The great paradox of the Trump ascendency was that the man who rode the wave of anti-elite sentiment all the way to the White House was a multi-millionaire Manhattan property developer.

For Richard Reeves, this apparent contradiction isn’t such a surprise. In his new book Dream Hoarders, about social mobility in America, he argues that “Trump’s supporters have no problem with the rich. In fact, they admire them. The enemy is upper middle-class professionals: journalists, scholars, technocrats, managers, bureaucrats, the people with letters after their names. You and me.” And probably you, too.

But the reason Reeves’s book is making waves is that he goes further – to argue that the Trumpites have focused their ire on exactly the right target. “There is one good reason why many Americans may feel as if the upper middle class is leaving everyone else behind,” he writes. “They are.”

The one per cent might make for convenient economic villains. But according to Reeves, the real dividing line is between the top 20 per cent and the rest.

Between 1979 and 2013, the top fifth of US households – which Reeves settles on as a working definition of the upper middle class – saw a $4 trillion increase in pre-tax income. The rise for the bottom 80 per cent, by comparison, was just over $3 trillion. For every extra dollar earned by the top one per cent, two extra dollars were earned by the next 19 per cent.

Of course, lumping the top one per cent in with the next 19 seems a bit of a stretch. The runaway winners in recent economic history are – without doubt – those at the very top.

But it isn’t inequality that Reeves is worried about – or at least, not inequality of income. Rather, it is inequality of opportunity.

However you slice it, social mobility in the US is not what it could be.

Whatever dataset they use – income, wealth, education – the experts arrive at the same conclusion: there is a “stickiness” at the very top and bottom of American society. Those born to parents in that top 20 per cent of American society have a huge head start over the rest when it comes to securing a spot for themselves. And most of those at the bottom find it almost impossible to break out.

If Reeves’s name is ringing a bell, it should. A former head of Demos, he was brought into Downing Street by Nick Clegg. He moved to Washington, where he now works as a Fellow at the Brookings Institution, in part to escape what he always thought was a society preoccupied by class. “I always hated the snobbery and class distinctions of the UK,” he writes. “But the harder I have looked at my new homeland, the more convinced I have become that the American class system is hardening, especially at the top. It has, if anything, become more rigid than in the United Kingdom. The main difference now is that Americans refuse to admit it.”

The problem is so alarming because equality of opportunity is the cornerstone of the very idea of America. It squares the circle between the country’s commitment to individualism – “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness” – and egalitarianism – “all men are created equal”. It is, however you define it, the essence of the American dream. And without it, everything starts to unravel.

A society which doesn’t reward merit, and in which people are in jobs because of who their parents are rather than what they are capable of, is not one that is as productive and dynamic as it could be. And the blame, Reeves argues, falls squarely on the beneficiaries of the unfair system: the “dream hoarders” of the book’s title.

Though many of them would profess to support the liberal ideal of equality of opportunity, they don’t practice what they preach. Some have tricked themselves into thinking their background has nothing to do with their success. To borrow American football coach Barry Switzer’s baseball metaphor, they were “born on third base and go through life thinking they hit a triple”.

But overwhelmingly the problem is a kind of social NIMBYism – typified by a colleague of Reeves’s who urges him to delay publication of the book until after his child had finished their internship at the think tank. You hope – but cannot be sure – that he is joking.

The upper middle class, like everyone else, will do absolutely everything they can to help their children succeed. But the growing gap with blue-collar America when it comes to things like family breakdown means those children’s advantages over the rest are more than just economic.

The top 20 per cent are hoarding dreams in two ways. There are their actions as parents – the tutors, the piano lessons, the internships and the legacy system that gives their children preferential treatment in college applications.

And then there are the political decisions they make. From presidential elections down to school zoning decisions, their first instinct is to further entrench the advantages they have. Reeves quotes Paul Waldman, who thinks that the upper middle class is the single most dangerous constituency for a politician to anger. They are “wealthy enough to have influence, and numerous enough to be a significant voting bloc”. They are also the group from which the columnists, think tank staff members, policy advisers and – overwhelmingly and increasingly – the politicians themselves are drawn.

