On the face of it, Donald Trump’s astonishing victory should be good news for Britain, post-Brexit.

The UK will no longer be “at the end of the queue” for trade deals with the US, as President Obama warned, since all the other deals in that queue will now be dropped, especially the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership which the European Union has been laboriously negotiating.

What Britain will learn is that “trade deals” are not the same as actual trade, and that President Trump’s idea of a deal could differ substantially from the more free-market end of the Brexiteer spectrum. His thinking will be closer to that of Nigel Farage than to David Davis or Liam Fox.

Beyond bilateral trade, the Trump era promises to make it even more important for Theresa May’s Government to nurture a close partnership with the rest of Europe even as it cosies up, as it surely will, to its old special relationship.

Trump in the White House, and Republicans still in control of both houses of Congress, is likely to pose several challenges for the British Government:

1. NATO

Britain has long argued that NATO should be the main focus of European security policy, not any EU army or joint forces. But during his campaign, Mr Trump disparaged NATO and its members, threatening to downgrade or even disown it if member countries failed to spend enough on defence.

Britain has done better on that measure than most, but its armed forces are still looking threadbare. A Trump presidency will pile pressure on Britain to spend more on defence and could weaken NATO markedly.

2. Russia

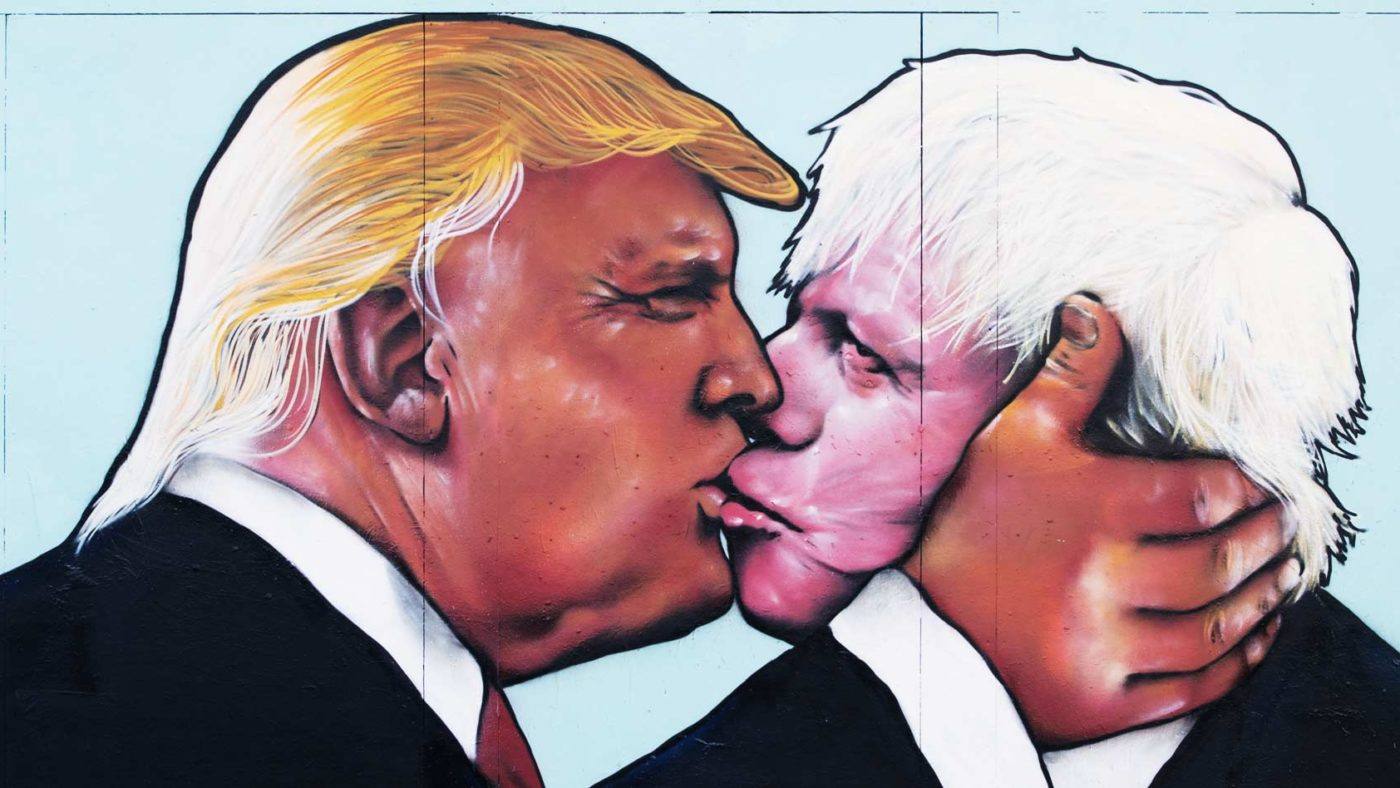

Britain has taken a firm line on Russia’s intervention in Ukraine and its annexation of Crimea, and its foreign secretary has claimed Russia should be prosecuted for war crimes for the bombing of Aleppo. Boris Johnson even incited demonstrators to protest outside the Russian embassy.

While President Trump is unlikely to become bosom buddies with Vladimir Putin, he is nevertheless likely to seek compromises that could well make Britain feel distinctly uncomfortable. British policy is closer to that of Angela Merkel than Donald Trump.

3. Iran

As with Russia, Britain will find itself on the opposite side from President Trump, at least as a starting point. The UK was one of the prime movers behind the Iran nuclear deal which Trump said he would either scrap or revise.

He may not stick to that position, but one thing is clear: he, and the Republicans in Congress, will be closer to Israel’s position on Iran than President Obama was.

4.Climate change

This will please some elements of the UK Government, and many Brexiters, but not all: it is pretty certain that President Trump and the Republican Congress will scrap the little that the US had done to meet global climate commitments. Efforts to mitigate climate change will continue at state level, but no federal effort can be expected.

5. World trade

Finally, leaving aside the potential for any bilateral US-UK free-trade pact, the climate in Washington is now going to be hostile to all global trade liberalisation talks and possibly even some existing deals.

We cannot know in advance how protectionist the US is going to become. But we can know that Britain, as a trading nation wanting to buy and sell freely with the whole world, is likely to be a loser if protectionism really does become the flavour of the era.

At least the traditionally close relationship between our intelligence services and those of America can still be depended upon. But it is not going to be a comfortable or predictable ride.

Theresa May and Boris Johnson had better mean it when they say that post-Brexit Britain will have a great new partnership with our European friends and neighbours. We’re going to need it.