When Theresa May became Prime Minister, one of her first promises was (as the Daily Mail put it) to protect our “City icons” from “foreign vultures”.

It’s a widely shared complaint. Too much of Britain is in foreign hands. From our rail companies to our energy companies, from London property to Cadbury’s chocolate, we’ve let asset-stripping foreigners make off with the family silver. And with the plunge in the pound due to Brexit, the problem is only going to get worse.

But there’s another argument to make. Which is that the single simplest way to make this country more prosperous, to restore its economic dynamism, would be to gift-wrap those City icons and flog the lot.

That is the implication of a devastating new blog by two Bank of England economists. It points out that, controlling for everything else, foreign ownership makes each firm 50 per cent more productive. That is partly because they are more likely to collaborate with others, and more likely to be run by meritocratic managers than scions of the founding family. But it is also because they invest far more in R&D – five times as much, on average.

In fact, while such firms employ only 15 per cent of the UK workforce, they account for 50 per cent of R&D spending – and 30 per cent of total productivity growth.

Productivity isn’t everything. But as Paul Krugman says, in the long run, it’s almost everything. Higher productivity is what drives improvements in wages, living standards and prosperity in general. Andrew Haldane, also of the Bank of England, pointed out in a speech on the issue back in March that if productivity had remained flat since 1850, we would be only twice as rich as the Victorians. As it is, we are 20 times better off – because each of us contributes vastly more to the economy for every hour of labour.

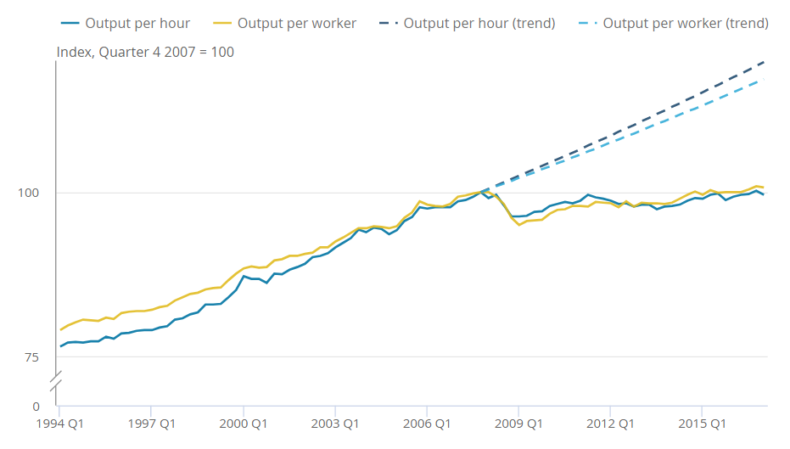

And this is the single biggest problem with Britain’s economy. Since the financial crisis, the UK has created jobs at an enviable rate. But the flipside is that productivity has flatlined. Between 1950 and 2008, it grew at an average of 1.7 per cent a year. Since then, it has fallen by 0.36 per cent a year. The latest figures, released this week, only confirm the trend.

These are statistics that should set not alarm bells ringing, but whacking great air raid klaxons. Because the global economy is polarising, as Haldane points out, between the productive and the unproductive – between “frontier” firms and countries, which make full use of the latest technological and managerial innovations, and laggards. As Britain slips towards the back of the productivity pack, it becomes a place that relies not on the dynamism of its workers, but the fact they are dirt cheap – which is not a comfortable or sustainable position to be in.

So how do we fix this – apart from inviting in those foreign “vultures” to teach us how to be proper capitalists?

One solution suggested by Sir Charlie Mayfield’s official Productivity Review is to make firms aware of the problem. This sounds ridiculously simplistic – but the hypothesis is that, just as each of us thinks we are a good driver, every firm tends to think of itself as well run. Confront them with the truth, and they will sharpen up their act.

We also need to expose firms to the global markets. Those who export tend to be more productive than those who don’t. As I’ve pointed out before, some Brexiteers saw a Leave vote as a form of shock therapy, a way of forcing poorly run British firms to shape up their act.

But this is a policy challenge that stretches beyond company management. We need better education and training. We need greater investment in IT. And above all, we need workers to be in the right places.

One of the most interesting laws of population is that productivity, like most other things, scales up along with community size. Huddersfield will never be as productive as London not because of any deficiency in its inhabitants, but because it is smaller.

So one of the reasons the planning system has inflicted such devastating economic harm on Britain is because low housebuilding and high house prices are the perfect recipe for pushing workers out of the most productive parts of the country, for trapping people in towns and jobs where they cannot fulfil their economic potential.

Sure enough, a new Resolution Foundation study confirms that the young are decreasingly likely to move for work – in other words, that the British economy is getting worse, not better, at marrying people to the most productive jobs, and giving them the highest possible salaries.

Britain was once known as the sick man of Europe. Today, we are still sick. And low productivity is our seemingly incurable disease.

This article is taken from CapX’s Weekly Briefing, which you can sign up to here