Many people are taking 48 hours away from Twitter to support a call from Jewish civic voices for allies to challenge the platform’s weak response to an anti-Semitic diatribe by the grime artist Wiley. Several of his tweets were removed, eventually, while others have been left online. The account has been temporarily suspended, but not removed.

As New Statesman political editor Stephen Bush set out in his nuanced statement of support for the symbolic boycott, there is plenty of evidence to show that the platform has not acted sufficiently against anti-Semitism. There is rather less evidence for the hunch expressed by some supporters of the campaign, such as the comedian David Baddiel, that other forms of racism are dealt with more rapidly. Rather, Twitter’s failures on anti-Semitism form part of its broader systemic failure to deal with racism on the platform.

Indeed, in the Twitter rules, there is a disparity in the other direction. Unusually, Twitter’s policies on hate speech now give stronger protection to members of religious groups than to ethnic groups, though few people are aware of this.

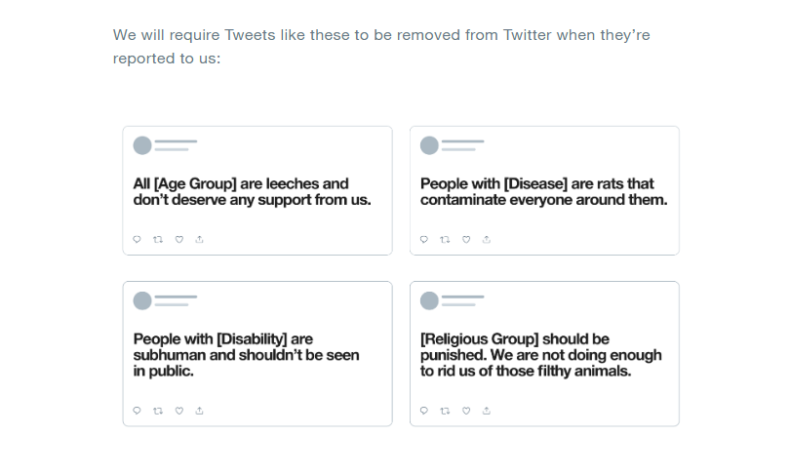

This results from a change of the platform rules against ‘hateful conduct’ a year ago, Twitter gave examples of the tweets (see below) which had been within the rules, but which would now fall outside of it. Many would have been surprised to hear that these types of tweets had previously been allowed. The rules prohibited the direct abuse and harassment of individuals, but had left open these types of generic hate statements

Surprisingly, Twitter has still not extended this approach to racism against ethnic groups, though they have been extended to disability and age this Spring. So it is now against the Twitter rules to tweet “the Jews are vermin” or “the Muslims are vermin” yet “the blacks are vermin” remains within the rules.

In a summer when corporations are making commitments to anti-racist solidarity, with the jury out about what concrete steps will follow, it is difficult to find a more jaw-dropping example of a gap between rhetoric and practice than Twitter pinning the #blacklivesmatter hashtag to its own profile, while still being unable to decide, this summer, whether or not it wants to prohibit dehumanising racism against black people on the platform. (Twelve months on, a global “working group” is looking into the “tricky dilemmas” of extending the policy to ethnic groups.)

On anti-Semitism, Twitter already has the rules in place, but that is not enough if it does not enforce them. The core problem is the lack of commitment, culture or capacity to uphold the rules that it has.

There has occasionally been some incremental progress. Social media platforms including Facebook and Twitter did take issues of online hate crime more seriously after the Christchurch massacre offered a clear example of a link between online hate and murder. Reactive decisions have been made: for example, the commentator Katie Hopkins was removed after one NGO, the Centre for Countering Digital Hate, produced a dossier of persistent rule violations. That somewhat unusual decision did not indicate a sustained effort to shift the boundaries of the platform. Many more virulent and violent voices than Hopkins or Tommy Robinson remain on the platform, such as Mark Collett, the overtly pro-Nazi BNP youth officer who fell out with Nick Griffin because he saw the BNP as too moderate.

