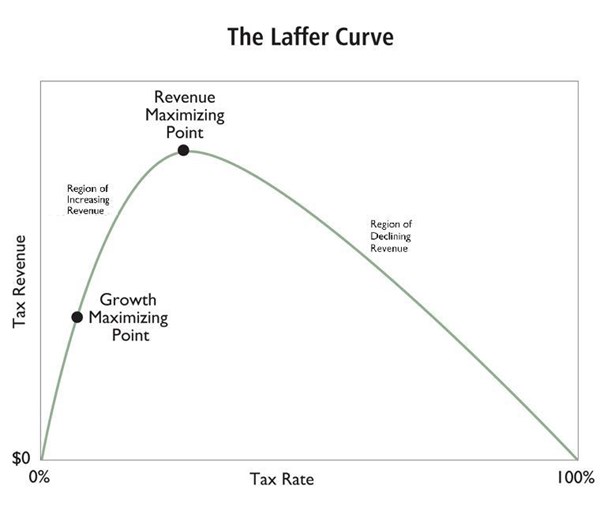

Since there’s a big debate about whether there should be tax cuts and tax reform in the United States, let’s see what we can learn from abroad. And let’s focus specifically on whether changes in tax policy actually produce “revenue feedback” because of the Laffer Curve.

In other words, if tax rates change, does that incentivize people to alter how much they work, save, and invest, thus changing the amount of taxable income they earn and report?

I’ve written about how the Laffer Curve has impacted revenue in nations such as France, Russia, Ireland, Canada, and the United Kingdom.

Now let’s go to Africa. In a column for BizNis Africa, Kyle Mandy of PwC explicitly warns that South Africa is at the wrong spot on the Laffer Curve.

At the time of the 2017 Budget in February, a number of commentators, including myself, warned National Treasury and Parliament that the tax increases announced in the Budget, particularly on personal income tax, would likely push tax revenues very close to the top of the Laffer curve, i.e. the point at which tax revenues are maximised and beyond which tax rate increases will actually result in a decrease in tax revenues.

Before continuing with the article, I can’t resist making an important point. The author understands that it is a bad idea to be on the downward-sloping part of the Laffer Curve. As he points out, that’s when tax rates are so punitive that “tax rate increases will actually result in a decrease in tax revenues.”

That’s correct, of course, but it’s almost as important to understand that it’s also a very bad idea to be at the “top of the Laffer Curve.” As noted in a study by economists from the Federal Reserve and the University of Chicago, that’s the point where economic damage is so great that a dollar of tax revenue can be associated with $20 of damage to the private sector.

Now that I got that off my chest, let’s look at some of the details in the article about South Africa.

The evidence…suggests that, in the current environment, South Africa has maximised the tax revenues that it can extract from its citizens and has possibly even gone past that point and is now on the downward slope of the curve. Why do I say this? The last few years have seen significant tax increases… These tax increases saw the main budget tax: GDP ratio increase from 24.5 per cent in 2012/13 to 26 per cent in 2015/16, primarily led by increases in personal income tax. However, since then the tax:GDP ratio has stalled at 26 per cent in both 2016/17 and in the revised forecast for 2017/18. It is not unreasonable to expect that the tax:GDP ratio for 2017/18 may fall below 26 per cent in the final outcome. The stalling of the tax:GDP ratio comes despite significant tax increases in each of 2016/17 and 2017/18 which were expected to deliver ZAR18 billion and ZAR28 billion of additional tax revenues respectively.

Once again, I can’t resist the temptation to interject. That final sentence should be changed to read “the stalling of the tax:GDP ratio comes because of significant tax increases.”

Mr. Mandy concludes his column by warning that the current approach is leading to bad results and noting that further tax hikes would make a bad situation even worse.

…the South African Revenue Service has acknowledged that it has seen a decline in levels of compliance. …So what does all of this mean for tax policy and fiscal policy generally? Simply put, National Treasury have been placed in an invidious position. Increasing taxes further in the current environment could be self-defeating and result in a decline in the tax:GDP ratio. This risk is particularly prevalent insofar as further tax increases in the form of personal income tax are concerned. Increasing the corporate tax rate would further dent investor confidence and economic growth.

The good news is that even South Africa’s government seems to realise there is a problem.

Here are some excerpts from a recent story.

