Bruce Anderson is backing the Prime Minister David Cameron in his efforts to persuade the UK to stay in the EU. He explained why in a recent piece on CapX. Anderson’s friend, Lord Salisbury, a former Leader of the House of Lords, and a board member of CapX, disagrees forcefully and has published an open letter in reply to Anderson. Now Anderson responds.

Dear Robert,

There have been widespread complaints about the tone of the Referendum debates: too much anger and abuse, too little breadth of vision. But no-one could accuse either you or Niall Ferguson of lacking moral seriousness.

1) Britain and Europe: pre-history, gracious deliverance; history, two millennia of troubles.

Geography shapes history, culture and politics. Much the most important event in British history occurred hundreds of thousands of years ago when a giant convulsion created the English Channel. If that had not happened, British history would have been fundamentally different. From then on, we were protected from many of the ravages which afflicted the Continent. We had our moat, for which we should all give thanks. To invert St. Mark, what God hath pushed asunder let no man join together.

But Europe was still there, still intertwined with our history, especially under the Romans. Even those who enjoy counterfactual history might quail before the task of working out what have happened if the Romans had not conquered England. So it might be wiser to conclude that by anchoring us into continental civilisation, the Romans were a beneficent force. Our Roman heritage made it easier for us to emerge from the Dark Ages. Equally, those parts of the British Isles which were never ruled by the Romans are significantly less civilised and have found it hard to make a decisive break with the Dark Ages: in Scotland, increasingly hard.

