Yes, we get it. Marine Le Pen is a divider, a xenophobe, a dangerous nativist who’s willing to disregard individual rights of every kind to achieve her goal of Making France Great Again. She’s racist, homophobic and anti-Semitic. And you’ll delete us off social media if we even think about voting for her.

For many people, the paragraph above explains all you need to know about the rise and rise of Le Pen. She’s the perfect protest candidate, a Gallic equivalent to Donald Trump for the grumpy patrons of village bars in the South of France who want to stick two fingers up at the metropolitan elite.

But the idea that Le Pen is simply a protest candidate doesn’t hold water. The truth is that she is ahead in the polls not because she is so extreme, but because, for a whole lot of ordinary middle-class French people, what she says about protectionism sounds like common-sense economics.

On the website of the National Front you can find this press release, headlined “Vinci [a French construction company] chooses a Turkish subcontractor at the expense of French façade specialists: we need protectionism”.

“There aren’t 36 different solutions in order to respond to these attacks against employment linked to unfair international competition,” it says. “What is needed is targeted protectionism and economic patriotism to the benefit of French companies.”

In Le Pen’s 144-point plan for her presidency, she similarly calls for the defence of French jobs via “smart protectionism”. Whether the protectionism is “smart” or “targeted”, the idea has been in the vocabulary of the French far-Right for a few years already – but there’s still no explanation of what it entails.

Logically, it will involve leaving the Single Market and imposing import tariffs, but the question of how Le Pen adjusts to other countries’ responses, and how she deals with the inevitable rises in consumer prices, remains unsettled.

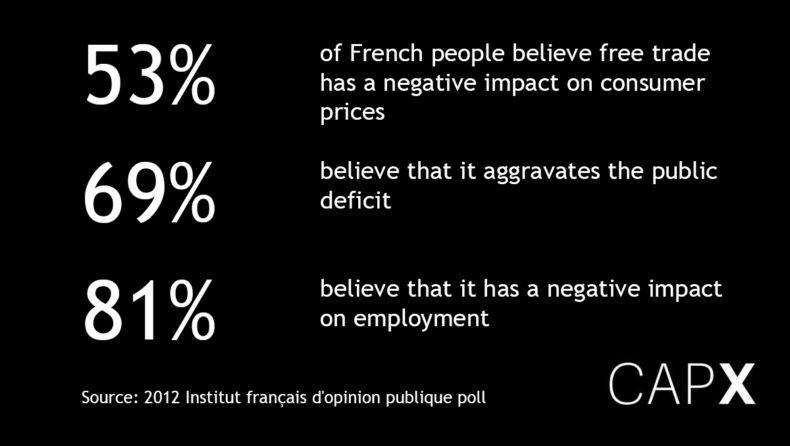

This lack of clarity (and sense) doesn’t seem to stop the French public liking the idea. According to an IFOP poll in 2012, prior to the last presidential election, 53 per cent of French people believe that free trade has a negative impact on consumer prices; 69 per cent assert that it aggravates the deficit; and a staggering 81 per cent believe it has a negative impact on employment.

These views are not limited to a particular demographic: they’re shared among private and public sector, between different kinds of professions, between urban and rural areas, working and retired, men and women. Nor did voting intention – whether a voter was far-Left, far-Right, centrist, conservative or socialist – seem to make much difference.

This helps explain why it has been so very rare for politicians here to come to the defence of the principles of free trade – and why Le Pen’s ideas are getting such a sympathetic hearing.

To his credit, Emmanuel Macron – the former economy minister now running as an independent outsider, and the favourite to beat Le Pen in the second round – has tried to bring some facts to bear.

In a debate last year with National Front deputy chairman Florian Philippot, he pointed out:

“We [France] even have more direct investments in China than the Chinese have in France. That’s the reality. So yes, let’s start a [trade] war with China with our short arms, it’s a very good idea that you’ve got there. They’ll kick out all the French companies in China as a reaction. We have a lot of French companies which sell components to Chinese producers…

“So sure, we’ll get into this war. You know what? We’re talking about 25 per cent of Airbus market share here. So you, Florian Philippot, will explain to the worker at Airbus that we’ll have to close down at least a quarter of the production sites in France because of your trade war with China.”

But where Macron uses facts, the far-Right uses the moral argument: it is standing up for France, and for French workers and companies, in the face of a hostile world.

Ultimately, the rise of the National Front is not about a culture war – it’s not primarily about the integration or assimilation of different nationalities and religions. It’s about the fact that France is riddled with the disease of unemployment. And just like a disease, it takes away people’s ability to focus, to consider a rational argument. It’s not terribly difficult to convince a dehydrated person to drink seawater if you have nothing else to offer them.

During this election campaign and beyond, free-marketeers need to fight the National Front’s regressive economics by providing real-life examples of what protectionism entails: fewer choices, higher prices, fewer jobs and toxic diplomatic relations. But they also need to make the case that ultimately, prosperity – and jobs – can only be created by free trade, and free markets.

Let’s just hope France’s leaders learn that lesson in time.