I can’t remember the last time I paid in cash. The rise of low-cost smartphone-enabled point of sales providers like SumUp, Square and iZettle have enabled even the smallest retailers to accept card payment. In London, the £5 minimum card payment is largely a distant memory. Some street food markets, which might have been the last place you’d expect to pay by card, have gone cashless.

It makes sense. The drawbacks to cash are unavoidable. It needs to be physically handled, taken to the bank, and kept secure. The latter issue can be a major challenge. My local coffee shop went card-only a couple of years ago after three break-ins. When insurance costs spiked, they were forced to make a change to stay afloat in challenging high street conditions. It’s a similar story for the breweries opening taprooms on quiet industrial estates.

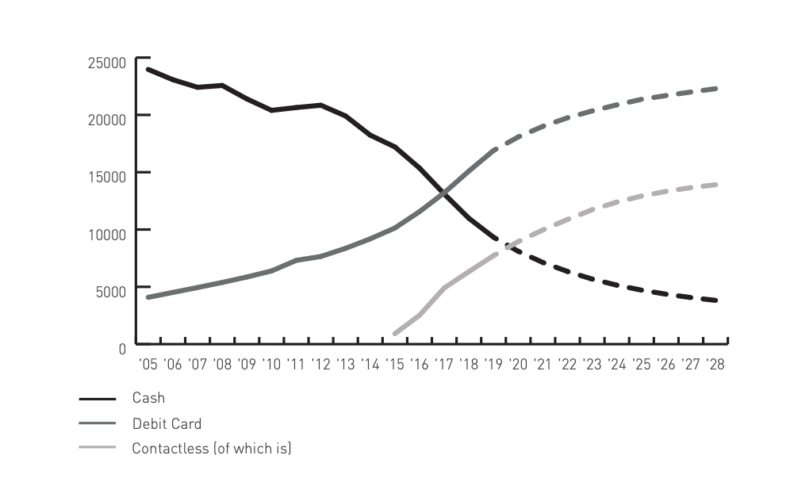

The decline of cash and rise of contactless payments has been rapid. Cash accounts for just 22% of all transactions, with over three-quarters of all transactions being made by some form of card payment (including e-commerce). By 2022, cash is forecast to be used for just one in ten payments.

You might expect politicians to welcome a trend that helps independent shops stay competitive, but alas, the shift to cashless payments has come in for heavy criticism. In the US, a number of cities have made it a legal requirement for shops to accept cash payment. Just yesterday, New York City’s council voted to ban card-only shops. Even San Francisco, home of $30bn point-of-sale provider Square, has called a halt to cashless retail.

The UK has so far been less knee-jerk, but there have been some concerning rumblings. The Access to Cash Review, a report funded by Link, the UK’s largest ATM provider, warned that Britain was “sleepwalking into a cashless future”. It described an ever so slightly over-dramatic future where young people would tap onto the tube with implants in their skin, while pensioners would struggle to use a debit card to buy a pint of milk.

Nonetheless, the report has been influential and Baroness Morgan, who was then Treasury Select Committee Chair, gave it her backing and called for a review and a potential ban on shops only accepting card or electronic payments. The Treasury too has committed to preserving access to cash in the UK.

Tradition may play a role. When it was hinted that Philip Hammond wanted to abolish the penny, a medium of exchange that serves no purpose, there was a substantial backlash. At one point former Treasury Permanent Secretary Lord Macpherson launched a campaign to save it. He tweeted, somewhat hysterically that “Only banana republics don’t have a coin representing the lowest denomination of their currency” and “To abolish penny would be to give into inflation and to trash 1000 years of history”.

In fairness, most of those who worry about the decline of cash are not clinging to a nostalgic view of ‘hard money’. They care more about the unbanked, people who can’t make card payments because they don’t even have a bank account. It’s a valid concern, but banning cashless retail will do next to nothing to help them.

When New York City banned card-only retail, a trade union posted “This critical bill will ensure everyone can shop or eat at any store in our city.” If only that were true. In reality, most card-only shops sell almost exclusively to better off customers anyway. Being unable to buy a ⅓ of a pint of an 11% Imperial Stout from Europe’s premier taproom isn’t a major worry for the unbanked. Likewise, the financially excluded tend not to pay £3 for a flat white in an Islington coffee shop.

Restricting card-only retail won’t do much either to slow the decline of cash. It may simply mean that independent bricks-and-mortar retailers lose market share even faster to online businesses like Amazon.

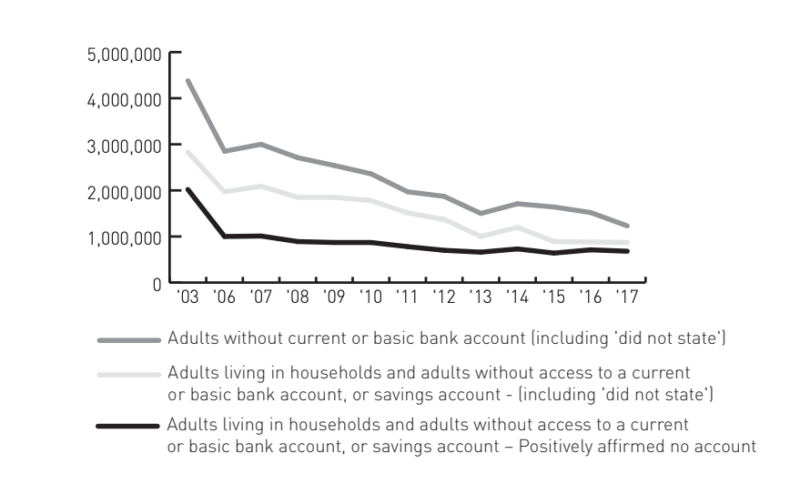

Banning card-only retail is a bit like treating the least consequential symptom of a serious illness. Instead of expending massive effort on making life a tiny bit less difficult for the unbanked, the overwhelming focus should be on getting them banked. On a positive note, there has been substantial progress in the last decade, with the unbanked population in the UK falling by around a million, according to the Financial Inclusion Commission.

Those who do remain unbanked face serious problems: they pay more for their utilities and struggle to build credit. But banning card-only shops won’t change that.

Encouraging competition and innovation in the banking sector could, however, be part of the long-term solution. Most of the unbanked have at one point had bank accounts, but abandoned them. With unplanned overdraft fees at one point being four times costlier than payday loan charges, it’s easy to see why.

Open Banking-enabled fintechs are addressing the problem. For instance, apps like Pockit are directly catering to the unbanked and Monzo now allows you to open a bank account without a fixed address. Better data, including from rental payments, will also allow the unbanked to build credit quicker and access finance.

Instead of scapegoating card-only retailers and trying to override long-term shifts in consumer demand, governments should focus on the failures of traditional finance providers and enabling a new wave of innovators to meet the needs of the unbanked.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.