A series of bombshell polls over the weekend suggested that the upcoming European elections in the UK will be marked with a high degree of fragmentation – and the possibility of major political realignment.

YouGov’s polling suggested five parties would win more than 10 per cent of the vote – the Brexit Party (34 per cent), Labour (16 per cent), the Liberal Democrats (15 per cent), the Greens (11 per cent), and the Conservatives (10 per cent). This would put the combined Conservative and Labour vote share at 26 per cent for the European elections, down from 47 per cent in 2014. Even the polling for Westminster elections, where voters are less likely to indulge in protest voting, puts Labour and the Tories together at just 48 per cent — down from 84.5 per cent in the 2017 election, which was widely heralded as the return of two-party politics.

This fragmentation largely reflects frustration from Leavers and Remainers alike at the way the two main parties have handled Brexit. As Matt Singh recently argued on CapX, it remains to be seen whether it will become a long-term trend.

However, a splintered political landscape is far from a UK-only phenomenon.

In Germany, both the centre-right Christian Democrats and the centre-left Social Democrats have seen their support hollowed out by the pro-EU Greens and the nationalist Alternative fur Deutschland (AfD).

The political landscape in the Netherlands has become so diverse that the process of fragmentation elsewhere is often referred to as ‘Dutchification.’

And in the recent Spanish elections, the share of the vote won by the two traditional ‘big’ parties was just 45 per cent – down from 84 per cent in 2008. In total, there are seven European countries where four or more parties won over 10 per cent of the vote in the most recent legislative elections – Germany, the Netherlands, France, Spain, Italy, the Czech Republic and Finland.

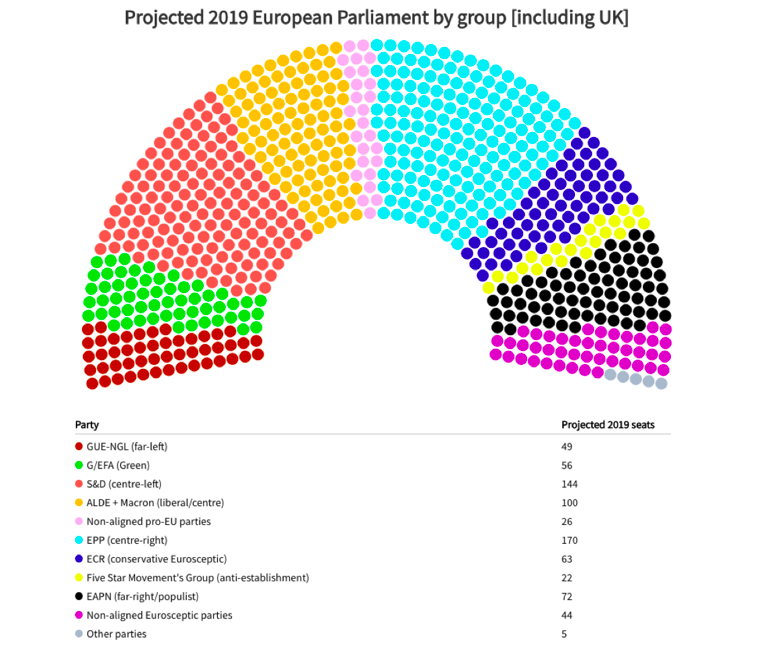

As we set out in a recent Open Europe briefing, the upcoming European Parliament elections look set to elevate these divisions to the European level. In a reflection of political developments in many member states, the Parliament as a whole is expected to become increasingly fragmented and polarised, with mainstream centre-right and centre-left parties losing ground to liberals, greens and nationalists. And this fragmentation goes beyond the diverse array of official political groups illustrated in the chart below, as many of the groups are themselves broad churches beset with internal divisions.

This development will have consequences for the functioning of the EU. The ‘Grand Coalition’ of the centre-right European People’s Party (EPP) and the centre-left Socialists and Democrats (S&D) is set to lose its combined majority, for the first time ever. In 2014, they had a majority of 34; Politico’s current projections suggest they will be 60 seats short.

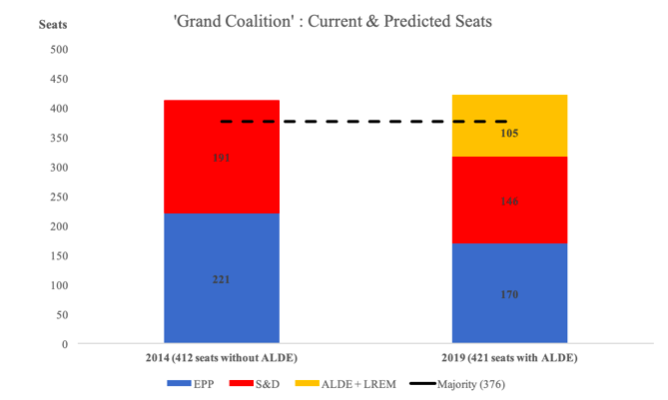

The significance of this goes beyond the merely symbolic – between them, the EPP and S&D carried 74 per cent of votes on legislation in the last term of the Parliament. They will most likely have to co-opt the liberal group ALDE, together with the MEPs from French President Emmanuel Macron’s La Republique en Marche (LREM), into a new three-party legislative coalition.

As illustrated below, this new coalition will barely have a larger majority than the old one, with ALDE’s gains cancelled out by considerable losses for the two larger parties.

Meanwhile, there is also set to be a significant realignment of the Parliament’s Eurosceptic contingent. The European Conservatives and Reformists group (ECR), which nominally represents a moderate and constructive brand of Euroscepticism, is set to be eclipsed by the more nationalist and populist European Alliance of Peoples and Nations (EAPN), a new bloc set up by Italian Deputy Prime Minister Matteo Salvini.

This newly fragmented European Parliament will be a difficult partner for the European Commission and Council. Although pro-EU forces still have an overall majority, they will need to work more closely across party lines to get legislation through. This in turn may exacerbate the ‘establishment vs anti-establishment’ dynamic of the current parliament, by amplifying populist claims that the mainstream parties are all the same. We should also expect votes to be closer than in the last five years, during which only 10 per cent of votes were passed by a majority of less than 50 votes.

Across Europe, politics is becoming more diverse and multi-dimensional. Traditional left-right divisions are increasingly becoming eclipsed with cross-cutting questions of culture and identity, particularly immigration and climate change. While it has the advantage of giving voters a wider range of choices, political fragmentation has already made several European countries much harder to govern. That problem now looks likely to be exported to the institutions of the EU, and – despite Brexit – to the UK as well.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.