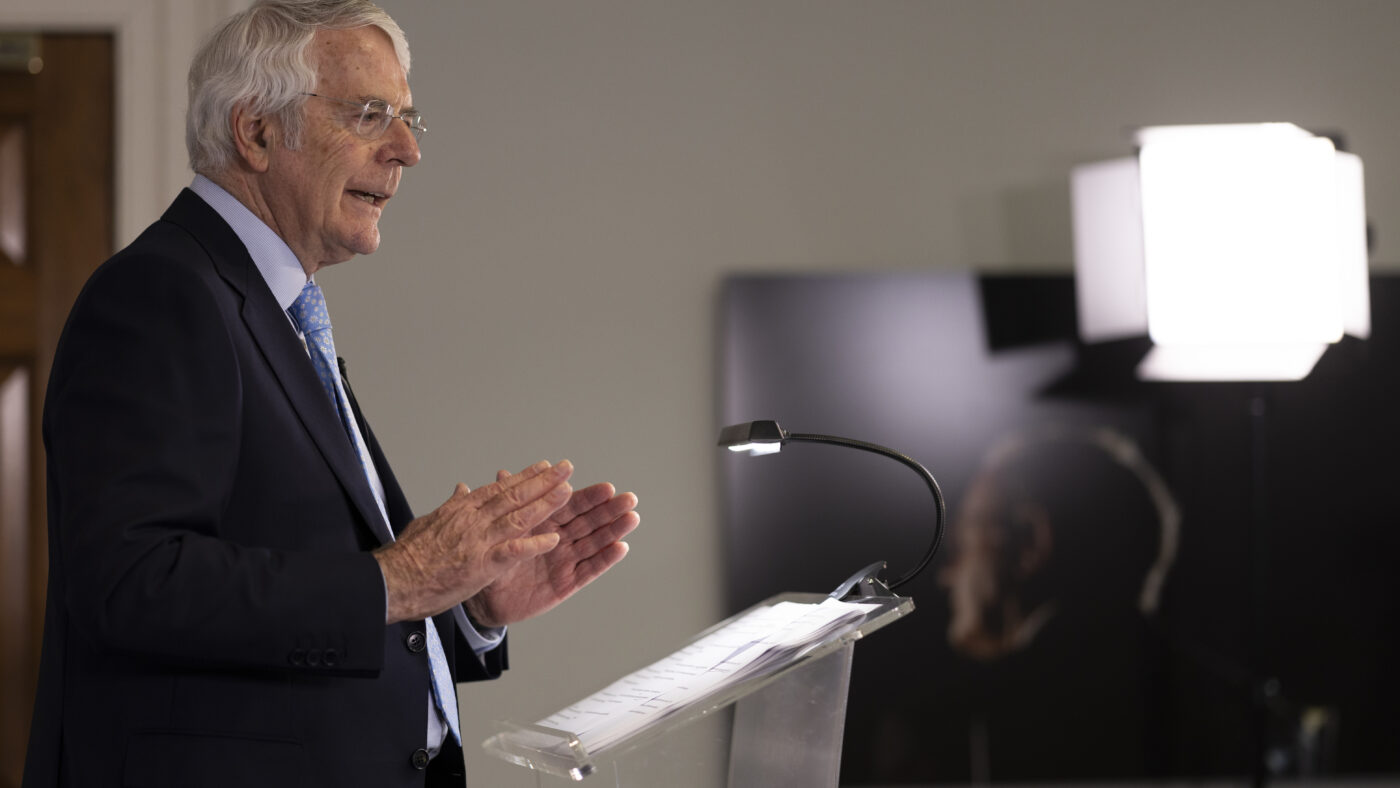

‘Prison doesn’t work’, to paraphrase the speech given by Sir John Major at the Old Bailey this week. This will be news to his former Home Secretary, Michael Howard, who memorably said the opposite back in the 1990s. So who’s right?

Neither of them, as it happens.

For starters, though, I need to give Sir John a bit more credit. He’s no prison abolitionist – a consequence, I’m sure of being brought up and educated in life well away from the cloistered abstractions of middle-class criminologists. He did, however, call once again for the abolition of short prison sentences, which clearly do nothing to rehabilitate offenders.

But short sentences aren’t the problem here. Across Europe the average custodial sentence length is 8.2 months and falling; in the UK that figure is 22.6 months and rising. In countries like Norway, reconviction rates for those released after 12 months inside is around 20%; in the UK the figure is 54.9%.