Finance minister Malusi Gigaba has received President Jacob Zuma’s stamp of approval for an inquiry into tax administration and governance at the South African Revenue Service (Sars). According to the Medium-Term Budget Policy Statement (MTBPS), tax revenue is expected to fall almost R51 billion short of earlier estimates in the current fiscal year …The probe also comes amid warnings that further tax hikes could be futile and may even result in a decline in the country’s tax-to-GDP ratio. … National Treasury has introduced various tax hikes over the past few years. The main budget tax-to-GDP ratio increased from 24.5 per cent in 2012/13 to 26 per cent in 2015/16, mainly as a result of higher effective personal income tax rates. But the tax-to-GDP ratio has subsequently stalled at 26 per cent in 2016/17 and in the latest 2017/18 forecast and it is not inconceivable that the final outcome for the current fiscal year could fall below 26 per cent … Gigaba seems to be aware of the dangers of additional tax hikes and warned in his MTBPS that it could be “counterproductive”.

I’m glad that there’s a recognition that higher taxes would backfire, but that’s not going to fix any problems.

The pressure for higher taxes will be relentless unless the South African government begins to control spending. The government should adopt a constitutional spending cap, which would alleviate budget pressures and create some “fiscal space” for lower tax rates.

But I’m not confident that will happen, particularly if the International Monetary Fund gets involved. Desmond Lachman, formerly of the IMF and now with the American Enterprise Institute, writes that the country is in trouble.

South Africa is in trouble. Per capita income has been in decline for several years and its economy is in recession for the second time in eight years. Unemployment remains at over 27 per cent . Meanwhile, the rand is floundering on the foreign exchange market … In view of the favourable global economic environment, the country’s predicament is even more troubling. Interest rates have rarely been lower and capital flows to emerging markets have seldom been stronger. … If South Africa’s economy is performing poorly in this environment, it will probably struggle even more when central banks start to normalise their interest rate policies and when the global economic environment becomes more challenging.

He has the right description of the problem, but I’m worried about his proposed solution.

IMF assistance can hasten restoration of confidence. … An IMF programme would not be popular politically within South Africa but the government does not appear to have any realistic alternative.

Simply stated, the IMF has a very bad track record of pushing for higher taxes.

That doesn’t necessarily mean its bureaucrats will push for bad policy in South Africa, but past performance sometimes is a good predictor of future behavior.

For what it’s worth, the IMF is fully aware that the burden of government has been increasing. Here’s a blurb from the most recent Article IV report on South Africa.

During the past few years, the share of both revenues and expenditures continued its rising trend. The size of general government in South Africa is one of the highest among international peers at a similar level of development. Primary expenditures rose by 1.5 percentage points of GDP between 2012/13 and 2015/16, owing primarily to public enterprise-related transfers (0.8 percent of GDP, including a 0.6 per cent of GDP equity injection for Eskom in 2015/2016) as well as relatively generous wage agreements combined with an increase in consolidated government employment (0.3 percent of GDP). In recent years, including the 2017 budget, higher personal income taxation has been the main tax policy instrument to collect revenue combined with higher excise rates.

And here’s a section of the data table showing the expanding burden of both taxes and spending.

Unfortunately, the IMF never says that this growing fiscal burden is a problem. Instead, the focus is solely on the fact that spending is higher than revenue. In other words, the IMF mistakenly fixates on the symptom of red ink instead of addressing the real problem of excessive government.

So if the bureaucrats do an intervention, it almost certainly will result in bailout money for South Africa’s politicians in exchange for a “balanced” package of spending cuts and tax increases.

But the spending cuts likely will be either phoney (reductions in planned increases, just like they do it in Washington) or will quickly evaporate. But the higher taxes will be real and permanent. Just like in most other nations where the IMF has intervened. Lather, rinse, repeat.

Speaking of misguided international bureaucracies, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development already has been pushing bad policy on South Africa. The bureaucrats even brag about their impact, as you can see from this Table in the OECD’s recent Economic Survey on South Africa.

The OECD is happy that income tax rates have increased and that there’s more double taxation on dividends, but the bureaucrats are still hoping for a new energy tax, expansion of the value-added tax, and more property taxes.

They must really hate the people of South Africa. No wonder the OECD is known as the world’s worst international bureaucracy.

I’ll close by noting that the country’s problems are not limited to fiscal policy. The country is only ranked 95th by Economic Freedom of the World. And it was as high as 46th in 2000.

Instead of pushing for higher taxes, that’s the problem the OECD and IMF should be trying to fix. But given their track record, that’s about as likely as me playing centerfield next year for the Yankees.

This article was originally published on FEE.org. Read the original article.