Much of what Reeves proposes is hard to disagree with. To take a particularly low-hanging fruit, colleges’ preferential treatment to so-called “legacies” – applicants who are the children of alumni – is nothing more than “affirmative action for the rich”. Ditching it is harder than it sounds. But doing so, Reeves argues, would be a meaningful restatement of America’s commitment to meritocracy.

Similarly, tax breaks designed to broaden access to higher education have become a means by which the upper middle class preserve economic status. It is hard to disagree with Reeves when he says they should go.

But Reeves places a lot of hope in policies that amount to little more than tinkering. Visits to the homes of families with a newborn baby sound sensible, but would they really level the parenting playing field?

Reading Dream Hoarders – or Tyler Cowen’s The Complacent Class, which sees America slipping into social stagnation – leaves one with a sinking feeling that little will change. (And I have a sneaking suspicion Reeves feels it too.)

These issues are so politically fraught because social mobility is, by definition, a zero sum game. There is only room for 20 per cent of the population in the top 20 per cent. And so upward mobility necessarily means downward mobility – less of a vote-winner.

Like the hiker who knows the dangers of getting between a bear and her cub, politicians are aware of the political risks that come with being seen to get in the way of parents doing their upmost to help their children.

One of the most interesting questions raised by the book, and only dealt with briefly by Reeves, is whether the problem is getting worse. He is right to say that the anecdotal evidence would suggest that the upper middle class is piling advantage on top of advantage in a way everyone else will struggle to keep up with. But, as Reeves acknowledges, the data isn’t clear. Raj Chetty, a leading economist studying social mobility has found that “[relative] social mobility has remained stable over the second half of the 20th century in the United States.”

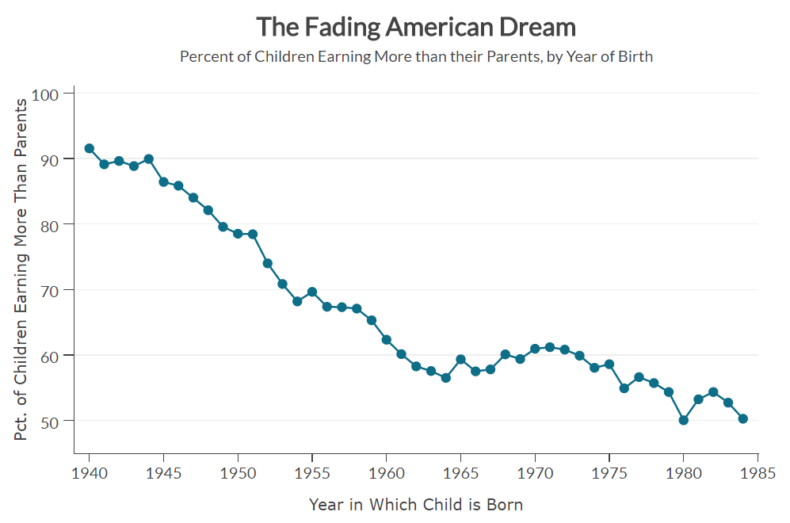

Relative social mobility – the extent to which we inherit our parents’ position in society – may never have been in great shape. By another measure, however, the American dream is on the ropes. One definition of that idea is of growing prosperity for all and, on an individual level, for someone to out earn their parents. The percentage of Americans earning more than their parents are plummeting.

Source: Raj Chetty, The Equality of Opportunity Project

The question, then, becomes one of priorities. Both relative and absolute mobility are worthwhile ways of measuring society. And they are closely related. But what should be the political focus? Despite Reeves’s best efforts – and Dream Hoarders is a fascinating guide to an important subject – I would say the latter. Not least because it avoids the divisive dead-end that is zero-sum politics: better to worry about increasing the size of the pie than squabble over how the pie is sliced up.