Markets are efficient. In today’s climate of rising anti-capitalism, this proposition might be dismissed out of hand.

Yet, try as people have over the past 250 years, no alternative mechanism for allocating resources – whether Soviet communism, Yugoslavian self-management or British 1970s democratic statism – have been able to match the creative and productive power of decentralised exchange among free individuals.

Financial markets offer the most captivating example of the power of markets, for two reasons. Firstly, they provide a venue for virtually every commodity, now and in the future, to be traded in accordance with people’s desires and appetite for risk. Secondly, they constitute a venue for the swift exchange of assets: if one is prepared to sell at a reasonable price, one can be sure that a buyer will turn up. Reasonable means whatever the market will bear. The market being every other participant in exchange.

Economists are wont to argue under the assumption of perfect markets. They thereby open themselves up to the challenge that markets regularly exhibit glaring imperfections. New and unexpected information may trigger massive selloffs, temporarily halting liquid exchange. Transaction costs prevent small firms from raising capital on the open market. But there is no argument that market prices at any given time provide as accurate a picture of the present state of the world as is humanly achievable.

This is not an article of faith but an empirical fact validated time and again by finance academics. Studies have repeatedly shown that beating the market is not a science but a statistical aberration. Some 90 per cent of fund managers fail to outperform their benchmarks. It is hard to do better than the market once; it is nearly impossible to do so repeatedly. This is why an ever greater share of investors’ money is giving up on the chimeric quest to outperform and is instead being put into passive (index) funds.

As the idea of efficient markets has caught on, active fund managers, who market themselves as astute stock pickers, have struggled. Theirs are the most strident voices warning against the growth of index funds. They argue that a world of passive investment is a world of dumb money in which the role of markets in price discovery – finding out and transmitting changes in the value of the capital stock and the future returns on investment – will be stunted.

But this is setting up a straw man. No one is arguing that there ought to be no active funds. Rather, what the evidence suggests is that most active managers are net value destroyers and should therefore be doing something else. But there is a role for the Warren Buffetts, the George Soroses and the Cliff Asnesses of this world. The first trading on value, the second on macroeconomic events and the third on temporary momentum, they all help the market to decipher and digest the changing state of the world.

In a recent report on the state of UK asset management, the FCA worried about an absence of price competition among active managers: they all appeared to offer similar levels of charges.

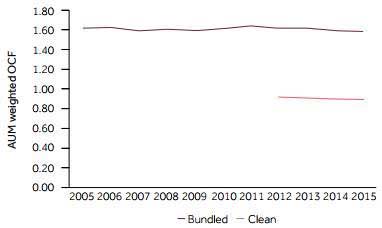

Fig. 1. Trends in fund charges for actively managed funds

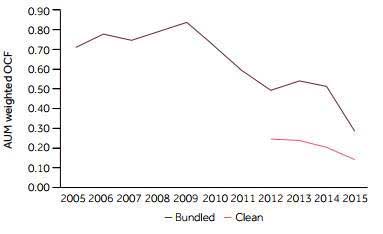

The regulator did acknowledge, on the other hand, that index fund charges have steadily declined over the past decade.

Fig. 2. Trends in fund charges for index-tracking funds

An impartial economist might well look at the two charts above and determine that passive funds, because they simply track the market, compete on price (fund charges), whereas active funds compete on quality (manager skill). This is intuitively plausible because the value proposition of passive management is its low cost, whereas the argument for active management is its alleged ability to outperform the market.

But the FCA won’t have it. To them, price uniformity looks insufficiently competitive if not anti-competitive, and thus requiring some form of intervention. Indeed, the FCA report reads like a textbook case of missing the wood for the trees. They examine a market which has been revolutionised by the findings of portfolio theory; where fund charges have steadily dropped since the 1970s; with record numbers of retail funds flowing in; with ever lower transaction costs and increasing liquidity; a market that is now being transformed by online platforms; and they conclude that competition is lacking because actively managed funds tend to charge the same. The irony is that the perfectly competitive model of economics textbooks says that, in equilibrium, all will charge the same price.

Marx famously said that philosophers seek to understand the world, but the point is to change it. For economists, the opposite is true. They seek to change the world but the point is to understand it. And the great fact about modern financial markets is that they are efficient and delivering ever greater prosperity to an expanding number of people, all around the world.