We outperform almost every EU country in this dismal achievement. We actually imprison people for longer, to less effect, than almost all of our continental peers.

The problem isn’t short sentences, it is that we do them so very badly. Many of those sentenced will be held for all of their sentences in teeming, brutalising local prisons where violence, indolence, poor staffing, drug addiction and mental illness make rehabilitation an exercise in wishful thinking. To make matters worse, because we are sending more people to prison for longer, plans to pull down some of the worst examples of Victorian squalor are on hold.

There are all sorts of cultural and scale reasons that make comparison with EU countries problematic, but as Sir John pointed out there’s nothing uniquely British about the propensity to offend more and more egregiously than our near neighbours. Indeed, in terms of rates of imprisonment, while we are above the EU median, prior to the skewing effect of the pandemic we were some way short of almost all the post-authoritarian EU accession countries.

Perhaps the problem of prison reform is just as much about the quality of the custodial experience as the quantity. This is not an argument favoured by many of our venerable prison reform institutions, who have been banging on about not banging up since the prison population was half the size it was today.

It also shines an uncomfortable light not on resources, as important as they are, but on the competence of the people running the system. Penal reform is a rather closed world, populated by a group of professionals, NGOs and academics who often shuttle seamlessly between these outlets in a hermetically sealed virtue bubble. There are alley cats as well as fat cats to be fair.

The Howard League’s fight to improve child custody by abolishing it fell on deaf ears, but it could never be said to be in the establishment’s pocket. Some of the smaller NGOs – in particular those working to get ex-offenders into employment after release – are lean and exciting examples of truly making a difference. But the remaining penal reform aristocracy is much more comfortable talking largely to itself, it has to be said, about the pains of imprisonment rather than practical ways to make it better.

Improving things would require some searching questions by former colleagues about how an organisation with over 5,000 HQ staff and legions of senior bureaucrats has let prisons fall into a state of such utter disrepair.

Don’t just take my word for it. Leaf through the majority of prison inspections – chance random visits that reveal an appalling picture of demotivated and overwhelmed staff, unable to release prisoners for more than an hour a day if they are lucky. Workshops are idle. Education is almost non-existent in some cases. Among the many scandals is that prisoners on Kafkaesque indeterminate sentences are literally being driven mad by not being able to access offending behaviour programmes that might reduce their risk to the public.

If we cannot get senior prison managers to work with governors to improve the quality of the time spent inside, then we need new senior management. No private enterprise would accept such failure, or buy the claims that it’s all down to a lack of resources. But accountability is a truth that dare not speak its name in a service that hides behind banal, often surreal press releases.

We need to be clear about a few things. The piety of ‘you go to prison is as punishment not for punishment’ makes for a lovely progressive soundbite, but falls apart on contact with reality. Our perverse prison economics – a higher cost per prisoner than Eton, for places where it’s sometimes easier to get crack than toilet roll – is dooming us to continued failure.

To borrow another hostage to fortune from the Major years, HMPPS needs to go back to basics. We need the abandonment of specious drivel about ‘rehabilitation culture’ and its replacement with a total focus on safety. Reforming prisoners can only stand a chance if it is delivered by suitable and sufficient numbers of well led frontline staff, clearly and confidently in charge. Unless prisons are places of safety and order, nothing else hopeful can take place – particularly in the core local facilities where many short sentences are served, which often do more to apprentice inmates to a life of crime than turn them into law-abiding citizens.

Prison does work in one important sense – it incapacitates offenders and punishes them for inflicting harm on others, or society more broadly. If we cannot resource the effort required to help them change their lives and stop making victims, we must clear the landings of people who aren’t violent and who need help, rather than punishment.

Yes, make community penalties better, as we’ve been trying and failing to do since I started off as a prison officer 30 years ago. But, as Sir John said, let’s also find ways of detaining and treating the addicted and mentally ill away from prisons that are almost designed to make them worse.

This was a wise speech in many respects. It did not resile from one of the key purposes of imprisonment that makes penal reformers squirm – retribution. But retribution alone, particularly in a system which simply will not cope with projected population figures, offends morality and is dumb politics. One of my lessons from working in prisons is simple: if you brutalise people, you turn out brutes. That’s a crime not only against the individual, but also his or her next victim.

We could do so much more for offenders with short sentences in a prison system with the time, space and safety to change lives. We should clear the landings of non-violent offenders to do so. Prison does work. Just not like this.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.