I supplied Twitter with examples diligently collected by civic-minded users of the most virulent users who had been banned dozens of times, yet who were openly mocking the platform for its inability to enforce its rules. I had evidence of one user being banned 17 times in six months under user names including ‘Smelly Jew’, ‘Fetid Jew’ and so on. When I submitted reports of his sarcastic appeal for followers to return – using the hashtag #myfirsttweet – the response came back that the system could not see a violation of the rules. Twitter did act on some of the worst repeat offenders, when the information was collated externally by volunteers. But, since the Covid pandemic, the insufficient resources put into assessing reports have been considerably more over-stretched than usual. Users find they may not hear back for many weeks, if at all, about reports that are submitted. Sometimes tweets or accounts get removed, and sometimes they don’t.

‘Cancel culture’

The Wiley case also helps to illuminate the noisy debate about “cancel culture”

A principled opposition to “cancel culture” would appear to entail an argument that neither Wiley, nor David Starkey after his recent overtly racist interview, should face professional consequences for promoting prejudice and hatred within the law. It is possible to argue this in a debating society – but only a handful of free speech libertarians hold this position in practice. The considerably more plausible argument about “cancel culture” is that there is an over-stretch – that the boundaries are in the wrong place. However, the key to an “overstretch” argument to set out a principled argument about where the boundaries should be – and that is currently largely absent from this debate.

At the same time, the opponents of hate speech also face a challenge in defining boundaries that protect free speech, while excluding hateful conduct. There is a tendency to underestimate the reputational damage that can be done to anti-prejudice norms through over-reaching.

On the other hand, the defenders of free speech face a public challenge in defining the boundary (if any) of the hate speech they agree is indefensible. This is essential if the claim about overstretch is to be given any content.

Toby Young of the Free Speech Union ducks this question – in arguing that Wiley should be offered the chance to hear the “opposing” argument, to reflect on it, and to apologise. Young’s argument is that “everyone makes mistakes” and that it is “disproportionate” to face professional consequences “merely for expressing an opinion, however unsavoury and offensive”.

https://twitter.com/toadmeister/status/1287462345703403523

Wiley had already responded to this point before Young made it – responding for calls to desist and apologise by tweeting “Wiley needs help because he has clocked who the real enemy is? Lol”. That is one of the tweets that has not been removed by Twitter.

It would seem clear that Young’s holding position no longer holds. There is a good case for a process for sincere rehabilitation – though a good test is whether members of the targeted group believe an apology is sincere or insincere, and whether there is any serious effort to make amends. But that point ducks the central question of whether it is proportionate to face consequences for hate speech.

So how do we start a conversation about where the boundaries should lie?

The incitement to violence is not covered by free speech – and falls outside the law.

Free speech within the law includes speech which dehumanises people as an existential threat. If you tweet “the Jews [or Muslims or Blacks] are vermin – we should not want these filthy animals in our country” then most people will think it is appropriate for the loss of public reputation to come with sanctions. There are jobs – such as being a policeman or teacher – that are incompatible with publicly expressing these views, though how far this extends across a spectrum of wider range of organisations and roles may be a matter on which views differ.

Any mainstream political party would be expected to ditch a parliamentary or council candidate who expressed such a view. This should cross the “deplatforming” threshold for removing social media accounts. Calls to remove Wiley’s MBE seem valid, given the purpose of symbolic public honours, which is why there is a forfeiture process, albeit a rather opaque one.

Dehumanising speech violates the principle of equal citizenship – if some people put up with a level of personal abuse or harassment that others do not face in order to participate at all. I would like to set a higher “civility test” for decency in public conversation. There is no right not to hear different opinions, nor any right not to be offended, but a conversation about a group should be a conversation which could continue if a member of that group walked into the room – and which they could reasonably expect to take part in. This is an important goal, but it is not one which can or should be pursued by deplatforming, but rather in the through challenge, persuasion and modelling the online behaviours that we want to see become norms.

Many people would agree that so-called “cancel culture” can sometimes go too far, yet that there are also times when institutions are too lax in protecting norms against hatred and prejudice. Might the Wiley and Starkey cases become an opportunity to move beyond a dialogue of the deaf between competing polemics? To make sense of the debate about free speech and hate speech, those involved need to look through both ends of the telescope – and start a more serious conversation about where the boundaries should lie and why.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.