On Sunday morning, Johnny Rotten will collect his bus pass.

I’m exaggerating, of course. For one thing, he’s got to wait till Monday for the offices to open, assuming he’s got the right forms. For another, he’s just 60, so he’ll only be able to claim free travel in London: to get around the rest of the country, he’d have to wait another five years. And he apparently spends most of his time in Los Angeles anyway.

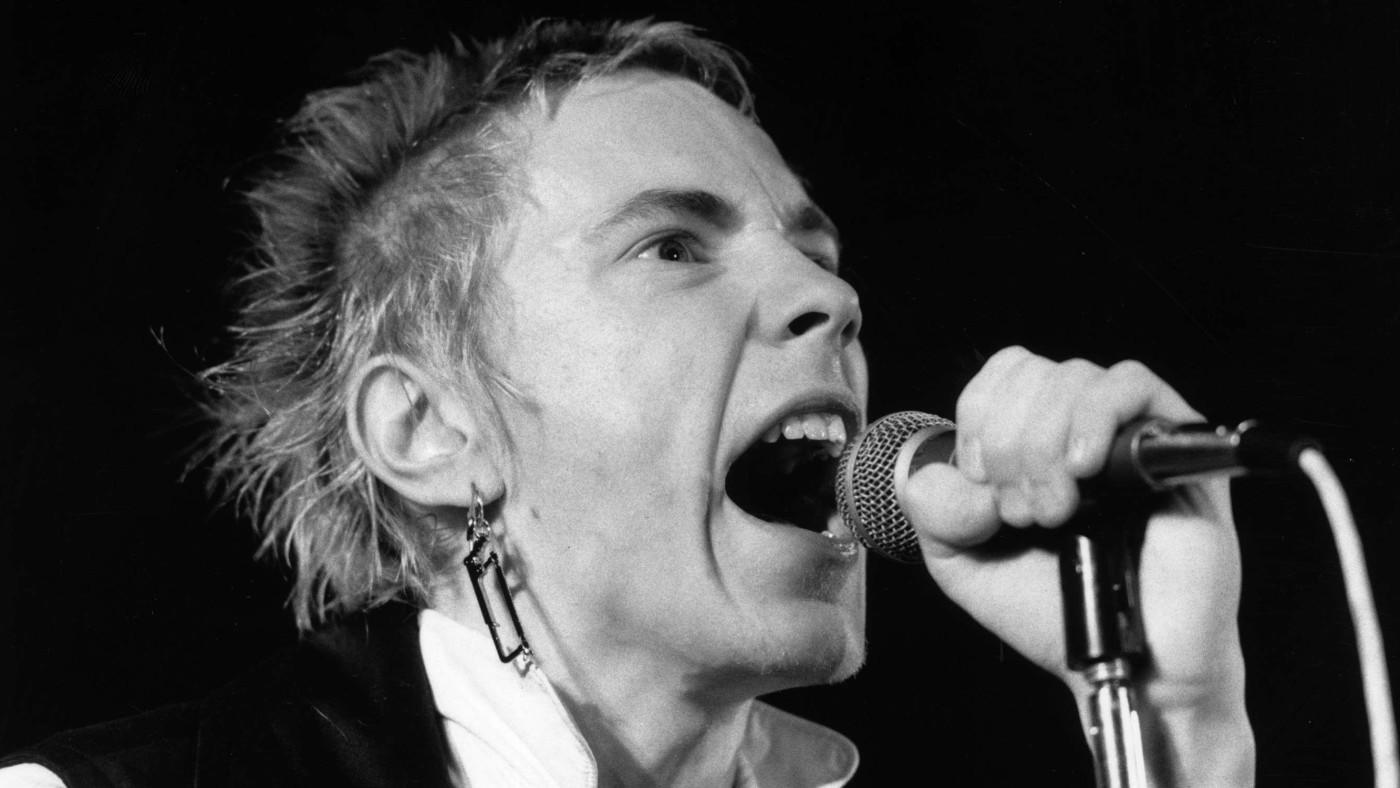

But still: John Lydon. Johnny Rotten. The snarling, simmering symbol of punk rebellion, is 60. It’s enough to make you wonder where all the years went – before getting distracted by the letter from the doctor reminding you to take your statins and turn up for your scheduled prostate inspection.

There’s a weird paradox here. Popular culture, and life in general, seems to be moving faster than ever (in fact, I’ve just written a book about that very phenomenon). But in music at least, we’re still operating under the terms of trade set out by Elvis, the Beatles and others more than 50 years ago.

For example, it’s standard, in pieces like this, to note that the rock stars who sang “Hope I die before I get old” and similar anti-establishment anthems are now multi-millionaires of pensionable age. It’s less often pointed out (because I only just worked it out) that the song that line comes from – “My Generation” – was released closer to the First World War than to today. Yet it’s remained part of the pop cultural corpus in a way that previous genres – jazz, big band, ragtime, music-hall – simply haven’t. How come?

I think there are two explanations for this: technology, and demography. Technology has made it ever easier to preserve, reproduce and share different forms of music: with instant access to the past (presently via streaming services such as Spotify) it’s easier to appreciate its virtues. But the effect of demography is more interesting.

Modern pop, and rock, were the music of the Baby Boomers, that monstrous regiment who, by virtue of sheer numbers, seized the commanding heights of popular culture and have yet to let them go. And one of the things that made them different from previous generations – as I’m very much not the first to observe – was their continued obsession with youth.

Just as they never shed jeans and T-shirts for cords and pipes, so they proved willing to listen to, appreciate and appropriate, new music. That, in turn, meant that it was harder to sweep the old stuff away: it’s impossible to react against something when it’s a vast, agglomerative melange. (It’s also possible, as some people will argue, that the three- or four-minute pop song reached such a height of perfection in the Sixties and Seventies that, as with Shakespeare’s plays, everyone since is just colouring around those lines.)

Which brings me back to John Lydon. When he pops his clogs (hopefully in the dim and distant future), he’s sure to be accorded the same kind of reverential retrospectives accorded recently to David Bowie, if possibly turned down a notch. But will the same apply to today’s musicians? Will the schedules be cleared in a few decades’ time to mark the death of Drake, or Ed Sheeran, or Harry Styles?

It’s possible to make a case for some artists who may well ascend to that status – Beyonce, say, or Adele. But they’re less common than you think. Indeed, it’s now accepted within the music industry that the number of copper-bottomed superstars – not just successful acts, but world-dominating, Glastonbury-headlining, Super Bowl-playing superstars – is more limited than ever before. There is, thanks to a new baby boom, a bigger market for music than ever before. But there seem to be fewer and fewer musicians who truly matter.

And this is the fascinating thing. Our culture is so fragmented that it’s hard for anything to assume the kind of monolithic importance that pop music used to – to whip up the same amount of strong feeling, whether for or against. And the space that new stars might occupy has, in part, been taken up by the acts that came before: if you want an anthem expressing a particular emotion, there’s probably one already to hand.

At the same time (and this is something I get into in my book), pop music’s role within the culture has changed. There are still big hits, but they don’t come with the same agenda. A Bowie or a Rotten seemed to be making a statement about what music should and could be. Their successors mostly just want to make you dance. If that makes modern pop seem pretty vacant – well, I’m sure someone wrote a song about that.