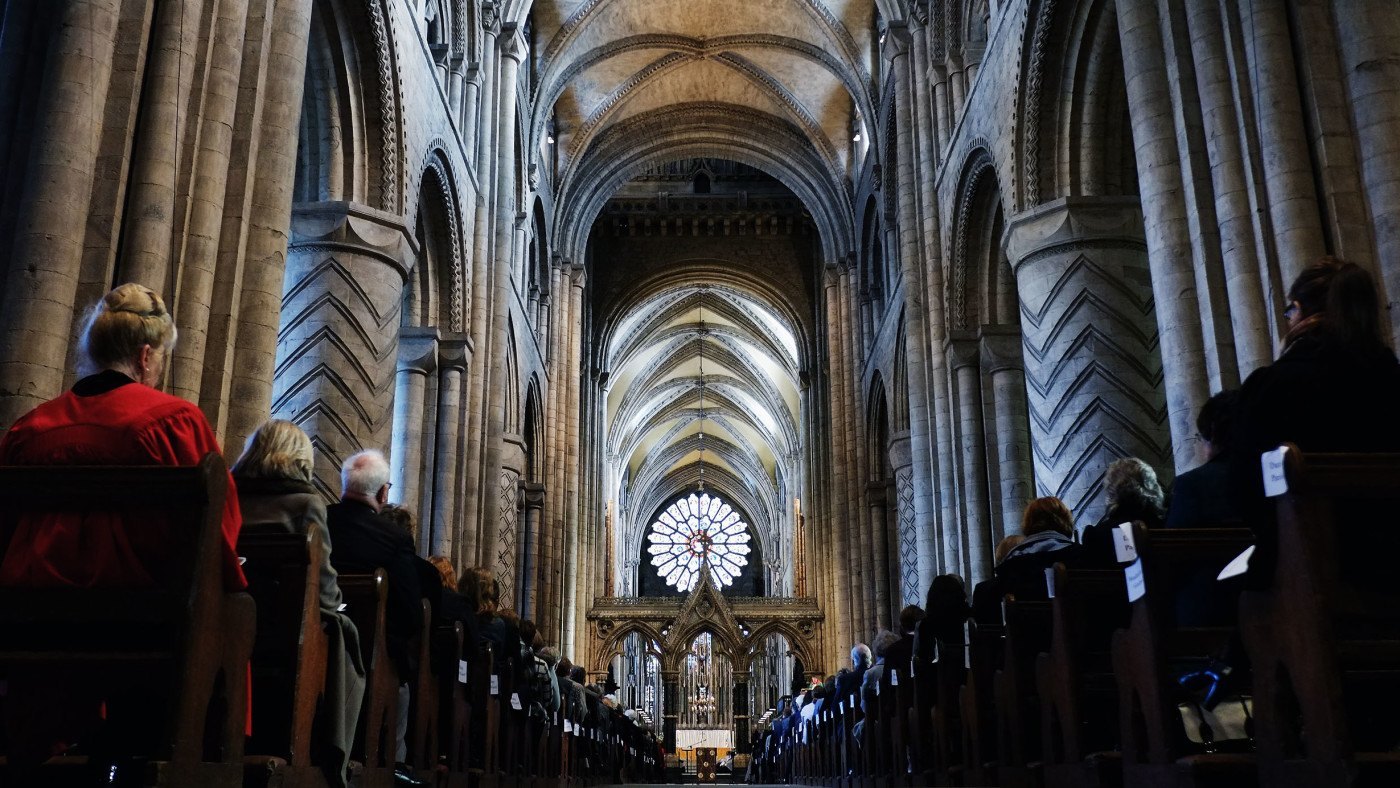

So what about the Normans? Sally Harvey, who knows as much about English history on both sides of 1066 as any scholar now active, has taken arms against the casual assumption that the Normans were a civilising force. She argues that Anglo-Saxon culture was developing rapidly and could have rivalled the glories of Norman architecture. Moreover, these civilised Normans waded through blood and cruelty to subjugate their foes. (Another ‘what if’; suppose that instead of hurrying his troops down from Stamford Brook, King Harold had taken his time to assemble a larger force, to deal with the Normans as they were swallowed up in the Kentish bocage?) Returning to Dr Harvey, is there not a two-word refutation: Durham Cathedral? Could the Anglo-Saxons really have equalled that? In awe at its glories, one finds it easy to forgive the savageries during the harrying of the North. Brutal to their victims, harsh to their villeins: when the Normans were in action, it was always a case of vae victis. But we can no longer hear the cries of the sufferers and the slain; they have been dust for almost a thousand years. The buildings endure, in beauty, grandeur and triumph. Durham and the other great cathedrals could be seen as a more than adequate lapidary penance.

The Norman Conquest also rescued England from the threat of other invaders: the Northmen of Scandinavia. Their Southern kin were preferable. Under them, instead of declining into a South Scandinavian kingdom, we became part of Romano-European civilisation, as we have always remained. Equally, under the Normans, England rapidly became a unitary state. In 1100, there were laws in Westminster Hall. By 1200, they were the laws of all England, to England’s abiding advantage. All in all, 1066 was a war worth losing.

That was not true of the Hundred Years War. The entire course of subsequent French history calls in question France’s worthiness to be a country, as opposed to a cuisine. If only we could have held on to the Western coastal regions of France from Gascony to Normandy, while Ducal Burgundy had become the fulcrum of a Middle Kingdom and the Capetiens/Bourbons were granted the rest – France and the world would be so much better off, with three different and complementary civilisations replacing one failed state. Joan of Arc deserved to be burnt.

Moving forward to Wolsey and Henry VIII, I would respectfully differ from you and Niall. Indeed, I would go further and accuse you both of anachronism. Niall would have us believe that Wolsey was the lost champion who could have encouraged Europe to resist the Turks. But if that was the Cardinal’s goal, he was guilty of naivete: a charge rarely levelled against him. Such a strategy would have required the cooperation of the French, who were less interested in forming a coalition with the Hapsburgs than in weakening Hapsburg power. Paris was much further away from the Turkish front line than Vienna was.

You see Henry VIII as a pioneering Euro-sceptic, breaking from Rome and Wolsey to assert English independence. I place a much lower, more carnal, interpretation on events. Henry wanted a male heir and had identified a toothsome wench to provide one. Poor Anne Boleyn: a daughter, a miscarriage: a skilled swordsman from France. Even across centuries with plenty of bloodstains, her tragedy is plangent: from Coronation to execution in just under three years. Her last letter to Henry, in which she asserts dignity to hold fear at bay, can still moisten an eye.

It is true that the King’s Great Matter changed the course of everything. It set in motion events which led to individual freedom, the rule of law and a relatively peaceful constitutional history, leading to Enoch Powell’s favourite mystification. The Crown in Parliament. But this was a concatenation of unintended consequences. It owed nothing to any conscious decision on Henry’s part; far more to an Italian battlefield. The battle of Pavia, 1525, is up there with 1066 and 1940 as one of the crucial dates in English history. Suppose it had gone differently? If Francis I had won, he would have been master of central Italy and there would have been no reason for the Pope to deny Henry VIII his divorce. As it was, Charles V prevailed and objected to the mistreatment of his Aunt, Catherine of Aragon. So Henry had to break with Rome in pursuit of a girl, and a boy.

