When you conduct an economic study you measure a range of variables, but most of the time you can’t capture everything. You analyse the date you have collected, and find relationships, but if you aren’t careful there might be a variable you’ve omitted, which means that your correlations will be biased.

Some examples are obvious. Cigarette lighter purchases correlate with lung cancer 30 years later, but the link is obviously spurious: an omitted variable — smoking — causes both.

But others are surprising. Those who smoke have lung cancer rates 25 times higher than those who don’t smoke—can we say that smoking makes you 25 times more likely to get lung cancer? It turns out we can’t: the world is unfair and genetics have a huge role to play too. If you compare identical twins, the one who smokes is only five times more likely to get lung cancer than his non-smoking pair.

The fact that omitted variable bias pops up even in examples where you think you’ve controlled for everything should make us wary of concluding much from studies which compare a cross section of people or countries. People are extremely diverse. Even after you net out family income, job history, job sector, years of education, and degree studied, there’s a lot left unobserved.

When it comes to simple analysis, even on large pools of data, we should be sceptical of “naive empiricism”—the idea that the data simply speak to us and all we need do is listen. We often have compelling logical reasons to doubt what it’s saying. Naive empiricism sometimes tells you cigarette lighters cause cancer.

All this means that the Social Mobility Commission’s latest report, out today, should be taken with a pinch, or even a heap of salt.

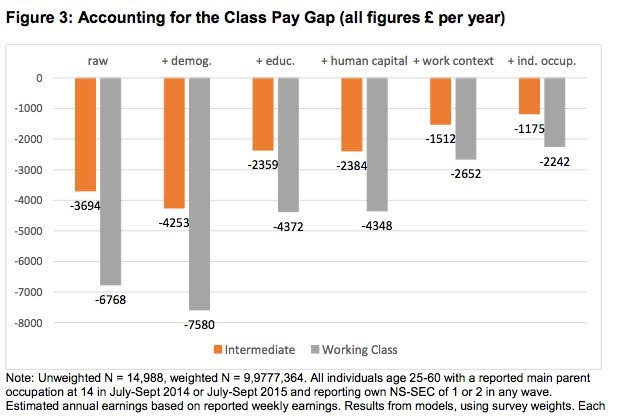

This report has found that those from working-class backgrounds will earn less in a given professional field. They note that this gap is still significant after they control for various observed factors. The ones they control for are among the most important ones; but look how even this limited array dramatically reduces or mediates the link between working-class background and pay. What would happen if we had even richer data?

Without actually having this extra data, though, and all other things being equal, we should still go on the best we have. The issue is that we have compelling logic, as well as evidence, that we will find “unobservables” that further reduce the gap—probably to roughly zero.

It would make no sense for firms to be biased against hiring working-class employees. It would only take one or two unbiased firms in each sector — or the likelihood of such a firm being set up — to compete for the under-priced, working-class talent, and their wages would be driven up until they were paid according to what they produced for the firm. This is no smarter for firms to do in normal sectors of the economy than it would be if a football club decided to exercises bias against working-class players.

Evidence frequently bears this argument out — I have catalogued it again and again. Those living in neighbourhoods with worse peers tend to do worse at school—but only because the people in those neighbourhoods were different to begin with, not because the peers made their grades worse directly.

Those with riskier jobs might look like they earn less — but they actually earn more than identical twins of theirs who don’t do risky jobs. Those with foreign names appear to get worse responses for their CVs — but not when their CVs are identical to natives. These unobserved factors are the key drivers in the results gathered.