Germany is a curious nation. Its history has involved constant metamorphosis. It has never stood still, and has never accepted a backseat within European politics.

Today’s Germany is piously democratic. There are checks and balances instituted in its constitution along with the power to challenge the government of individual Länder (federal states). Its politics are vibrant and broadly coalitionary; indeed, it is only in Bavaria where one party (Horst Seehofer’s CSU) leads a majority state government. After every election, the complexion of German political life can change dramatically, depending not just on whether the SPD or CDU leads the government, but on who leads the states, too.

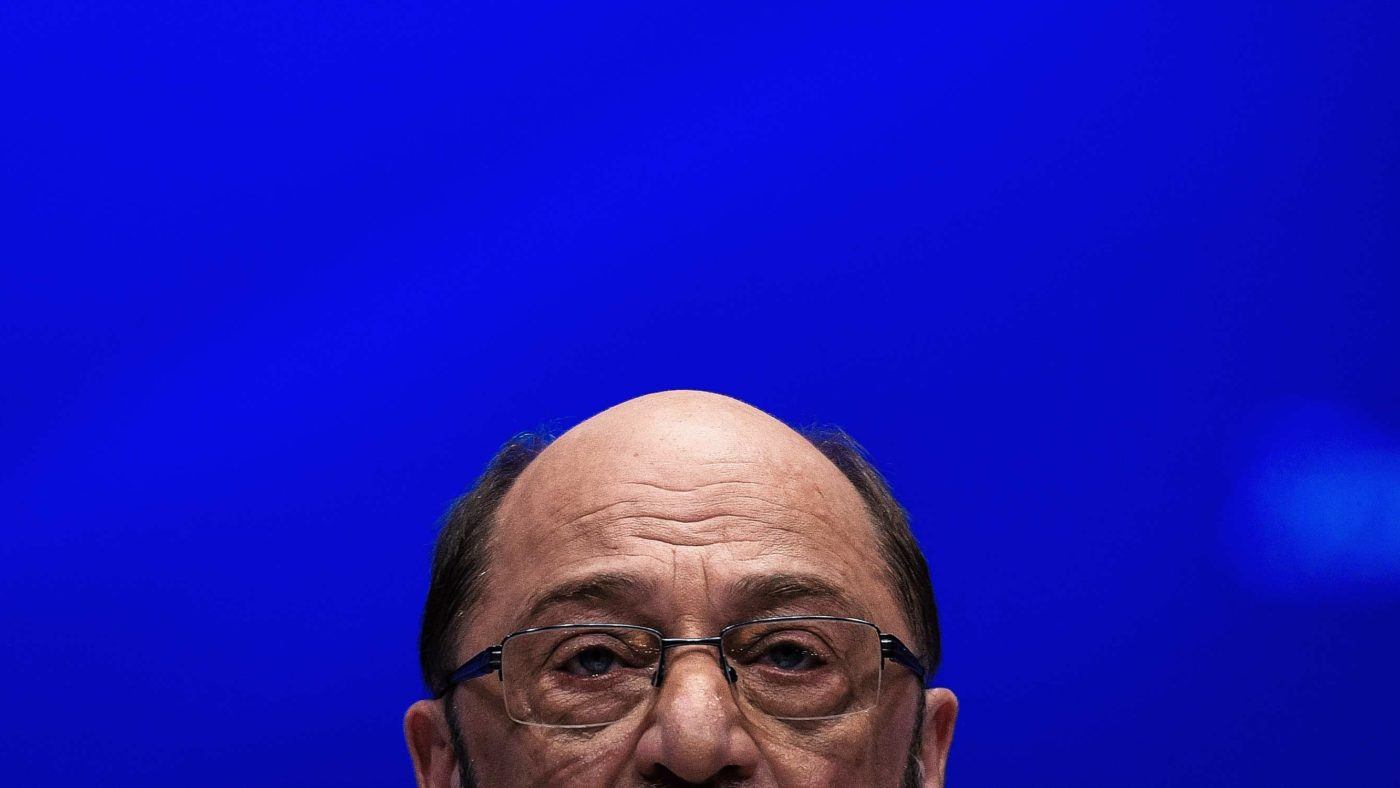

But despite suggestions that Germany is tiring of Merkel, and regardless of the final push from her nearest rivals, don’t expect any upsets this time around. Merkel’s CDU has been enjoying excellent results in state elections in the Rhineland, Saarland and in Schleswig-Holstein and polling suggests her party will storm to victory – the CDU are some 14 points ahead of the Social Democrats (SPD), headed by Martin Schulz.

It was thought Merkel had suffered permanent political damage following the welcome she has given to an unprecedented number of refugees. But upon examination of the fortunes of Alternative for Germany (the popularity of this small right-wing populist party could be seen as an indicator of public opinion towards Merkel’s immigration policy), whose early electoral successes have dramatically withered, it would seem fair to say that the chancellor has recovered any ground lost from her liberal immigration policies.

You can’t say the same for Martin Schulz, however. He did, for a moment this year, look like he might pose a serious challenge to Merkel. Not any more. The SPD is languishing in the polls and, as both parties prepare for the final six-week campaign push after the summer lull, any attempts to breath new life into the moribund party seem to have failed.

So what lost Schulz his spring advantage?

The SPD leader and others have argued that Germany is Europe’s dragon, sitting on a pile of gold which isn’t put to work. Schulz proposes that the treasure be used to boost public services and reduce unemployment. He also wants to roll back the stringent, though successful, Hartz reforms and institute a new wealth tax on those earning above 250,000 euros to fund it.

However, to a majority of the notoriously pragmatic German electorate, this rings very hollow. Merkel’s economic policies have worked wonders for Germany; by exports, they are Europe’s most successful nation. Many feel a quiet sense of national pride at this fact, and dislike Schulz’s dismissive tone towards their economic success. If it works, why change it? Nor has his presidency of the European Parliament much helped. A man who has for so long been on the Brussels gravy train can’t be taken seriously when he challenges Germany’s economic success.

Schulz also sounded the wrong note when he spoke out against American pressure for countries to meet the 2 per cent Nato defence spending target. Germany has a strange relationship with its military; its population are understandably pacifistic. Rarely deployed overseas, the Bundeswehr is still only usually tasked with domestic defence and UN peacekeeping missions.

However, Ursula von der Leyen, Germany’s minister for defence, has proposed radical reforms to the German army and an expansion of its international engagements. Given Germany’s growing diplomatic roles in both Europe and on the world stage, an expanded military capability would make a great deal of sense.

Schulz has labelled this ambition Geschichtsvergessenheit – a common German term, inferring a forgetfulness of Germany’s Nazi history. It’s a distastefully myopic attitude. Germany has a serious role to play on the Continent and needs to put itself forward in the area of European defence. Now the Franco-German axis on which the EU rests has been given a kickstart by Emmanuel Macron, it seems impossibly naïve to declare that Germany should not make more progress vis-à-vis reform and expansion within its army.

Schulz, in brief, is the wrong answer to a limited set of national questions. Germans want to see continued economic and diplomatic success, both of which are continually delivered by Merkel and the CDU.

The SPD’s candidate is an unimaginative Eurocrat whose milquetoast proposals inspire little confidence. His tepid and hesitant foreign policy proposals would only take Germany backwards; his economic policies would see little change in a eurozone still reeling from a saga of debt crises and currency wobbles. Germany’s voters know this.

For as long as Germany is economically and politically strong, there will be no drama and there will be no change: Merkel will remain chancellor.