Again, we are back in the fascinations of what if. There is no evidence that Henry VIII was drawn towards Protestantism. His theological interests were fitful, on a Boris Johnson scale, and primarily concerned with vainglory: the comparison persists. Although there would have been religious trouble, that is no reason to assume that the troublemakers would have prevailed. Eamon Duffy, surely the most important current historian of England, has reinterpreted English religious history after 1530. Because of his efforts, the A.G.Dickens of our youth seems vieux jeu, while we have all been made aware that the English reformation was a damned near-run thing. If the Pilgrimage of Grace had been led by a ruthless commander, Henry might have lost. But Henry VIII was neither the first Euro-phobe nor the first Whig. As for his religious settlement, we have to turn to another Irishman for a succinct and incontrovertible summary. In Brendan Behan’s words, ‘The Church of England was founded on the bollocks of Henry VIII.’

Physical separation from Europe saved us from the extremities of religious conflict though not, alas, from domestic iconoclasts. If only the reformers could have treated the rest of the cultural heritage of Catholicism in the way that Archbishop Parker treated its manuscripts. But this is the way a fallen world works. To the men of that era, religion was more than a sub-set of aesthetics.

The Channel also spared us from the ravages of the Thirty Years War. Our own Civil War was much less destructive. Apropos of Boris Johnson, we can all be grateful that the reigning Cecil of that era was a slippery and opportunistic character, who was careful never to be on the wrong side at the wrong time. Indeed, the parallel with Boris is unfair. When it comes to ambition, Boris is all bumbling and bluster. Subtle and sophisticated, that Cecil concealed his goals in silken reserve – so posterity should salute him. If he had been inclined to romanticism in politics and to leaps in the dark, he would have supported Charles 1 through thick and thin…through thinner and thinnest. Hatfield would no doubt have been fortified, but it was far too near London to be defensible. In one of the earlier engagements, as the Royalist cause began to founder, it would have been battered into ruin and submission by Parliamentary cannon. For its four hundredth anniversary, instead of graciously understated pomp and circumstance, a few bits of masonry might still have been visible above ground, of interest only to archaeologists and English Heritage. The Channel and the opportunities it offers works best when supplemented by native cunning.

Skipping forward until the French revolutionary wars, I do not believe that Niall and Robert are that far apart. Unless we had been prepared to save ourselves by our exertions and Europe by our example, Bonaparte could not have been defeated. But that makes an enduring point. Even if we turn our back on Europe, it is still there.

When it came to warfare, the French revolutionaries bequeathed mankind an evil endowment. In effect, they split the atom. The levee en masse released unprecedented amounts of energy. It may be that the early Mohammedans and Genghis Khan achieved something similar, but those were transient barbarian frenzies. Industrialism and mass mobilisation combined to ensure that the wars of peoples were indeed far more terrible that the wars of kings.

Again, it was impossible for us to cut ourselves off. Niall has made a powerful case that we should have stayed out of the First World War. But had we done so, the Germans would have won and dominated the continent. Having abandoned our allies, we would have searched in vain for new friends in Europe – while America, still observing distant events across thousands of miles of ocean, might have seen little reason to intervene in Europe, or to quarrel with its new German masters. The tragedy was 1888 and the death of Kaiser Frederick II aged only 59. He was a constitutionalist, a liberal and an Anglophile. During the Franco-Prussian War, he had commanded an army. So his natural abilities were supplemented by prestige won on the battlefield and confirmed in the council chamber. To paraphrase Tacitus: everyone agreed that he could have made a great Kaiser – if only he had been given the chance.

It would not have been easy. In the early Twentieth Century, there was a potentially lethal combination: lots of geo-political tinder and an almost total insouciance about the consequences of war. But Kaiser Frederick might have had the wisdom and the judgment to negotiate a way through. After all, when it comes to war, generals are usually far more cautious and realistic than politicians. It was not to be. Instead, we had Kaiser Sarkozy: the First World War, the Second Fall of Man.

It also made a Second World War inevitable. Robert is right, in that there was one chance to prevent it: block Hitler’s reoccupation of the Rhineland. But by 1936, almost everyone in Europe – including the Rhinelanders – thought that the Germans were justified. There is a tragic irony. In the early Twenties, the Allies were too hard on the Germans, sabotaging German liberals’ attempts at consolidation. By the mid-Thirties, after a guilty conscience had weakened Allied resolve, there was nothing to undermine Hitler’s consolidation.

Appeasement was neither fatuous nor ignoble. If we had gone to war at Munich, how much practical help could the Russians have provided? They had a very small land frontier with Germany, and Stalin had been preparing for conflict by slaughtering his officer class. How staunchly would the Czechs have defended their homeland? What about that second volume of the Good Soldier Schweik, in which the hero rises the rank of Field Marshal in the Czech army? Above all, could we have fought and won the Battle of Britain in 1939?

