A great deal has been written over the past week on the Government’s plan to reform the English planning system. Inevitably, much of the early commentary has focused on the vision rather than the substance of the proposals.

In some parts of the consultation, both the substance and the vision are to be welcomed. For example, the consultation highlights the fact that currently only 50% of local authorities have an up to date local plan, which even then take on average seven years to implement. Hence, anything that can be done to broaden and quicken this process should be welcomed, as should the move towards a digitised and more accessible system.

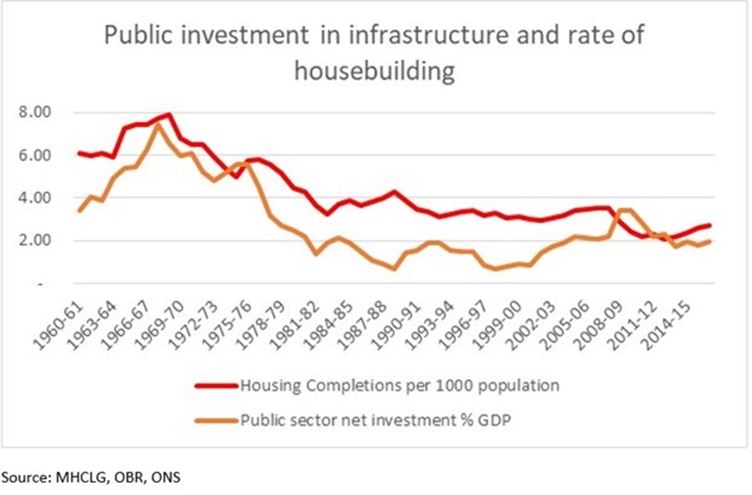

One area of the consultation worthy of more attention is the focus on infrastructure. The reason for this is simple. Infrastructure is an essential component in growing housing output. As the chart below shows there is a strong relationship between housing output per thousand of the population and investment in infrastructure.

To achieve growth in infrastructure investment will require strategic planning to be taken more seriously. The consultation recognises this, commenting that new developments brings with them a increased demand for public services and infrastructure, from GP surgeries to schools and transport links. Hence an infrastructure plan must be in place to enable sufficient development, while ensuring that local communities do not see a degradation in the quality or availability of their local services. However, infrastructure planning right now is often far too reactive and far too localised.

On a positive note the Government has decided to bin the failed duty to co-operate between authorities and suggested that very large projects might instead be designated as part of the Nationally Significant Infrastructure Projects regime. While this might work for Crossrail II or the Oxford to Cambridge corridor, it is less clear this makes sense for medium-sized projects.

Combined Authorities, such as the West of England, provide an ideal existing base upon which to build this model, given they control both economic and transport planning and work closely with the local authorities when it comes to housing plans. However, for the vast majority of local authorities, the idea of integrating housing and infrastructure is largely ignored. This needs to change.

Currently, the vast bulk of public infrastructure investment continues to flow from central government. Recent moves to change this such as the Community Infrastructure Levy (CIL) have had limited impact, raising no more than 4% of the funding for Crossrail. The Peace Review also noted that authorities were receiving as little as 50% of what they were expecting to collect. Section 106 obligations can also pay for very localised pieces of infrastructure, although the majority of these obligations tend to be related to affordable housing.

The Government evidently does not think these systems of funding work, which is why it has proposed to abolish CIL and S106 in favour of a new National Infrastructure Levy. As Housing Today explain it, rather than the current system which sees the CIL set locally and S106 contributions ‘subject to detailed negotiation’, the rate of the new National Infrastructure Levy will be ‘set nationally as a proportion of the sale value of a development, after a minimum threshold’. The Government hope this new set-up will raise more cash and deliver at least as much affordable housing as at present by capturing a greater share of the increase in land value that comes with development.

This shift in thinking is welcome. My research indicates that the current system only captures 42% of the increase in value after tax, leaving £10.7bn more per annum that could be used to support incremental investment.

The question though is whether the new Infrastructure Levy will really be able to provide the funds to boost infrastructure and housing output. The new charge will be levied at the point of occupation rather than at the planning permission stage on all new dwellings, including those currently exempt from CIL and S106. Given that local authorities would no longer have access to the CIL revenue upfront, the consultation supports local authorities borrowing against future CIL revenue.

However, as with all tax policy there is often a gaping chasm between theory and practice, and the history of it is littered with failures. A recent paper for the Scottish Land Commission highlighted that the “various attempts at capturing at least some of the uplift in land values through taxation…have proved to be contentious and, for the most part, have not lasted”.

Moreover, attempting to collect tax after development makes it harder to extract the full value due to potential behavioural changes. For example, the existence of a threshold may result in amendments to some projects so that they come under the threshold and therefore avoid having to pay the tax. Furthermore, it is unclear how the threshold will be set, particularly in areas where the uplift is limited, further affecting viability. And there is no analysis of how landowners might respond. The reality is that most new tax systems result in unintended consequences.

There is, however, a tried and tested alternative though. Instead of taking a huge risk and building a new, costly tax system that may or may not increase revenue streams, the Government can simply replicate the approach used in the past to build the garden cities and new towns. Simply amend the Land Compensation Act 1961, ditching the concept of ‘hope value’ – the predicted market value of land based on the expectation of getting planning permission for development on it – and thus enable the large-scale pooling of land by public and private bodies. Crucially, this approach would enable nearly all of the uplift in value to be captured to help pay for more infrastructure and affordable housing.

In the end, the decision as to whether landowners or local communities of entrepreneurs and workers (whose demand increases land values) should reap the rewards is a political one. Politicians can either decide to support an economic system that rewards hard work and innovation, or instead, as Churchill lamented, continue to reward landowners for contributing nothing. Simply creating a new tax does not fundamentally address the issue, and is unlikely to resolve the ongoing infrastructure deficit.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.