The narrative that it is only a matter of time before student tuition fees are abolished is beginning to take hold. Once the preserve of the Radical Left, it is a view that is becoming increasingly mainstream. The arch Blairite Andrew Adonis recently said that “fees have now become so politically diseased, they should be abolished entirely”. And even Government Ministers are wobbly on the issue. Damian Green, Britain’s new First Secretary of State, has called for a “national debate” on the subject.

But what would we want this “national debate” to look like?

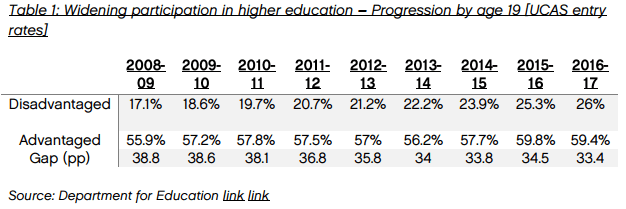

As it stands, the system seems to be working. It is, for example, now widely accepted that more disadvantaged youngsters are going to university; data released yesterday showed that the size of their cohort has increased by 4.8 percentage points since the £9,000 cap on fees was introduced. Jeremy Corbyn was rightly castigated when he falsely claimed earlier this year that the size of the fees meant that fewer students from working class communities were now going to university.

Much is made of the financial burden that is placed on students, who will, on average, have accumulated over £40,000 of debt by the time they graduate. But the debt is effectively risk-free and taxpayer-backed; a large number of graduates (35-40 per cent) will have much of their debt written off by the taxpayer after 30 years. In fact, the Institute for Fiscal Studies estimates that for each £1 loaned to cover the costs of tuition and maintenance, the long-run cost to the government is 43.4p. This means that the average loan subsidy per student from the taxpayer amounts to £17,000, with the lion’s share going to the lowest earning graduates.

In return, the whole country benefits when a youngster graduates, through the promotion of higher economic growth rates. And there is also an indisputable financial benefit to the individual. University graduates, on average, earn £9,500 more a year than non-graduates, rising to a £15,500 per year premium for postgraduates.

The existing system, therefore, strikes a balance between the responsibilities placed on the individual and those placed on the taxpayer. Yet Jeremy Corbyn is proposing to shift the burden of higher education costs almost wholly onto the taxpayer. This is a regressive policy in three key ways:

1) It is a subsidy from the less wealthy to the more wealthy, and the impact on the taxpayer would be significant. The money Labour planned to spend on repealing university tuition fees and introducing maintenance grants is the equivalent of nearly 2.8 percentage points on the basic rate of income tax.

2) While there has been some dispute about Corbyn’s pledge on existing student debt, his initial promise to “deal with” it (now watered down to an “ambition”) implied that resources would be used to alleviate those debts. This, again, would be an additional taxpayer subsidy that would involve transferring resources from less wealthy non-graduates to more prosperous graduates.

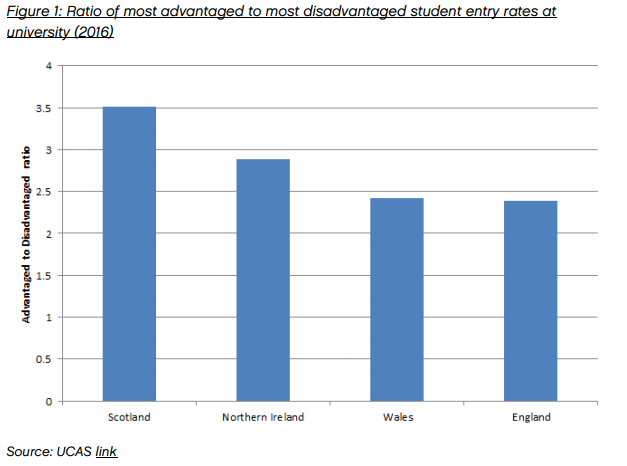

3) In Scotland, where there are no tuition fees, a lower proportion of disadvantaged students go to university. The ratio of advantaged to disadvantaged entry rates stands at 3.5, while in England, it is 2.4. This is partly because the Scottish Government capped the number of places allocated to Scottish and EU students which means fewer opportunities to attend university. If fees were to be abolished in England, this could lead to a rationing of university places and have a detrimental impact on the participation of disadvantaged youngsters in Higher Education.

None of this is to say the tuition fees system is perfect. The cap has meant that price competition, as envisaged by the Browne Review, has not come about. Retrospective measures have effectively hiked repayments for students, and the interest rates on loans are seen by many as excessive. These are certainly areas that could form part of a national discussion on this issue.

However, abandoning tuition fees altogether, as proposed by Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour Party, would be hugely irresponsible. Such a policy would act as a subsidy from comparatively less wealthy non-graduates to graduates, and would be implemented at a time when the UK Government is still living well beyond its means.

There is, of course, a need to redress intergenerational unfairness – the perception of which significantly affected the general election result. But the abolition of tuition fees would simply redistribute resources between non-graduates and graduates. It would do little to tackle intergenerational issues.

The most effective and fiscally responsible way of addressing the problem would be to promote a radical housing policy and pursue more equitable welfare reform between the older and younger generations. The current Government should spend more time focusing on this, rather than appeasing Jeremy Corbyn and his irresponsible and unfair proposals on tuition fees.

“Wealthy Graduates: The Winners from Corbyn’s Tuition Fees Plan” by Daniel Mahoney is published by the Centre for Policy Studies