But appeasement failed. Once again, we were at war in Europe. Once again, the Channel saved us. In 1945, Europeans were determined to ensure that this really would be the war to end all wars. Out of defeat and destruction, they wrested an ideal – which we could not share. By 1945, any thoughtful Brit might well have decided that there was an obvious lesson from history. To us, the threat came from attempts to build a European superstate. Philip 11, Louis X1V, Napoleon, now Hitler: those were the enemy. Nation state: our beloved nation state, King and Country? That is what we had been fighting for. So now it was back home to Blighty, take your boots off, have a cup of tea, not to mention stronger liquors, in front of a good fire (if you could find any coal) – and forget about the foreigners for a bit.

Some of the foreigners had other ideas.

2) Europe: triumphs and miseries.

The Coronation of Charlemagne marked the end of the Dark Ages. Within a few decades, as his Empire was divided, a Middle Kingdom was established, Lotharingia. What a romantic name and idea: a realm with a chivalric court, embracing the valley of the Rhine, which could harmonise the Franks and the Teutons in a new Roman Empire; a great river, as the conduit for commerce and civilisation. Later, perhaps, Lotharingia could have merged with the Sicily of the Angevins and Hohenstaufens, to create a middle kingdom that would also be the mistress of the middle sea.

As always in human affairs, original sin prevailed. There was no harmonistion. For centuries, the conduit became a frontier and a battlefield. It is surprising how much survived the ravages of war and conquest. Then came the wars of the peoples. It is important to remember that for much of the Nineteenth Century, European nationalism appeared to be a fruit of the Enlightenment: a means of enhancing the lives of the peoples. In the Twentieth Century, as those peoples were conscripted into armies mobilising the destructive powers of modern technology to the devastation of old Europe, it became clear that nationalism came in jackboots. Humankind cannot bear very much Enlightenment.

As late as 1900, on the reasonable assumption that the United States was a mere daughter house, Europe ruled the world. Its banks and its bourses, its armies, navies, chancelleries and colonial offices: thus were the world’s affairs regulated. But in August 1914, the second dark age began. By 1945, forget the gentle idealists of the Enlightenment; Ezra Pound and Nietzsche appeared to be right. Europe did indeed resemble an old bitch gone in the teeth. It had stared into the abyss and the abyss was now staring back. There was every reason to believe that Europe had destroyed itself to create a playing field for a third and final world war.

The idealists led the slow crawl back from the abyss. Nationalism had failed. So some of the finest young minds in Europe concluded that the only hope of survival was in supra-nationalism. Thus the seeds of the EU were planted in scorched earth surrounded by rubble. They bloomed beyond reasonable expectations, and – once again as always in human affairs – apparent success merely bred a new set of problems. The EU helped to rebuild Europe. In so doing it rehabilitated the nation state. Nations need not always be a threat to their neighbours and themselves. Those who will not learn from history are condemned to relive it. By 1945, at extinction point, Europe learned from history. Nations can change. After all, in 1648 it seemed impossible to co-exist peacefully with the Spaniards. In 1815, the same was true of the French. By 1900, a lot of Europeans thought that we British could be pretty insufferable. By 1945, it was the Germans. It is not always clear that the Germans have changed as much as they should. Although they insist that they are penitent, they are still far too keen on bossing their neighbours about. It sometimes seems as if the old cautionary adage should not be entirely discarded and that the Hun is either at your feet or at your throat. Yet at the very least, there has been an improvement. Bossy-boots are preferable to jackboots. With the Hun, that may be as good as it gets. But it is tolerable.

The bossy-boots version of the Hun problem has emerged because the EU has had many successes. It is now inconceivable that France and Germany could go back to war over Alsace-Lorraine. The nations of the Soviet Empire seemed happy to join the European order, and its attractions were obvious. For more than fifty years, the European economy flourished. Then the problems began. In 1945, it seemed easy to argue that the nation state was a lethal obsolescence. But after half a century of recovery, that case was harder to make. War had taught Europeans to live in peace. One symptom of peace is to feel at home in one’s own country with its own political system, making laws and protecting liberties. If you grow excessively exasperated with your politicians, you will have a chance to turn them out. That would not be true in a European Union which lived up to its name.

