When Philip Hammond stands up to deliver the Autumn Statement, almost all of the attention – if the past is any guide – will be on how he decides to spend the nation’s money.

But it’s time that the Chancellor, and the country, took a much closer look at the other half of the equation: namely, how he collects it.

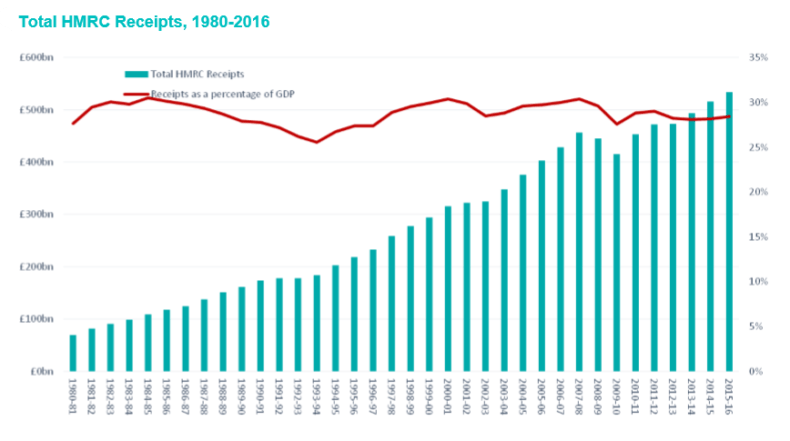

HMRC has, over the past few decades, collected approximately 30 per cent of national income in taxation every year, or just under. (The country’s appalling fiscal position derives from the fact that successive governments have chosen to treat this as a floor for spending rather than a ceiling.)

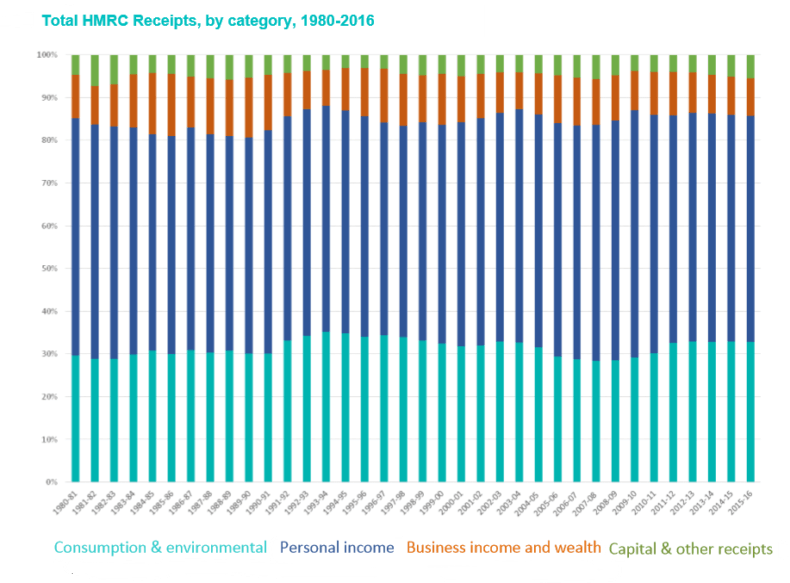

The vast bulk of that comes from the “big three” taxes: income tax, National Insurance (which is effectively income tax by another name), and VAT.

In 2015-6, for example, combined revenue from these three was expected to be £169.8 billion in income tax, £114.9 billion in NI and £115.8 billion in VAT – which comes to 63.5 per cent of the total tax take of £630.5 billion.

This dominance of the tax scene isn’t just entrenched, but increasing as other revenues dwindle. Corporation tax, for example, has been falling since about 1990 as a percentage of GDP, as successive governments cut it back in order to remain internationally competitive; the North Sea is no longer a cash cow; and drinkers and smokers are either giving up or dying off, cutting the take from sin taxes.

This might sound quite technical, but it has really big implications – most of which damage the economy, in ways large and small.

First and most obviously, it makes the public finances much more dependent on the state of the economy. When times are tough, fewer people are getting jobs, or pay rises – and fewer people are going shopping. That means that variable taxes – as opposed to fixed levies like business rates, council tax or TV licences – suddenly slump.

Conversely, during boom times the high receipts can lead chancellors into a state of irrational exuberance, in which they assume (as Gordon Brown did) that the bumper receipts are structural, not cyclical, and embark on an ultimately unaffordable spending spree.

The next problem is that, under this system, the great bulk of the heavy lifting is done by ever fewer people.

