Why did the British vote for Brexit? This question has attracted a lively debate over the past year. For some, the vote was driven by concerns over sovereignty, a desire to restore effective control over national laws and institutions. For others, the vote was driven far more by immigration, a desire to reduce it and — in a different way — restore control over borders. But is this the whole story?

In a new book on the Brexit vote, published this week, we present a wealth of evidence on what delivered the historic vote. Our data come from representative national surveys with over 150,000 voters, conducted over the past decade. Last June we also contacted a national panel of voters before and immediately after the referendum to ascertain whether they had voted Remain or Leave — and, crucially, why.

From the data, it would seem that Brexit was not driven by any single factor, but rather reflected “a complex and cross-cutting mix of calculations, emotions and cues”. That said, immigration was key.

To really make sense of the Brexit vote we need to adopt a long-term view. Over the past decade, large majorities of our survey respondents consistently told us they wanted to see immigration into Britain reduced. The perception that historically unprecedented levels of net migration posed serious economic, security and cultural threats was widespread.

If people felt negatively about immigration, how it had been managed, and thought Britain had lost control of its economy to the EU then — long before June 2016 — they were already hostile toward the EU and prepared to terminate UK membership.

Many of those who would later vote for Brexit had concluded that the governing parties — Labour and Conservative alike— had failed to manage immigration competently. Therefore, many of the forces that led to Brexit were operating long before the referendum was held.

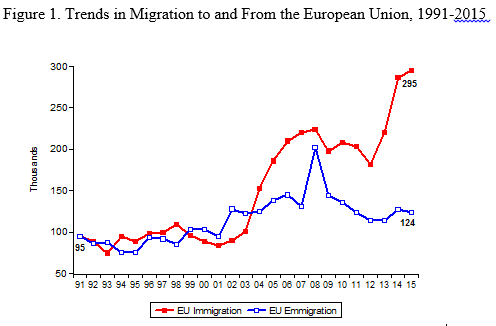

Figure 1 shows that in recent years, the number of EU nationals arriving in Britain escalated sharply and concerns about immigration rose to the top of the political agenda. Then, in 2015, Angela Merkel’s decision to admit large numbers of refugees into the EU fuelled a sense among voters that established politicians, regardless of party, were failing to manage and, indeed, were indifferent to, an issue about which they cared very deeply.

As Britain headed towards the referendum, many people calculated that Brexit would be economically risky, both for the country and themselves. But they also concluded that, by leaving the EU, Britain would be better able to control its borders, counter terrorism and prevent the loss of sovereignty to the EU. These voters were concerned about their national community, not just economic self-interest. They eventually opted for Brexit in huge numbers.

Our findings show how the 2014 European Parliament elections and the 2015 general election both played an important role in setting the stage for Brexit. These contests contained clear signposts for what was to follow. Support for the UK Independence Party (UKIP) reflected negative judgements about how the main parties had performed on immigration, as well as other major issues such as the economy and the NHS.

In particular, UKIP played a key role in mobilising disaffected voters who felt deeply anxious over immigration, with this sentiment being reinforced by feelings of being “left behind” because their personal financial circumstances had not kept pace with economic conditions in the country as a whole. But immigration was key. Had these voters not been mobilised and galvanised around an anti-EU and anti-immigration message, then it is highly unlikely that they would have turned out in great numbers at the referendum.

On 23 June 2016, these dynamics came together to deliver the Brexit decision — a collective choice that reflected a complex mix of calculations, emotions and cues. Some of these factors, such as the above concerns about immigration and a loss of control to Brussels, had been baked in years ago.

If people felt as though they had been left behind, they were much less likely to view Brexit as a risk — perhaps they felt they already had little to lose. Many of these calculations were made well before the referendum campaign began.

Other factors that mattered, however, were more recent. Immigration was clearly potent but Leavers were divided on how to approach the issue. Some Leave strategists believed that while a heavy focus on immigration would attract working class UKIP voters it would alienate politically correct middle-class people needed to secure a majority. Not emphasising immigration posed the opposite risk.

