“Let China sleep,” Napoleon Bonaparte pronounced, “for when she wakes she will shake the world.” For the past 30 years or so, this apocryphal sentiment formed the basis of conventional wisdom in the West. Yet it is now apparent it was not China that was sleeping, but the West.

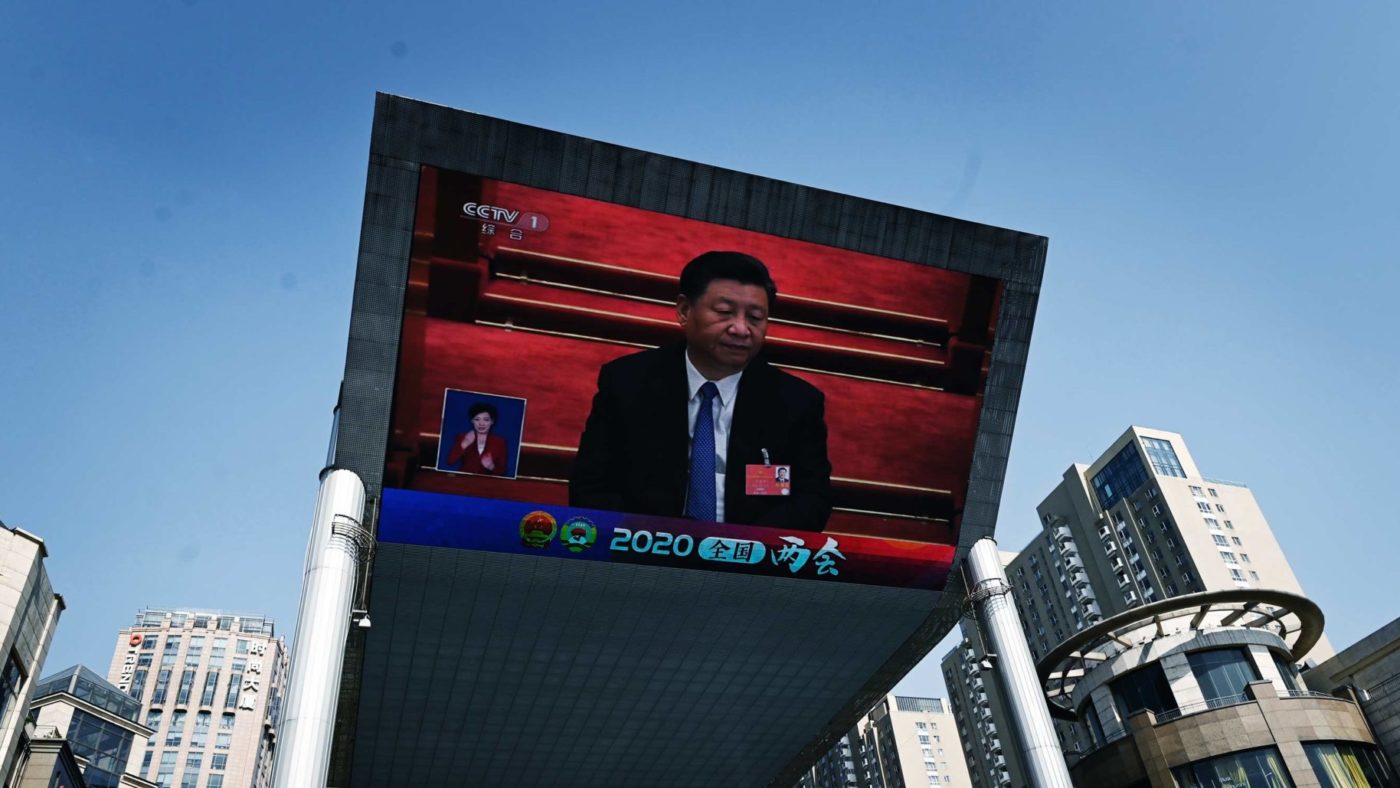

Since being elected head of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in 2013, Xi Jinping has put his country on a path of confrontation with the outside world. Today, even as the Chinese capital records more new Covid-19 cases than it admitted to at the first peak of the outbreak, Xi’s aggression is spreading and intensifying.

