Catholic church. Spotlight is the name of the investigative desk at The Boston Globe, and the story is the almost incredible one of the highly organized involvement of the church hierarchy in concealing, even facilitating, the sexual abuse of hundreds of children over many years, and the work of the Globe’s team in uncovering the story. Almost incredible, except that it is now known to be true.

So is Spotlight’s true life story true to life? No, but it is close. Does it deserve its six Oscar nominations? Yes. Without the assistance of special effects or bizarre settings or even very much money (Spotlight’s budget is reported to be only $20 million, a mere nothing in today’s world of $300m films) it is good looking, expertly acted and utterly involving. Taking place almost entirely in the untidiest corners of newspaper offices or in nondescript streets and gloomy bars, Spotlight locks down your attention within two or three minutes of screentime and only once or twice does the grip loosen. There are no fights. No guns are fired. There is no romance, and little scenery. It is fascinating and appalling.

The background is this. In 2001 the Archbishop of Boston, Cardinal Bernard Law, filed a routine legal submission as part of the church’s official response to allegations against one of its priests. Journalists at the Globe noticed something in the submission that suggested a deeper story. Could it be that this was not the first time that Father John Geoghan had been accused? Could it be that he was a serial abuser, and that the Cardinal had known it, and covered it up? And could that be a pattern?

It is an archetypal story about the ability of an established tradition and hierarchy to sustain itself in the face of evidence of its rottenness. The story was so big that it was effectively invisible – until it was broken, and within a couple of years over 150 priests were accused of sexual abuse and Cardinal Law had resigned. It is a story that can now be seen as something that extends far beyond its setting – it is one part of the great counter-establishment insurgency of the last two decades. The Boston Globe had a leading role in the drama, although the earlier failure of journalists at the Globe to follow up on evidence they already held is part of the story, and one of the springs of the drama: from an early point we know someone at the Globe had failed to act (the final reveal on that storyline is a surprise). But all institutions, including the Fourth Estate, are subject to status quo blindness.