But, in the end, our analyses reveal how the “Divided House of Leave” turned out to be a key strength, allowing the rival Leave campaigns to win over different groups of Leave-minded voters. When, from 1 June, all of the Leave camps put the pedal down on the emotionally resonant issue of immigration, they were very much in tune with the core driver of anti-EU sentiments, and middle-class Eurosceptics were willing to board the Brexit train.

Where did Remain go wrong? This brings us to the role of “cues”—the influence exerted by competing politicians. Cameron and the Remainers recognised that many voters were risk averse and concerned about the economic effects of Brexit.

“Project Fear” carpet-bombed voters with thousands of messages from eminent economists, major public officials and pop culture celebrities about the economic disasters that would be precipitated by leaving the EU. Most famously, President Barack Obama flew to London to caution voters that if Britain exited the EU, it would have to “go to the back of the queue” if it wanted a trade deal with the US.

Attempting to frighten voters into a Remain vote was not necessarily the wrong strategy. Those who saw Brexit as a significant risk were significantly more likely to turn to Remain. But it is also worth dwelling on how people saw the campaign. Although a plurality of voters felt negatively about both sides, a larger number saw Leave — not Remain — as more positive, honest, clear about their case and as having understood people’s concerns.

While more than twice as many people saw Leave rather than Remain as representing “ordinary people”, more than twice as many also saw Remain rather than Leave as representing “the establishment”. And many people felt that the establishment was decidedly unresponsive to the concerns of ordinary people

Our survey data show that in the final week of the campaign, voters had responded strongly to both messages. Leave was close to winning because it had immigration but it was close to losing because Remain had the economy. So what pushed Leave over the line?

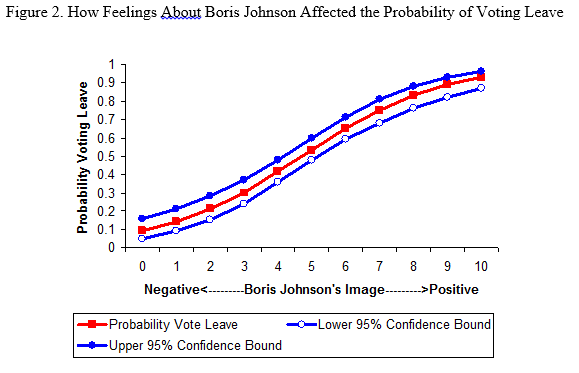

This is where leader cues mattered. As shown in Figure 2 below, our analyses reveal that voters’ feelings about Boris Johnson had strong effects on the probability that voters would opt for Brexit. Boris was a powerful messenger in “respectable” parts of the electorate that the toxic Farage could not reach.

Yet Farage, too, did have a significant positive effect on the Brexit vote, contrary to what some claim. Neither Cameron nor Corbyn were nearly as effective for Remain. Leader cues were much stronger on the Leave side, with Johnson and Farage appealing to two different audiences, both of which were needed to make a Brexit decision a reality.

Yet another advantage for Leave emerged in our surveys — its anti-immigration and anti-EU message had an emotional appeal that Remain’s economic pessimism could not match. Weeks before the balloting, we calculated that Remain might be favoured across the electorate as a whole and still lose because Leave supporters were more likely to show up at the polls. Subsequent analyses show that this “enthusiasm gap” was indeed real.

In conclusion, the story of why Britain voted to leave the EU is straightforward. Propagated by an unlikely pair of effective messengers, Leave’s “Take Back Control” message harnessed the motive power of immigration, an emotionally charged issue that had been baked into British psychology long before the vote was even called.

These immigration fears, hitherto confined to the politically incorrect margins, not abstract concerns about a “democratic deficit” that required rescuing UK sovereignty from Brussels bureaucrats, do much to explain why Britain voted for Brexit.