In the hurly-burly of an election campaign, the long view tends to suffer. That is doubly the case when one of the main parties has based their offer to the British people on the idea that the country has become irredeemably awful.

Nowhere is this more the case than with the NHS, on which Labour has concentrated so heavily. One of the many baleful things about this campaign has been that so much time and attention has been spent on the fantasy of “selling off” the health service, and very little on how a future government might sensibly address the challenges it faces.

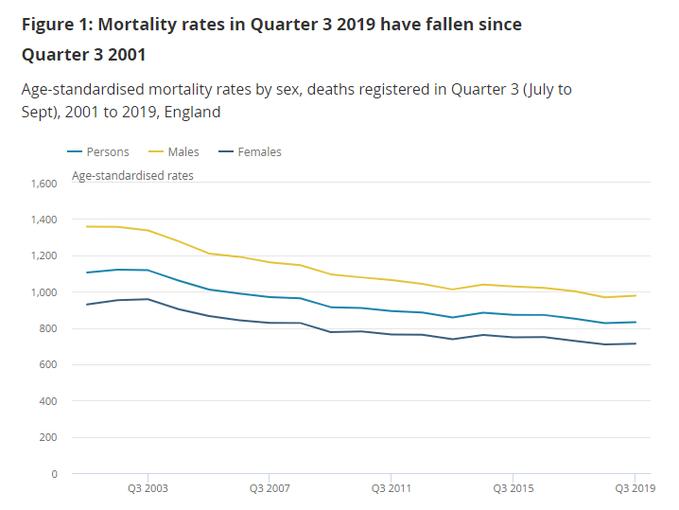

A new release today from the Office for National Statistics makes for both cheerful and sobering reading on this point. Cheerful, because – as my colleague Robert Colvile noted this morning – it shows that mortality rates in the UK have fallen 25% since the turn of the millennium (when the statistical series began).

If you live in Britain, you’re more likely to live a long life now than at any point in our history, and that’s surely something to celebrate. But it does also have serious consequences. One of the reasons there are such pressures on the NHS is that the overall make-up of the British population has got a lot older. That is in many ways a wonderful thing, but it does also mean that more patients are presenting with age-related health conditions and multiple, complex needs.

It’s hard to overstate the scale of that change. One estimate suggests that from 2012 to 2032 the populations of 65-84 year olds will go up by 39% and the number of over-85s will more than double. There isn’t space here to go into the myriad implcations that will have for the structure of the British economy, but it’s obvious what it will mean for health and social care – we will have to come up with a way to manage what is certain to be hugely increased demand in the future.

A political and media debate that seems to revolve almost entirely about funding misses this crucial dimension. Screeching about ‘privatisation’, or raising the spectre of a disastrous US-style private health system, does little to advance things.

Hospital treatment is, of course, only one part of this. Just as important, both fiscally and in terms of quality of life, is sorting out our social care system. One of the great tragedies of recent political life is that the 2017 ‘dementia tax’ debacle has re-toxified an issue that ought to be of front rank importance for all political parties.

The Conservatives offer a cross-party solution of some sort, without much in the way of specific, while Labour pledge to spend £6bn more by 2020/21 on personal care – not an outrageous suggestion in itself, but one tucked into a manifesto so replete with extravagant spending commitments it’s pretty hard to take any of it seriously. As another of my CPS colleagues Tom Clougherty points out today, Labour’s plans are very far from ‘fully costed’, and their proposals to hike corporate taxes would be a “disaster for businesses, workers and savers”. With such an extensive wish-list, Labour would soon have to either turn on the printing presses (not a possibility we would exclude) or raise VAT, national insurance and income tax on the many, not the few – blowing apart their claims that only those at the top would have to pay more.

Whoever does triumph in tomorrow’s election, though, an inflection point is soon approaching where politicians will need to come clean with voters. Simply put, if we want a society where old people are taken care of, it will mean either paying higher taxes or radically shifting spending priorities from other areas.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.