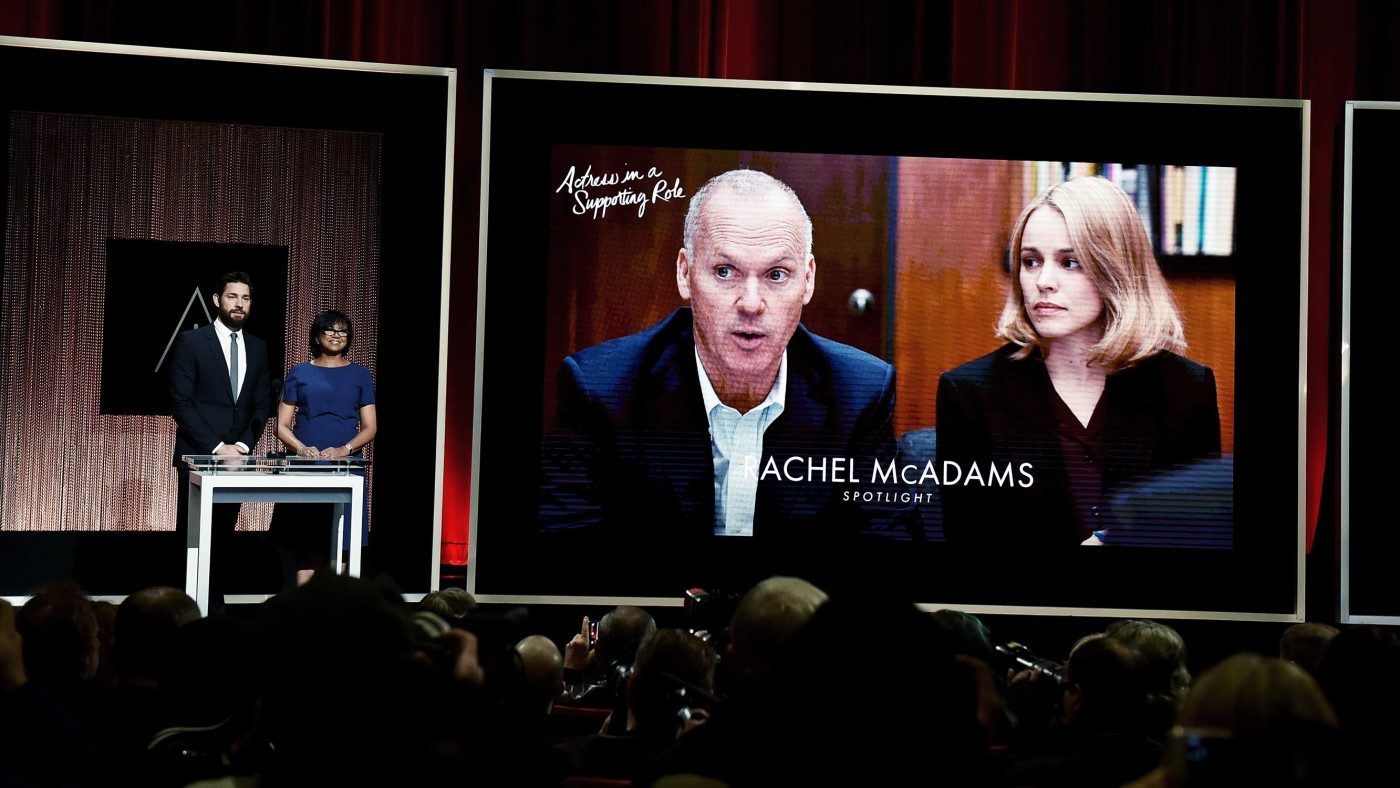

There is hardly a weak performance in the ensemble. Michael Keaton is outstanding as the leader of the trio of journalists that lead the investigation, but the supporting playing is what makes a film almost entirely composed of talking-head scenes and exposition of complex legalese so compelling. It does falter once or twice, but momentarily. The horrible nature of its subject, and the fact that no one ever wants to talk about child abuse – least of all its victims – is ever present.

One of the big stars of this film is not credited, and the name of the star is the city of Boston. It is a city built for cinema, and there is a long list of distinguished films that have made use of the foreboding Boston colours which seem to invite stories of crime and conspiracy. The pewter light from the Atlantic and Charles River has washed through films like Scorsese’s police conspiracy masterpiece The Departed, or the grimy Robert Mitchum thriller The Friends of Eddie Coyle. But the Boston film that casts its shadow all through Spotlight is Clint Eastwood’s Mystic River. Like Mystic River, Spotlight revels in the monumentally dreary Boston streetscape, where it is perpetually raining or snowing, and where the only refuge seems to be the warmth and flourescent light of The Boston Globe offices. Spotlight lacks the emotional punch of Mystic River, but makes up for it in subtlety and ambition to tell a complex story in all its detail.

Of course the world of newspaper journalism has been slightly tarted up to Hollywood standards when it comes to looks and wardrobe, but only slightly. Journalism may still have its glamour, but Michael Keaton, John Slattery and Rachel McAdams all look just a little bit too healthy. The alcoholic lunchtimes and epically charged ashtrays may have gone, but the ancient marks of the trade remain: most real life journalists still look tired and sorrowful and in desperate need of a holiday. Perhaps even more so today, when the workload has increased and the rewards diminished.

There is some irony in the fact that a successful Hollywood – and this is a golden age of mainstream acting and film-making – should be celebrating the world of the big newspaper, just as the world of the big newspaper is threatened with ruin. The Boston Globe is not an exception. The newspaper came close to collapse in 2009, and the question of whether it can make a go of it with its model of paid online distribution is unanswered.

Would The Boston Globe have the funds and the confidence to unravel the Spotlight story today? It wouldn’t cost much in Hollywood terms, but still way more than many large newspapers can spend on a single story. Spotlight is a drama of current affairs, but it threatens to be history.