Hong Kong has come under the grip of Chinese ‘law’. Taiwan faces military threats and crude political subversion and increased military action on the Indian border seems designed to warn Delhi off building stronger ties with the US. Renewed incursions in the South and East China Seas undermine regional security, creating a flashpoint for armed conflict with the US. Canada faces hostage diplomacy, Australia is threatened and bombarded with cyber-attacks and Britain is told to allow Huawei into its 5G network or face unpleasant consequences.

Inside China’s borders, the authorities brutalise not only ethnic minorities but also religious groups and dissidents from the majority Han population. Repression is taking place on a scale not seen since Mao’s dictatorship.

This is not the image of a benign global partner which successive CCP leaders spent decades building up and selling to the West. As recently as 2017, Xi marketed this brand in his Davos speech, extolling “open and win-win cooperation”, a “shared future for mankind” and the importance of “not pursuing national interests at the expense of others”. Nothing could be further from the zero-sum policies being driven forward today.

What has changed, and why?

At Davos, Xi noted how China’s policies emerged from the ‘wisdom of its civilisation’. This was code for a superior mode of collective governance linked to the teaching of Confucius. As Beijing embraced a form of ‘capitalism with Chinese characteristics’ in the 1970s, lifting the country out of the dramatic poverty of the Mao era, this link to ancient humanist traditions encouraged Western hopes that a wealthier China would eventually adopt liberal values.

But this was no more than a façade. From its emergence 2000 years ago, the Chinese state has rarely followed Confucian principles in anything but name. For Confucius, legitimate rule hinged on the exercise of virtue and moral authority, which would render a leader worthy of receiving the ‘Mandate of Heaven’. But he searched in vain for any individual sufficiently virtuous to rule without laws and force.

Judged by Confucian standards, the CCP dictatorship represents everything that is most illegitimate and undeserving of the ‘Mandate of Heaven’. In fact it owes more to Legalism, a political school that rebuffed ‘soft’ Confucian morality in favour of authoritarian rule by laws. Since the reign of China’s First Emperor, Legalism has provided the real foundation for state authority.

But current CCP conflict with the rules-based international system derives not from China’s Imperial past but rather Communist ideology. The CCP is a revolutionary movement whose power came, as Mao wrote, “out of the barrel of a gun”. Xi’s power stems from his role as both supreme CCP and military leader. The CCP leadership may look like a bland oligarchy of pseudo-capitalists, but are in fact classic Marxist–Leninists carrying forward a ‘permanent revolution’ of struggle against forces they see as inimical. These, of course, include all the fundamental values of democracy, freedom, and human rights which underpin the rules-based system.

For years after Mao’s demise, his successor Deng Xiaoping removed constraints that had prevented the Chinese people from becoming wealthier, and even tinkered with low-level political reform. But all this ended with the Tiananmen tragedy of 1989, after which Deng and his fellow Long March veteran henchmen dispensed with any thought of political liberalisation.

The CCP recognises only two types of states; rivals to be defeated and clients to be exploited. Tellingly, the PRC has only one avowed ‘ally’ – the so-called Democratic People’s Republic of Korea. Xi has weaponised the wealth which Deng allowed to grow, using it to spread Chinese sharp, hard and soft power across the world.

All of this was making headway until Covid-19 emerged in Wuhan, and the sclerotic, top-heavy CCP regime utterly failed to stop its global spread. To ensure survival, the CCP knows no other course but to throw its forces into existential struggle for world domination, exploiting Western distraction and coercing less liberal states to slide deeper into Chinese dependency. Only through rigorous honesty as to the true nature of the Chinese regime will the West be able to resist Beijing’s designs. To succeed, we must stand united.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.