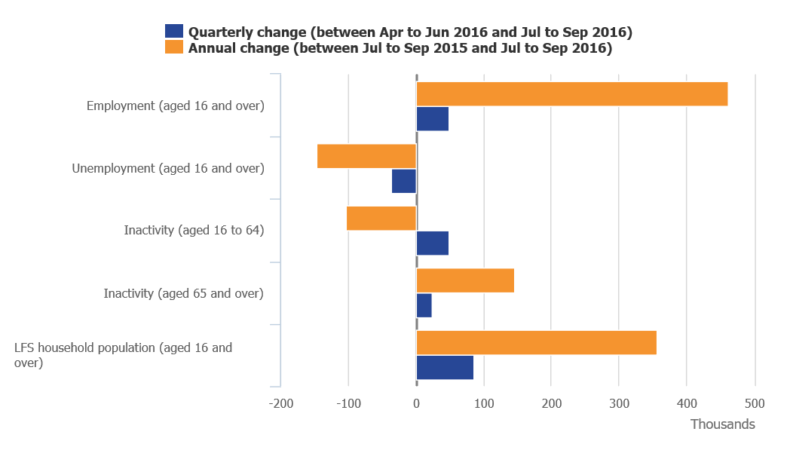

The UK economy is really good at creating jobs. For example, there are now almost half a million more people in employment than there were this time last year.

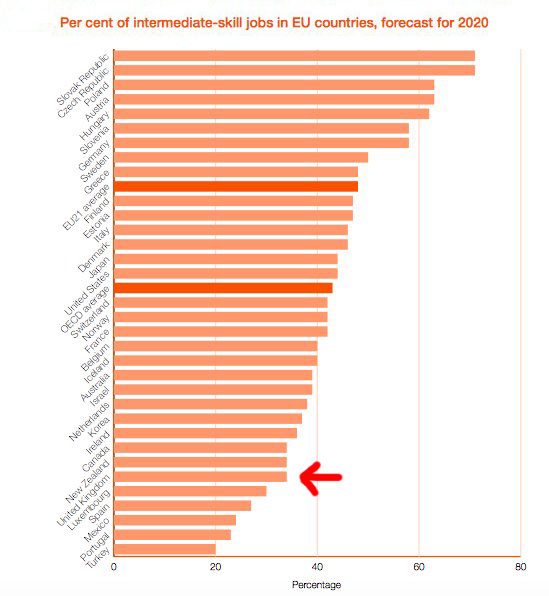

But we’re much less good at creating high-paying jobs. The UK’s flexible labour market means it’s easy to find low-wage employment (which can, in turn, be a first rung on the economic ladder). But as the latest report from the Social Mobility Commission shows, we’re lagging behind the rest of the developed world when it comes to creating more skilled positions:

At the same time, the Coalition’s decision to take an increasing low-paid out of tax altogether – a Tory manifesto commitment which the May government is likely to stick to – means that many of the people getting those low-paid jobs aren’t actually contributing (or rather contributing directly) to the government’s coffers.

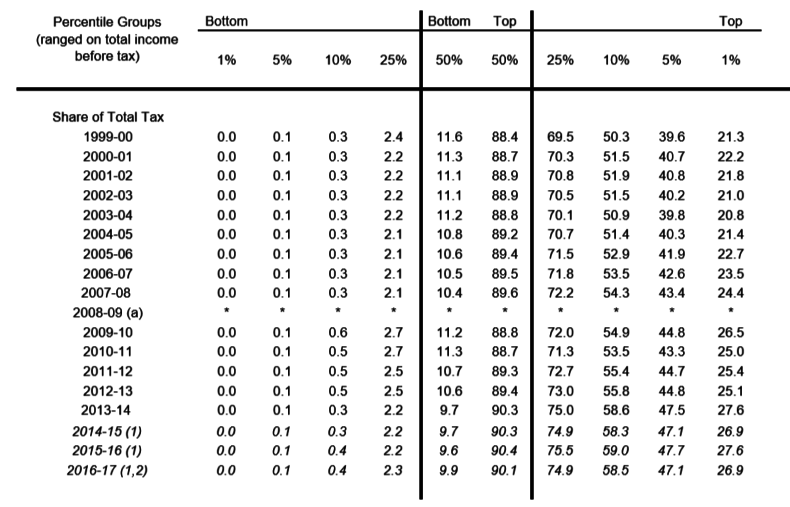

This, in turn, means that the burden of paying the government’s bills falls squarely on those higher up the income ladder.