Helmut Kohl wanted to achieve political union while the war-guilt generation was still alive. That is why he pressed ahead with the single currency, even if it meant working on the roof before the rest of the house was built. The French political elite had accustomed itself to the sonorities of ever-closer union, and was still able to deceive itself that Europe meant a French jockey on a German horse. With the euro-zone, the time for sonority was over. Monetary union was impossible unless fiscal union followed, with fiscal transfers. In turn, that would require political union. But would the voters of Munich really accept the need to subsidise Messina? In Aachen, would they be happy to pay for Athens? The French have already lost their currency. They are rapidly losing their language. (There is an irony: the common European language policy is working, but the winning language is English.) Would they really be happy to lose their sovereignty: to become a Texas or a Western Australia – a powerful unit within a federation, but ultimately a subordinate one?

At the moment when Kohl and Mitterrand pushed the EU into a currency crisis, it also faced a competition crisis. The economies of Europe were menaced by bureaucracy and regulation. These two crises resulted in mass unemployment, in countries with no deep roots in political or social stability. During the first Dark Age, Europe lost its primacty to the Indians and the Chinese, who were too far away to matter, and to the Muslims, who did matter and sometimes looked as if they might prevail. Now, primacy is gone again, never to be regained. At a time when the world desperately needs the best of old European values – as does Europe itself – the continent is too weakened, too lacking in confidence, too racked on a monetary Procrustean bed – to be able to defend itself, let alone rescue others. Europe appears to have lost both the means and the will to power, world without end.

Between 1517 and 1700 (later in some places) wherever Protestants and Catholics came in contact, they came in conflict. Almost all the wars had a confessional dimension. Peace, when it did prevail, largely depended on exhaustion. Today, there is a similar upheaval in the Islamic world. What, if anything, will bring peace? In its absence, how can nuclear terrorism be prevented?

3. Britain and Europe now

Incompatibilty: geograhical, historical, political. There would seem to be only one conclusion; rush for the Brexit. On the contrary, that would risk the danger of precipitating a crush. If we could cut ourselves off from Europe as anything more than a tourist destination, there would be a powerful case for leaving. Equally, if everyone was flourishing, with no threat from the Middle East and no problems with Russia, why not renegotiate a looser membership on old-fashioned EFTA or Hanseatic League terms?

None of that applies. What will the Middle East be doing in six months time? What about Turkey? What are the prospects for political stability in China? What is Putin up to? Not long ago, everyone was talking about the Brics. Now, some of them seem to have turned into straw. And what price President Trump? Not since the late Thirties have global affairs looked so volatile, so unstable, so threatening. There is one obvious conclusion. This is no time to take risks. If we left the EU, much of the serious world would lose confidence in us. This would inflict long-term damage on our economic hopes. On the continent, there would be abiding resentments (it must be rememembered that a lot of them blame us for the banking crisis, and from messing up the Middle East). The problem about stressing all the dangers is that it can sound as if one is belittling one’s own country. But caution does not equal belittlement. Plenty of sophisticated Americans are now horrified about the thought of Donald Duck in the White House. This does not mean that they are running down their country. Not only can a realist be a patriot. Any worthwhile patriot must be a realist.

Has anyone identified one single respect in which the UK would be indubitably better off if we left the EU? In the great Falkland’s words, when it is not necessary to change, it is necessary not to change. As regards the UK and the EU, a Brexit change now would not only be unnecessary. It would be profoundly destabilising.

4. An afterword on loyalty.

You tease me for showing a Leninist loyalty to the Prime Minister. To me, the ‘loyalty’ charge is no reason for embarrassment. It is a compliment. I would also add tu quoque. From 1994 until 1997, when John Major was doing everything possible to save his Party and his government, he had no more loyal adjutant than you. That noble endeavour was ultimately doomed. It would be a tragedy if another valiant Premiership were to founder in similar circumstances.

This has been a good government. It not only steered us out of the great recession. It has addressed long-term structural problems which even her late Ladyship side-stepped. Although the benefits arising from the changes to education and welfare will take years to manifest themselves fully, there will be a significant contribution to national welfare. The same is true of many of the public sector reforms. Often, the cuts will lead to improvements.

Moreover, and this is a question any wise Tory should ask when contemplating change, what is the alternative? If David Cameron fell, could we be sure that there is no danger of Borisconi: of Boris Trump?

I think of myself not as a Leninist but as a liberal Hegelian. In politics, as opposed to the arts or athletics, Tories should always be wary of perfectionism; even of the search for perfectionism. That is only attainable in a better world, should one exist. On this planet, it is more a matter of common sense; of three steps forward, two steps back (that does sound a bit Leninist) and trying to ensure that the arithmetical balance remains that way round. With a few honourable if misguided exceptions, the Brexiteers seem to have discarded arithmetic and common sense, in order to act as cultists led by a clown. That is not how Tories should behave.