According to the latest Treasury figures, the bottom half of the workforce (in salary terms) pay less than 10 per cent of the tax. This chart from HMRC shows how the tax burden has steadily, inexorably, been shifted on to fewer and fewer shoulders:

Or, to put it another way, there are fewer than 50,000 people in this country, out of a population of more than 64 million and a taxpaying population of some 30 million, who earn more than £500,000 a year. And they’re paying £22 billion in income tax between them.

That’s 0.08 per cent of the population paying roughly 13 per cent of the income tax (not counting their other contributions to the economy).

My goal in pointing this out isn’t to argue that these people are over- or under-taxed – they certainly pay far more than their share, but then they’re left with a lot more at the end of it.

It’s to point out how vulnerable this makes the whole tax system to a few defections.

If a couple of hedge funds decide to move to Zurich, or a large City firm decides to switch operations to Dublin, the government’s income will tax a disproportionate knock.

Under the worst-case scenario, in which there’s a mass flight from the City, the Government is left having to pay the bills for millions of people in terms of public services, welfare etc – without the golden geese who have made the whole system possible.

But there’s another big flaw in this system of taxation, with its heavy emphasis on milking workers of their income. And that’s the way it discriminates between generations.

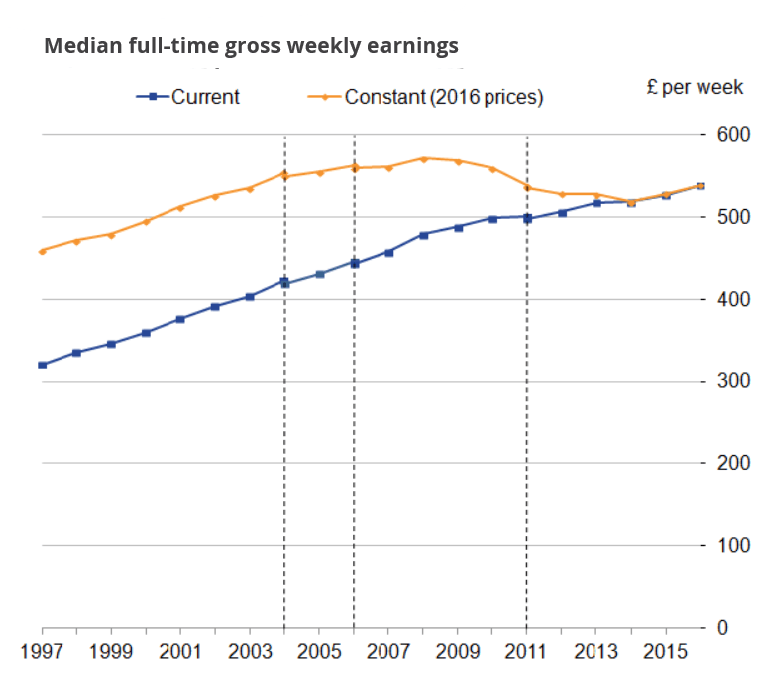

Britain is now in the surreal situation where pensioners are earning more than workers. As this ONS chart shows, average salaries for workers, in real terms, are at roughly the level they were in 2011 – and 2003. Yet pensions have kept on rising.

Obviously, we want to ensure that people can enjoy a comfortable old age. But we’ve reached a surreal – and wrong-headed – situation where the people who are actually working, day in, day out, are making less from their labours than those who are enjoying the fruits of their labours in decades past.

Those aged 65-74 now have a greater share of UK wealth, claims the Resolution Foundation, than those aged under 45.

There are all sorts of reasons for this: the Government’s “triple lock” guarantee, years of rising house prices, the natural consequences of having paid off your mortgage and having a decent pension portfolio.

But it’s also down to – yes – the tax system.

This chart from the Treasury shows the balance between the different kinds of taxes that the government takes in:

As is immediately apparent, those on income (the dark blue segment) are vast – and those on capital (bright green) are tiny.

I don’t want to come over all Thomas Piketty here: I’m well aware of the case against double taxation (ie that if you’ve already had your income taxed, why should the government have the right to tax what you buy with it?).

But what Philip Hammond is lumbered with is a tax system which asks workers to pay for pensioners – even when those pensioners, in many cases, have substantially higher assets, substantially higher incomes and a substantially higher quality of life.

And the same system, at the same time, asks a shrinking number of those workers at the top of the pay scale to pay ever larger amounts to cover all the rest of us.

Today, when the Chancellor stands up, I don’t expect him to do too much to change this. It’s far easier to focus on the output rather than the input – how to fund infrastructure, the NHS, welfare and so on and so forth.

But at some point, we need to have a serious think about the fact that our taxation system has an ever narrower and ever less stable base.

Otherwise Mr Hammond, or his successors, could be in for a very rude awakening when it finally topples over.